"I'm a man! I'm forty!" -Mike Gundy

'Twas the weekend before Christmas at Starts With A Bang, and the comments you left ranged from "hooray" to "dang!" There's much that you like and a bit you abhor, but some things require explaining some more. This past week saw seven posts, crafted with care:

- Did we just find dark matter? (for Ask Ethan),

- 25th Anniversary of Wendy's training music videos (for our Weekend Diversion),

- Our Universe changes (for Memory Monday),

- The Big Bang for children,

- Does the scientific method need revision? (by Sabine Hossenfelder),

- Quantum Immortality (by Paul Halpern), and

- Top 6 facts about the solstice (for Throwback Thursday).

And much that you said made me wish I was there. To teach you, and illuminate all that's bleak, so let's dive into your Comments of the Week!

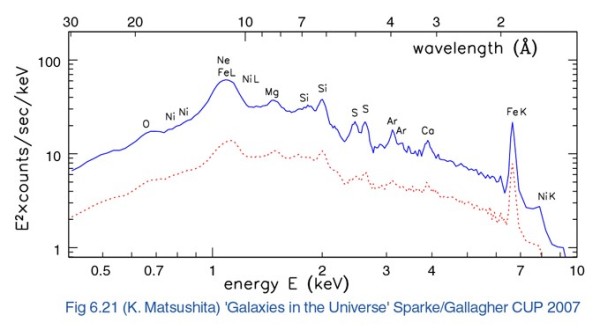

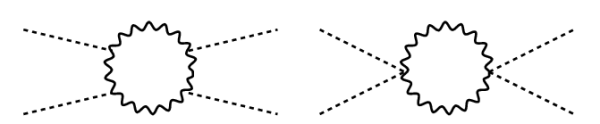

From jlnance on dark matter's signature: "Given that dark matter does not interact electromagnetically, why should it be assumed that annihilations of dark matter particles would produce photos, which are after all carriers of electromagnetic force?"

At the risk of sounding like a weasel, when physicists say "does not interact," we do not necessarily mean "the interaction probability or cross-section is zero." Which has got to drive you nuts, presumably, because that's kind of the definition when you make the statement "does not" anything, right?

So to be a little more precise, we mean:

- It does not interact in any way we've been able to measure.

- It has no theoretical basis for interacting, to the best of our understanding.

- We've been able to constrain its interaction cross-section -- experimentally and observationally -- to be far below the interactions of all known particles that do interact.

But all particles -- even, for example, neutrinos -- are thought to couple to all other particles through the power of quantum field theory, even if those interactions are tremendously suppressed.

Image credit: Rebecca Krall, Matthew Reece, Thomas Roxlo, JCAP 1409 (2014) 007, via https://inspirehep.net/record/1283753.

Image credit: Rebecca Krall, Matthew Reece, Thomas Roxlo, JCAP 1409 (2014) 007, via https://inspirehep.net/record/1283753.

Based on what we've observed from large-scale structure, we know that dark matter interacts gravitationally, and we know its strong, electromagnetic and weak interaction cross-sections are well-below the measured cross-sections for anything else that has a non-zero cross-section.

But if those cross-sections are truly zero, that begs two questions: how did these particles get produced in the first place, and how will we ever detect them? Because we assume there was some mechanism that produced them, we also assume there's some mechanism to detect them. Hence, we look for small but non-zero signs of those interactions.

Of course, the far more likely possibility is that this signal is due either to nuclear reactions/processes, astrophysical processes that don't require dark matter, or that it isn't a real signal altogether. But dark matter is a possibility, and so we look, we consider it, and we evaluate based on the evidence. It's possible, and that's what's worth keeping in mind.

From Skywriter on Carl Sagan: "Thank you Ethan for the Carl Sagan honor."

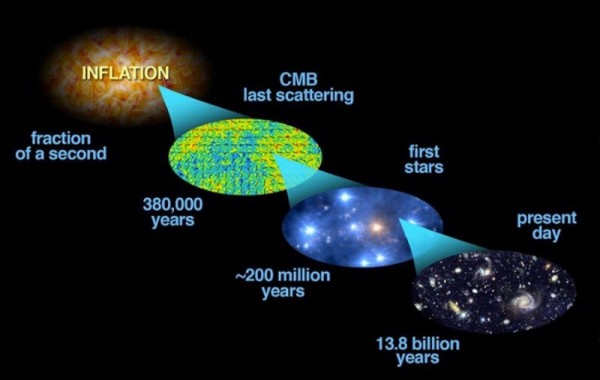

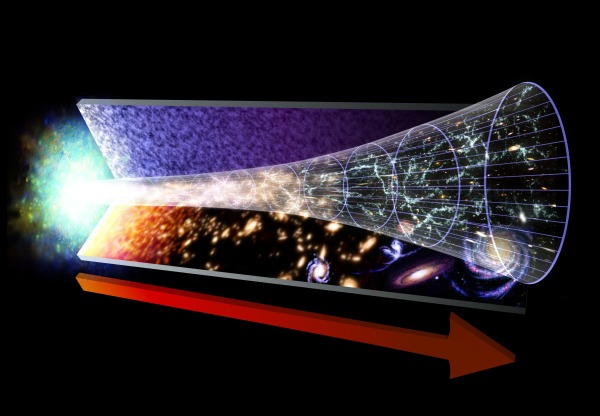

Although I'd like to take credit for this, all I did was give the talk that presented the biggest advances we've made in our understanding of the Universe -- where it came from, what it is today and where it's headed -- since Carl's original Cosmos was made a generation ago. The real thanks goes to the thousands of scientists who devoted their lives to making those scientific advancements and allowing us to put this updated, improved and more accurate version of the story together.

