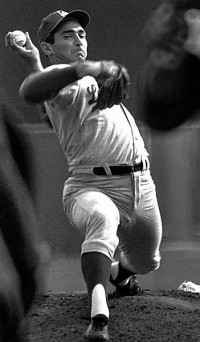

Koufax, bringing the four-seamer. God save the guy at the plate.

I always look forward to the Illusion of the Year contest, but this year brings a special treat: a new explanation of how the curveball baffles batters.

Just a few days ago, during BP, my friend Bill Perreault threw me one of those really nasty curves of his, and though I read it about halfway in, I was still ahead -- and still unprepared for the sudden slanting dive it made at that last crucial moment. The good curves do that: Even when you have that millisecond of curveball detection beforehand, they still seem to take a bend sharply and suddenly late in their path, as if some invisible hand gave them an extra tap.

This wonderful "illusion" -- really an explanation via an illusion put together by Arthur Shapiro, Zhong-Lin Lu, Emily Knight, and Robert Ennis -- explains how that happens. The curveball kills you two ways: through actual movement and an extra perceived movement that further complicates the task of getting that tiny strip of sweet spot onto the ball. (The sweet spot on a bat is about a half-inch tall and maybe 6 inches long. You have to get that small stirp, which is over 2 feet away from your accelerating hands, onto the ball .... at just the right moment, and with the bat accelerating, or you're probably out.)

I can't paste the illusion in here, but suffice to say that certain visual dynamics -- a difference between the neural dynamics of central vision and peripheral vision -- cause you to see a baseball that is rotating horizontally but falling vertically appear to fall vertically if you're looking straight at it -- but moving slantwise sideways if it's in your peripheral vision. Batters can't completely keep up with a thrown pitch as it approaches them and it effectively accelerates its path across their field of vision (from coming at them to moving past them). So at the crucial moment -- the last part of the ball's path -- you are essentially trying to track this baseball, which is usually in flight for a half-second or less, with your peripheral vision. It is in this fraction of a second -- in which the ball would be hardest to track anyway -- that the curveball actually moves the most -- and in which its real downward and sideways motion is suddenly exaggerated as it moves into your peripheral vision (cuz your eyes can't quite keep up).

That's why Bill's curveball was so untouchable. And that's why the unexpected curveball, which arrives later than you expect, sharpens its effect all the more and seems to just jump downward.

All of which reminds me of a great story Jane Leavy told in her splendid biography of Sandy Koufax. World Series in either 61 or 62, Koufax is facing the terrifying Mickey Mantle. Book on Mantle is never, ever throw him the curve, for even though you may fool him badly, he's so strong that he can still crush the ball even if his body is fooled but his hands are still not committed. So just don't throw it to him. Koufax faces Mantle three times and throws all fastballs. (The best fastballs ever known.) Third time up, crucial situation, he gets two strikes on Mantle -- and then shakes off the fastball sign, twice. Catcher catches on, puts down two fingers to call for the curve -- which was a horrid thing, a nose-to-toes diver that just killed batters, best curve in the game ... but still, he'd been told NOT to throw this thing to Mantle. But he does. Ball comes in eye-high, then dives, crosses the plate at Mantle's knees. Mantle flinched a bit but never moved. Called strike three. He stands there an extra second, then says to the catcher, "How the fuck is anybody supposed to hit that shit?" and walks back to the dugout.

Oh Sandy.

Thanks for the excellent post, and the link, which as a nice visual. (I saved it as a favorite and will show it to my kid when he comes home from baseball practice). One comment - You picture Koufax "bringing the four-seamer". A "four-seamer" is a fastball, and the article is all about the curveball. For what it's worth, it DOES look like K is getting ready to throw a four-seamer...

Since your post mentions taking BP - Do you think it is best for hitting a baseball for power and distance to have a lighter bat, so you can swing faster, or a heavier bat, because the mass is greater?

sort of like baby bear, you want a bat that's 'just right' but given a choice, go for a bat that is slightly heavier. you can always choke up. you can't make a light bat heavy.

as far as I ever understood it, you want the most momentum you can have in the bat at the point of contact. not simply the fastest batspeed. so, you may not be able to swing a certain light bat any faster than a slightly heavier bat, in which case the latter would be the better bat. at some point the weight of the bat over powers your ability to swing it and your bat speed goes down. somewhere the line of 'speed at which you can swing it' and the momentum a bat carries will cross. that's the bat you want.

On the bat size: Thinking just of momentum and force is a mistake: bat speed and quickness is huge because the quicker you can swing, the longer you can wait to swing -- which means you can watch the ball longer and make better decisions about which pitches to hit. For that reason, a lot of people think it's usually better to use the smaller of the two bat weights you're usually deciding between (31 v 32 oz, 32 v 33, etc.). The lighter bat will let you wait just a hair longer, which will improve your pitch selection, which will in turn raise your batting average -- and have you swinging at the best pitches for you rather than making contact with those you don't hit as well. Overall, you'll hit for better average and more power, because you'll be swinging at better pitches (not only because those are the ones you choose to swing at, but because -- being ahead in the count more often -- you'll GET better pitches to swing at).

The four-seamer is a fastball. I used that pic because a) I couldn't quickly find one where the grip shows he's throwing a curve and b) I love this picture anyway. It shows his motion so wonderfully: the extraordinary combination of power (the long stride, the arched back, the separation of shoulders and hips, with the hips already facing the plate but the shoulders still perpendicular as they are just beginning to be pulled forward by the hips) -- and the beautiful relaxed fluidity of his arms despite the tremendous torque and momentary tension being created by the rest of his body. Man was a god.

It must have been the '63 series - Dodgers v Yankees, Koufax was MVP.

'60 Yanks v Pirates

'61 Yanks v Reds

'62 Yanks v Giants

in '55 and '56 Koufax was on the Dodgers roster, but was rarely used and rarely effective.

however once you make contact, the bat that will provide you the greatest results is generally the heaviest one that you can swing the fastest. hence the looking for the point where the bat speed is affected by the weight of the bat, and choosing the bat just below that.

as a side note, the waiting-longer-for-the-ball bit is why when a well known curveball pitcher is on the mound every batter will try to eliminate the back line of the batter's box. by the end of the game the batters are likely to be some several inches further back then the batter's box would normally allow...

It must have been the '63 series - Dodgers v Yankees, Koufax was MVP.

'60 Yanks v Pirates

'61 Yanks v Reds

'62 Yanks v Giants

in '55 and '56 Koufax was on the Dodgers roster, but was rarely used and rarely effective.

Never got to see Koufax pitch in person, but as a young child did get to see a game with Don Drysdale pitching.

In the LA Coliseum ...

My grandfather was from Brooklyn, and was a foreman in the Brooklyn Naval Yard. In 1942 he moved to work in the Long Beach Naval Yard, loved southern california (which was lovable back in those days). When the Brooklyn Dodgers moved out, he was in heaven ... his beloved Dodgers following him to the West Coast.

That's a great photo, wrong pitch (for the article), or not.

Thanks for a great post. The co-creator of the winning illusion, Arthur Shapiro, is a friend of mine and Greta's from grad school. You should definitely check out his blog for a more detailed explanation of the illusion and more great illusions.