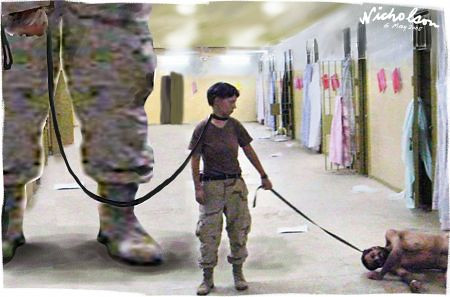

via Nicholson cartoons

Veteran, author, and blogger Kelly Williams, who was there, ponders what torture does to the torturers:

There have been lots of questions raised -- about the history and effectiveness of these techniques, the impact on those tortured, the larger foreign policy implications -- all of which are important considerations. There is, however, one aspect of the conversation that I believe has been neglected: What does this do to those committing the acts?

[snip]

Some of those who participated in the 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment (please check out that site -- it is totally fascinating!) struggled with their experiences later, one "felt sick at who he had become." Another said,

I had really thought that I was incapable of this kind of behavior. I was surprised, no I was dismayed to find out I could really be a-that I could act in a manner so absolutely unaccustomed to anything I would ever really dream of doing. And while I was doing it, I didn't feel any regret. I didn't feel any guilt. It was only after, afterwards when I began to reflect on what I had done. That this began to, this behavior began to dawn on me and I realized that this was a part of me I hadn't really noticed before.If soldiers -- or CIA personnel, or anyone -- spend months demeaning, mistreating, or even torturing other human beings, what does that do to them in the long run? How do these people treat their spouses or small children when they come home? Do they have nightmares later? Do they begin to doubt themselves? In all of the high-level discussions, the debate on whether or not these documents should have been released, let us not lose sight of this: those who were encouraged by our highest levels of government to commit torture, they too are victims.

Some difficult questions await us here. These interrogations appear to have been ordered and elaborately justified by the top levels of government carried out by an array that went from high-level CIA and military personnel down through enlisted personnel, some of whom, like WIlliams, had knowledge of standards of interrogation practice, and others who did not. Williams was apparently able to step aside; others did not. How do you parse the accountability of these various levels of agency and initiative? I'm with Andrew Sullivan and many others in feeling it's got to be done -- focusing the higher the better. But won't be easy.