Image credit: NASA / GSFC, via http://cosmictimes.gsfc.nasa.gov/universemashup/archive/pages/big_bang….

Image credit: NASA / GSFC, via http://cosmictimes.gsfc.nasa.gov/universemashup/archive/pages/big_bang….

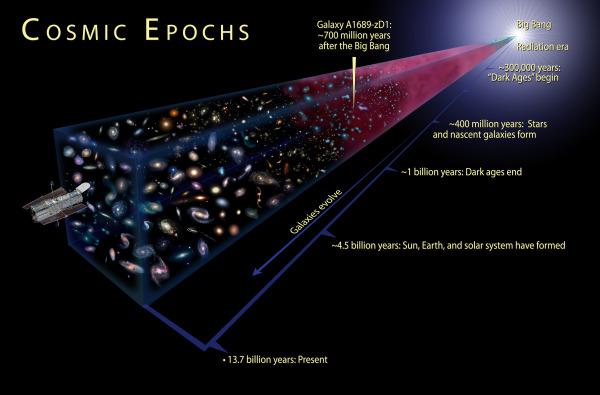

From Zed on the Big Bang for children: "Hmm, not sure how satisfying I find this metaphor. I think it introduces strange notions of agency and raises more questions than it answers. Why did the whole universe decide to run a race? Who organized it and fired the starting gun? When does it end? Do you get a prize if you finish?"

The difficult thing about explanations is that you're always limited in the amount of depth you can explore. So you have to choose between making your explanation longer, in depth, more nuanced, and more complete, or making it shorter, shallower, simpler and more superficial. The short explanation I gave had a lot of "new" concepts to most kids in there, including the idea that the Universe was smaller and that galaxies were closer together in the past, and that gravitation works on these very large scales to try and recollapse the Universe.

Image credit: NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI), via http://sci.esa.int/hubble/42355-cosmic-epochs/.

Image credit: NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI), via http://sci.esa.int/hubble/42355-cosmic-epochs/.

It also didn't touch on a huge number of things, including whether you can extrapolate this back to a singularity (you can't), whether the expansion rate is still slowing down today (it isn't), whether there's a difference in the probability of something becoming bound depending on the scale/size of the object (there is), and a number of your questions as well, Zed.

But here's one for your seven-year-old: do you get a prize if you win? If gravity wins and you do get to form a galaxy, you win the ultimate prize of all: you get not just one, but billions of chances to form worlds with intelligent life on them, and a chance at you getting to have a lifetime of your very own. That's a prize that's pretty hard to beat!

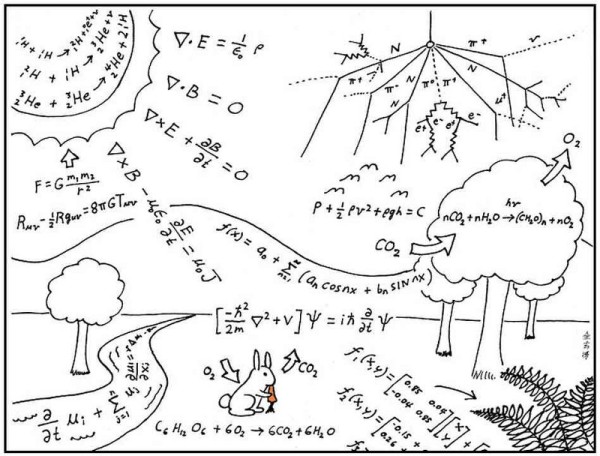

Image credit: abstruse goose, via http://abstrusegoose.com/275.

Image credit: abstruse goose, via http://abstrusegoose.com/275.

From Sean on the scientific method: "Testability yes! But to equate testability to observation requires some serious defining of the word observation. I argue that the “test” is not an observational one as this lacks a coherent definition. The test is one of mathematical self-consistency explored through the computational “observations” required by today’s science. Science has always been about collecting data and building models to understand that data. We can no longer satisfy “observation” by looking through a telescope or sampling the soil. We must use computers as our eyes and data collection as our new world to explore. This is, in my opinion, the next frontier of science."

