We are now approaching six years since COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization, yet talk of vaccines and our immune systems persists in our cultural conversations — from political arenas to the dinner table.

The vaccination conversation has extended beyond the scientific community, resulting in controversial changes to the recommended vaccination schedule for children amid other changes to public health policy and funding cuts to vaccine development.

These changes coincide with reports of rising outbreaks of infectious diseases like measles in Canada and other countries that have historically been measles-free.

Scientific evidence points to vaccines helping, rather than hindering, our immune systems. Each of us possesses a team of immune cells dedicated to protecting us against outside enemies or “pathogens” — harmful bacteria or viruses that can make us sick, like the viruses that cause COVID-19 or the common cold.

Front-line defenders

There are two kinds of players on our team of immune cells with distinct roles. The first are “front-line defenders” that stand guard and can respond immediately to intruding pathogens that enter our home turf.

These kinds of immune cells, called “innate” immune cells, are found in peripheral tissues around our bodies, including our respiratory tract, digestive tract and even on the surface of our skin. Their job is to rapidly clear pathogens by eating them in a process called “phagocytosis” (derived from an ancient Greek word meaning “to eat”) or releasing toxic compounds into their surrounding environment to target the pathogen indirectly.

Usually, innate immune cells can fight off intruding pathogens on their own. However, sometimes the enemy team is so formidable that front-line defenders are overwhelmed and call for backup.

Advanced responders

Another play that innate immune cells can make when things get tough is to pass the immune response on to the second kind of immune player, the “advanced responders.”

These immune cells, known as “adaptive” immune cells, must be activated by innate immune cells that have encountered the pathogen in order to respond.

Innate immune cells instruct adaptive immune cells on how to recognize the enemy based on unique molecular components of the bacteria or virus on the enemy team — and once adaptive immune cells acquire their target, they mount a powerful and highly specific response to the target pathogen.

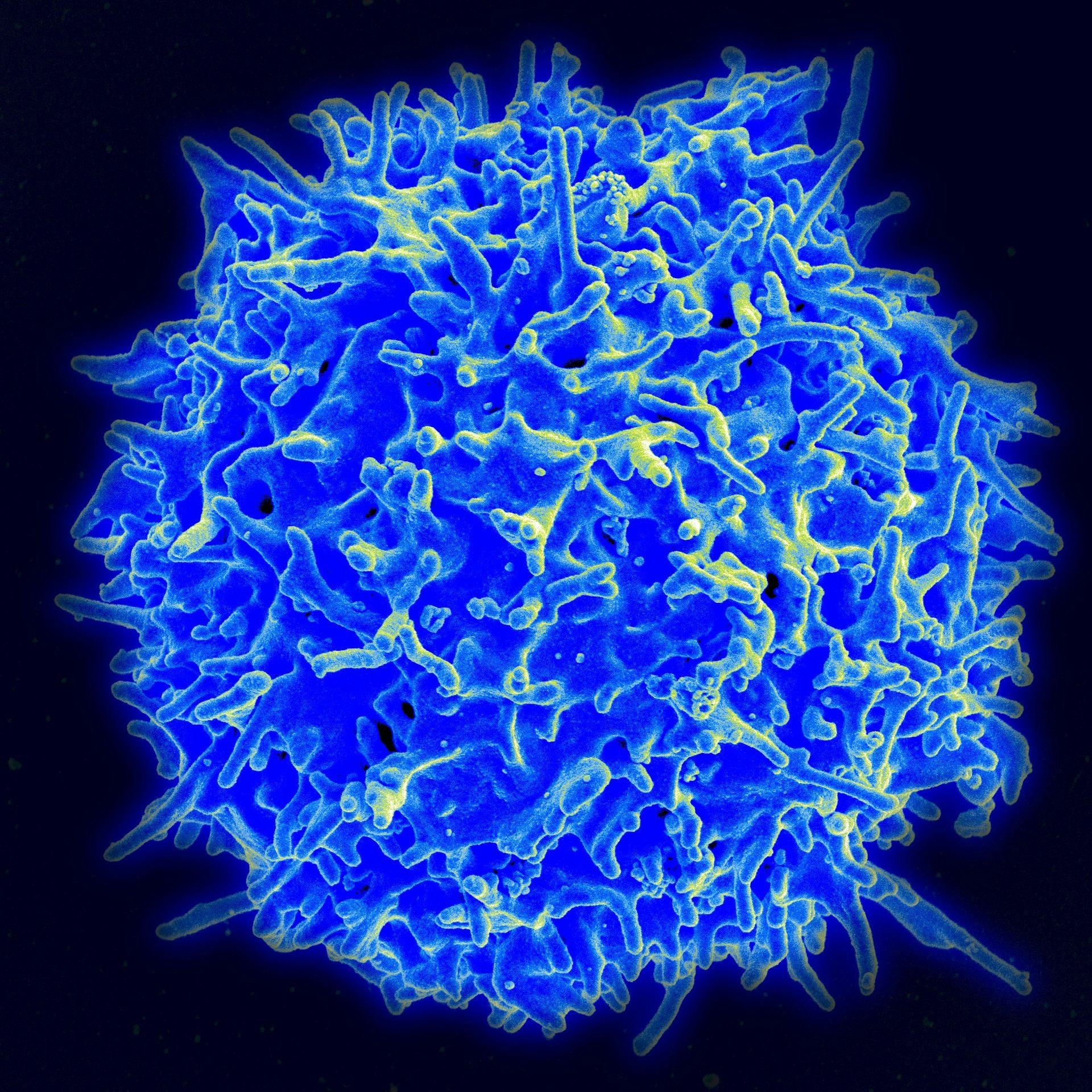

Adaptive immune cell players include B cells, which secrete antibodies — small molecular agents that bind to the target pathogens and clear them from the body — as well as T cells, which can directly kill cells infected by the pathogen or provide extra support to B cells.

