Welcome to part 3 of our goodbyes to the Hubble Space Telescope's WFPC2 (the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2, pronounced WHIFF-pic-too) instrument. For those of you who missed part one or part two, go ahead and check them out. And for those of you who don't remember, this was the camera that -- back in 1993/4 -- saved the Hubble Space Telescope. There was a "blurring" problem from 1990-1993, and that was the impetus for the service mission and the new, revamped, 610-pound WFPC2 instrument. The before-and-after results were immediate and stunning:

And so I bring you our third installment of saying goodbye to this instrument's 16-year run by taking a look back at some of the greatest images and discoveries ever uncovered by WFPC2.

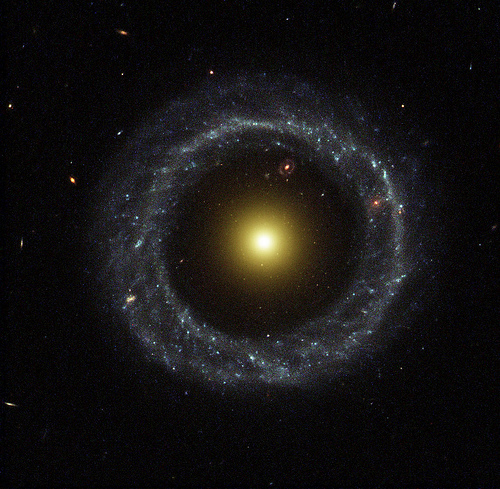

The shortest axis will collapse first, and that makes what we call "pancakes". (No, seriously, we call them pancakes, and we call the process of making them pancaking.) These pancakes spin, and that makes the nice, spiral arm structure we know and love. Some of these merge and/or interact gravitationally, and that can destroy the nice spiral structure and make elliptical galaxies. It's no coincidence that isolated galaxies are typically spirals, and that galaxies in large clusters are usually ellipticals. But what about the others? Well, in 2001, Hubble (with WFPC2) snapped this photo of Hoag's Object, a rare Ring Galaxy.

There are two theories as to what makes a ring galaxy, and they both seem reasonable.

1. Accretion: an infalling galaxy (or any amount of matter) can get torn apart by a massive galaxy, and accreted into a circular ring around it. These definitely exist, as they are the only explanation for Polar-Ring galaxies. But there may be a second type.

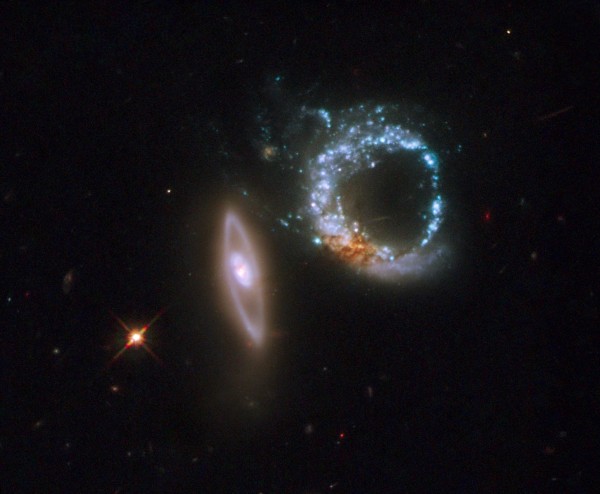

2. A ripple from a collision: a massive galaxy might pass through the center of another massive galaxy. The ripple of matter and gas that moves outwards could trigger star-formation around the ripple. This theory has been around since the 1970s, but there was never incontrovertible evidence for it. Until Hubble (with WFPC2, of course) snapped this photo (and click for the huge version):

Say hello to Arp 147, the only known pair of gravitationally interacting galaxies where both of them have rings! Based on their motion, we can tell that they're moving away from each other and they're the same distance away from us.

This means that they've just collided, and since they both have rings, this tells us that the ripple of star-formation is happening in both galaxies! It's the only time we've ever observed this for two galaxies, and we owe it all to Hubble!

|

I guess cosmology could teach tricks to magicians. I never imagined that one galaxy could pass through the center of another and still be intact after passing.

I bet the galaxies weren't as "intact" as they appear from a couple million light years away. The bluer galaxy shows some signs of damage IMO.

WFPC2 had a sticky bolt but it is finally out and WFPC3 is installed and they checked the power couplings.

WFPC2 is headed to the Smithsonian.

Mmmmm... pancakes...

Pancaking? Spaghettification?

See. This is what happens if you do physics on an empty stomach.

Awesome photos! Brilliant article! Great series! Keep on please because I had so much fun reading this. Universe is very interesting.

NewEnglandBob, It's not surprising. The distance from the Sun to Proxima Centauri is much, much greater than the diameter of either. Stars rarely collide when galaxies do.