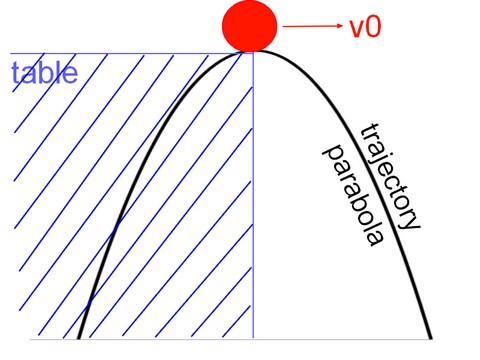

This is a common point of view held among mathematicians and mathematical physicists both, and yet it's one I strongly disagree with. Mathematical self-consistency is a necessary requirement of a physical theory, but it is not sufficient for a physical theory to be merely mathematically self-consistent. It also needs to make predictions that can be tested experimentally or observationally about reality. Take, for example, the old Newtonian idea that you're throwing a ball at some initial trajectory from a height, and the ball is going to land on the ground at an elevation below where you're throwing it from. You can start with Newton's laws of physics and all the information you need to solve the problem, and yet mathematical self-consistency will only get you so far.

Image credit: Radoslaw Jurga of Udacity, via http://forums.udacity.com/questions/9002842/some-thoughts-about-solving….

Image credit: Radoslaw Jurga of Udacity, via http://forums.udacity.com/questions/9002842/some-thoughts-about-solving….

Mathematical consistency will get you two possible solutions here, and with math alone, you have no way of knowing which one is the physically valid one. You can look at this and "obviously" choose the one with a positive distance, but that is you coming in and doing the physics that cannot be done by math alone. Mathematical consistency can get you lots of places, but not to the point where you're actually advancing science.

Image credit: Stock Photo / John Templeton Foundation, via http://www.templeton.org/templeton_report/20120919/.

Image credit: Stock Photo / John Templeton Foundation, via http://www.templeton.org/templeton_report/20120919/.

From kayvaan on quantum immortality: "So even humans 50,000 years ago somehow are still alive in some branch? Wouldn’t that require alien intervention? If so, how did the aliens achieve quantum immortality when their species was nascent? Can you bootstrap this from the beginning of time?"

I think it's important to recognize that this is a speculative idea without a lick of supporting evidence and many reasons to question its validity. As Paul himself stated when he wrote this piece:

There are major issues with the prospects for quantum immortality however. For one thing the MWI is still a minority hypothesis. Even if it is true, how do we know that our stream of conscious thought would flow only to branches in which we survive? Are all possible modes of death escapable by an alternative array of quantum transitions? Remember that quantum events must obey conservation laws, so there could be situations in which there was no way out that follows natural rules. For example, if you fall out of a spaceship hatch into frigid space, there might be no permissible quantum events (according to energy conservation) that could lead you to stay warm enough to survive.

It's a fun idea to keep in mind, but as much as I would like to believe that my beloved dog is still around and didn't die of cancer this year, she's gone. In this Universe, at least, I know she's gone. You can press up-up-down-down-left-right-left-right B A start all you like, but in this Universe, it appears that we all get one life only.

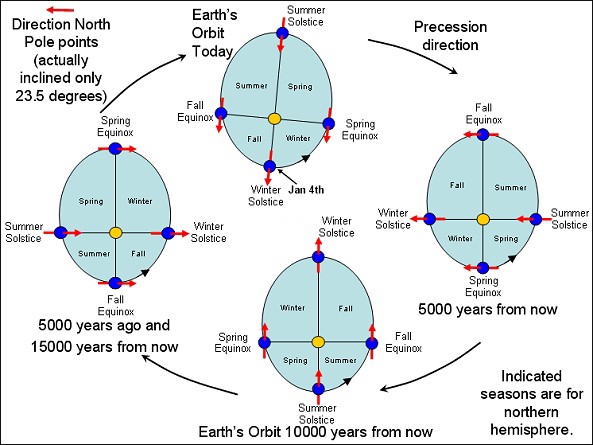

And on a more uplifting note, from Maritza Garcia on the solstice: "I found the diagram of the different positions of the Solstice fascinating. As far as I could understand your explanation this is due to the fact that the orbit precesses. Is this independent from the so called “wobbling of the Earth’s axis? Does the orbit also undergo changes in ellipticity significant enough to affect the position of the Solstice/ Equinox?"

The solstice, as you know, occurs when the Earth's axis points maximally towards (or away from) the Sun. And yet if you were to come back the very next year, when the Earth and Sun are at the exact same relative positions in space to one another, you'd find that the Earth's axis wasn't pointed maximally towards (or away from) the Sun at that moment; not exactly, anyway. It would be off by just the tiniest amount, by the equivalent of around 25 minutes over the span of a year.

There are two main contributions to this: one is the gravitational effect of the Sun-and-Moon on the Earth as it rotates about its axis, which causes the phenomenon known as axial precession, or how the Earth's tilt on its axis fails to come back to the same point in each orbit. If it were only for this effect, the Earth would have a period of precession that lasted around 26,000 years. But that number gets shortened a little bit -- down to 20,000 or 21,000 years -- because of apsidal precession, which is due to the effects of the other planets, general relativity, and other effects like the non-sphericity of the Sun. The apsidal precession is only about 12% the magnitude of the axial precession, but the effects are additive, and both impact our orbit.

Thanks for a great week of comments, and don't forget to submit your questions and suggestions here for one last chance at winning our Year In Space 2015 Calendar giveaway!