Importantly, a portion of adaptive immune cell populations can retain memory of the specific virus or bacteria they learned to fight off in an infection — so if you were to encounter that same pathogen again in the future, your adaptive immune cells would be able to clear the infection much faster, without needing activation from innate immune cells.

Training the team

While our team of immune cells can develop protection against a pathogen after fighting an infection, vaccines train it in advance — without requiring us to get sick.

Vaccines contain a component of a pathogen of interest or a compromised version of the pathogen, which does not have the capacity to cause disease.

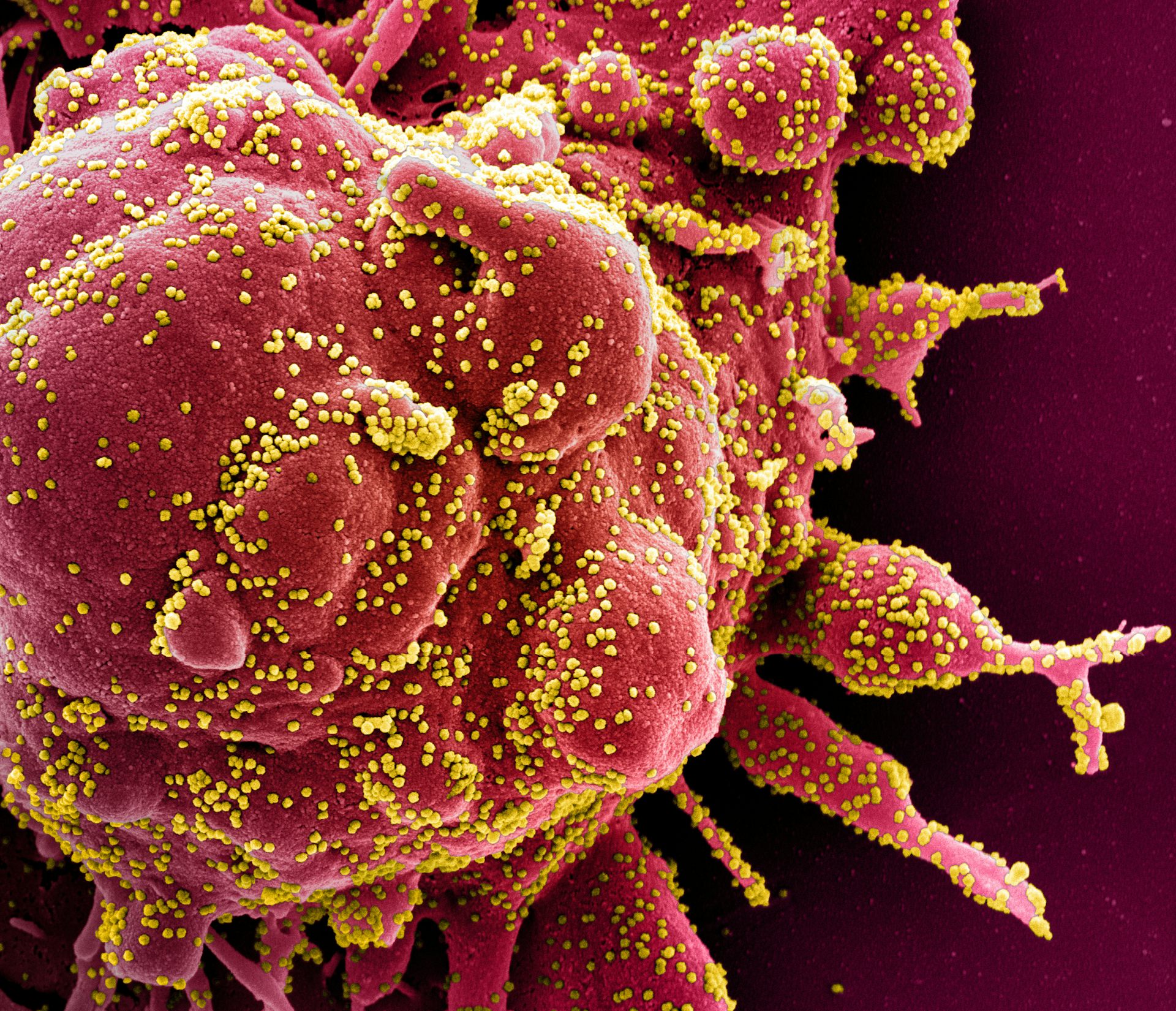

For example, the COVID-19 vaccine contains a molecule called “mRNA” that encodes a small component of the virus that causes COVID-19, but not the virus itself.

This allows our immune cells to learn how to recognize and respond to the COVID-19 virus in advance of a potential infection. Specifically, the adaptive immune cells that will retain memory of the response can provide long-term protection if we encounter the real COVID-19 virus in the future.

Put simply, vaccines train our home immune players to prepare for the big game, before they face the enemy team — which is what any good coach would encourage.

Moving forward

Vaccines, including mRNA vaccines used for COVID-19, are not a new strategy of disease prevention — they have been safely and effectively used for decades to protect us from various infectious diseases.

For example, a successful vaccination campaign against smallpox led to its eradication from the world in 1980, which is widely considered a milestone of modern medicine. Today, vaccines are tightly regulated and monitored by health-care officials, including local public health authorities such as pediatricians.

Here in Canada, new vaccine technology is currently being developed by leading researchers for COVID-19 and other diseases. These continued efforts will equip current and future generations with immune protection against old and new foes — and allow vaccines to continue to provide our team with a home advantage.

By Anthony Wong, Post-Doctoral Fellow, Immunology, University of British Columbia. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()