"The image is more than an idea. It is a vortex or cluster of fused ideas and is endowed with energy." -Ezra Pound

It's time for another Messier Monday, where we profile one of the 110 deep-sky objects that make up the Messier catalogue! This was the first large, accurate catalogue of fixed, non-transient objects to be assembled, and it makes for a delightful collection of targets for skywatchers all across the globe.

All throughout the next month, the Summer Triangle will delight skywatchers everywhere, as it flies high overhead in the early parts of the night. It contains a number of deep-sky objects, which you might expect, seeing as the plane of the galaxy passes through it. One of those objects is the very interesting and unusual globular cluster, and the subject of today's Messier Monday, Messier 71. Here's how to find it.

Image credit: Me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: Me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

The Summer Triangle is made of three very bright stars that far outshine anything else in their vicinity: Altair, Deneb and Vega. Just interior to the triangle by Altair, you'll see what looks like three or four stars (depending on the quality of your skies/vision) in-a-row, all easily visible to the naked eye.

Image credit: Me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: Me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

The two brightest of these stars are Gamma Sagittae and Delta Sagittae, and if you look directly between these two stars -- just a little bit closer to Gamma and a little bit "down" towards Altair, you'll find an unmistakeable collection of stars tightly clustered together: that's Messier 71.

Image credit: Me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: Me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

But what, exactly, is that cluster that you're seeing? Messier himself could barely see it:

[I]ts light is very faint & it contains no star; the least light makes it disappear.

Years later, William Herschel finally finally resolved it into stars, and now anyone with a good sky and either a reasonably large telescope or good astrophotography skills can see it for themselves.

Image credit: Jim Mazur's Astrophotography, from http://www.skyledge.net/.

Image credit: Jim Mazur's Astrophotography, from http://www.skyledge.net/.

It's very clearly a cluster of stars; the big question, though, that was hotly debated for nearly 200 years, was what kind of cluster it actually is.

You see, clusters of stars come in two different types: open star clusters, where typically thousands of stars form in a region a few light-years in diameter, and globular clusters, containing upwards of hundreds of thousands of stars in a region a hundred light-years in diameter or more. And then... then there's Messier 71.

Image credit: © 2005-2009 by Rainer Sparenberg, also J.Pöpsel, S.Binnewies, via http://www.airglow.de/.

Image credit: © 2005-2009 by Rainer Sparenberg, also J.Pöpsel, S.Binnewies, via http://www.airglow.de/.

This one was a nightmare to classify, seeming to be just on the border of the two types. Either it was a very large, very dense open star cluster, or it was a very small, very "loose" (or not dense towards the center), and -- perhaps most damningly -- very young globular cluster.

You see, globular clusters tend to be among the oldest objects in the Universe, with ages typically of 12 billion years or more, while it's very rare for an open star cluster to reach even one billion years of age. And then there's this one.

Image credit: © 2013 Louis P. Marchesi of Marchesi Observatory, http://astronomiae.com/.

Image credit: © 2013 Louis P. Marchesi of Marchesi Observatory, http://astronomiae.com/.

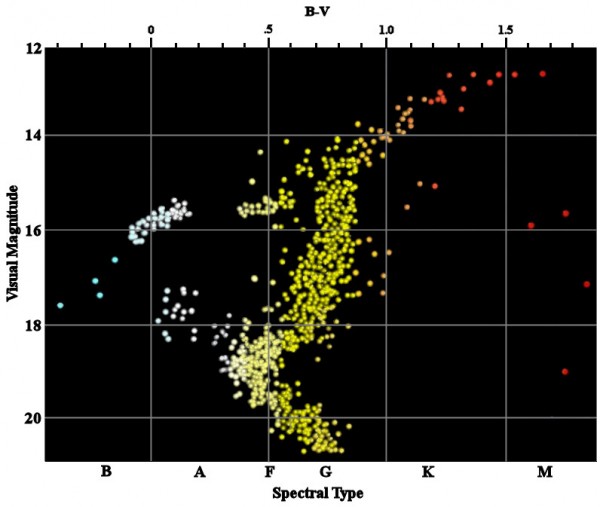

It's about 13,000 light years distant, 27 light years in diameter, contains about 17% of the heavy elements found in the Sun, and either it's an incredibly concentrated and large open star cluster, or it's an incredibly small, young, and diffuse globular cluster. The key discovery to settle the matter came in the 1970s, when a detailed photometric study looked for a special type of star: the horizontal branch stars.

As stars age, they run out of fuel in their core, and migrate up and to the right in the diagram, eventually becoming red giants (at the far, upper right). After that, however, as they age further, they migrate back towards the left, producing the "horizontal branch" seen at the mark of Spectral Type F and above magnitude +16 in the diagram, above.

And once that horizontal branch was found, we knew once-and-for-all what we were dealing with: a very, very unusual globular cluster!

Globular clusters are rated on a concentration class scale of I to XII; Messier 71 is one of the least concentrated ones known, coming in at class XI.

It was later determined that although the core of this cluster was only about 27 light-years in diameter, there are other members that are more diffuse extending out to a diameter of about 90 light-years.

Image credit: user Skipper of Astrobin, via http://www.astrobin.com/.

Image credit: user Skipper of Astrobin, via http://www.astrobin.com/.

This object was a real treat back in 2011, when Comet Garradd passed very close by to Messier 71, and a number of astrophotographers captured the brilliant cosmic coincidence.

Image credit: Emil Ivanov of http://www.emilivanov.com/.

Image credit: Emil Ivanov of http://www.emilivanov.com/.

Silhouetted against the backdrop of the Milky Way's plane, a deep exposure will bring out a plethora of stars; this is part of the reason why it took so long and why it was so difficult to determine M71's true extent. When a galactic background of stars (and foreground, as this object is 13,000 light years away) clouds your field of vision, it's very difficult to determine where the cluster actually ends!

Image credit: © 2006 - 2012 by Siegfried Kohlert of http://www.astroimages.de/.

Image credit: © 2006 - 2012 by Siegfried Kohlert of http://www.astroimages.de/.

Even in monochrome, this cluster is impressive if you can get sufficient magnification on it. With a mass of around 17,000 Suns and an age of between 9-and-10 billion years, it's a relatively small -- and somewhat newer -- globular cluster, but an interesting object in its own right nonetheless!

Image credit: user clasley of astrobin, via http://www.astrobin.com/users/clasley/.

Image credit: user clasley of astrobin, via http://www.astrobin.com/users/clasley/.

Of course, we're lucky enough to have a Hubble image of this object, too, and I'd never not show you that!

This view from Hubble is about 3.4 arc-minutes across, or just half the diameter of the core of this globular. As you can see, there are thousands of stars in there! Why not take a dive through the center of the original, high-resolution core with me? After all, there's no better way to finish off a Messier Monday than with one of these!

And that'll wrap up another Messier Monday! Including today’s entry, we’ve taken a look at the following Messier objects:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

Thanks to all of you who made it out to this weekend's star party, where we had exceptional, dark skies and fabulous views of the Moon, Saturn, Venus, and the Milky Way, in addition to the plethora of Messier objects and beyond! To those of you all over the world, here's hoping you get a chance to enjoy and experience the wonders of the night sky, and thanks for sharing this deep-sky object with me!