First light is one of the most important tests of any new telescope. It allows you to look at a well-known object, see if there are any problems with your telescope, and to get a small glimpse of how good your telescope is going to be.

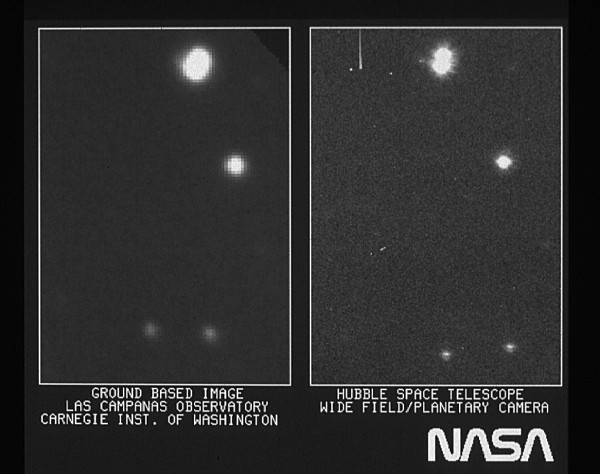

Almost 20 years ago, we launched the Hubble Space Telescope. For its first light image, astronomers zoomed in on an area of the cluster NGC 3532, an open star cluster known as the Wishing Well Cluster:

(For all images in this post, you can click on them for a hi-res version.) From this one image, we were not only able to obtain incredible resolution on the bright stars, we were able to discover some very faint stars never seen before from the ground, and we were able to first detect the problem of spherical aberration -- a mirror that was defective by just 2.2 microns at the edges -- just from this first-light image.

A little over 10 years ago, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey saw its first light, choosing to look at the well-known spiral galaxy NGC 6070 for its first light image:

Sure, the big galaxy is impressive, and we can tell that everything's working well, but the real beauty of this image is all the other things we can see in it. Stars, galaxies, asteroids, and so much more -- around 1,000 objects total -- just from this one image. This image is only about a fifth of a degree on each side, but that's not why it's spectacular. The power of SDSS is that is can take an image like this every 50 seconds, allowing it to map a vast chunk of the sky more deeply and accurately than ever before. At last count, SDSS had discovered over 500,000 new galaxies and over 75,000 new quasars. And this first light image let us know what was coming.

So, as part of the European Space Agency's amazing space program, they've just launched the new Herschel Space Telescope:

Guess what I have for you here? Herschel's first light image! They went with a classic: the Whirlpool Galaxy, M51. And I'm not going to lie to you. At first glance, it isn't very impressive.

Looks like it's blurry, low-detail, and certainly not as spectacular as many of the other images we've seen. Sure, it's infrared light instead of visible light, but so what? After all, not only is the visible light image much more spectacular and detailed:

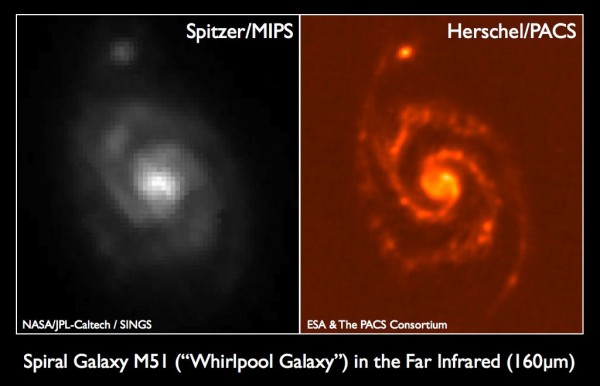

But we already have a great infrared picture of this galaxy, courtesy of the Spitzer Space Telescope:

So why should you care about this seemingly inferior infrared picture from Herschel? Because it isn't infrared like you're used to. This is far infrared, unlike the near-infrared of Spitzer. This is very important, because stars are practically invisible in the far infrared! What Herschel sees is not the stars themselves, but the neutral dust and gas around them, heated up to such hot temperatures that it shines in the far infrared. No other telescope can see these wavelength that Herschel can see to such accuracies.

Want to see what the one band that Spitzer can see the same as Herschel looks like -- side by side -- for comparison?

No contest. At 160 microns, Herschel destroys Spitzer. And at 100 and 70 microns, Spitzer is completely blind, but Herschel still sees. That's what this first light image is: M51 shown as a composite of 160, 100, and 70 microns.

And that's the potential of Herschel, to learn about the parts of the Universe our eyes would never see, but that this new telescope can uncover -- in great detail -- for the first time. So that's what you're looking at with Herschel's first light: a warm galaxy without its stars. Isn't that impressive?

Yes.

yep. impressive! Have we got any first light images from the new Hubble hardware? Or does that term even apply to the Hubble upgrade ?

What a fantastic way of illustrating what this amazing telescope is doing. Thanks for putting this together. I really enjoyed it.

What a fantastic way of illustrating what this amazing telescope is doing. Thanks for putting this together. I really enjoyed it.

http://www.ladyshoesstore.com/

What a fantastic way of illustrating what this amazing telescope is doing. Thanks for putting this together. I really enjoyed it.

http://www.ladyshoesstore.com/

What a fantastic way of illustrating what this amazing telescope is doing. Thanks for putting this together. I really enjoyed it.

http://www.ladyshoesstore.com/

What a fantastic way of illustrating what this amazing telescope is doing. Thanks for putting this together. I really enjoyed it.

http://www.ladyshoesstore.com/

What a fantastic way of illustrating what this amazing telescope is doing. Thanks for putting this together. I really enjoyed it.

http://www.ladyshoesstore.com/

What a fantastic way of illustrating what this amazing telescope is doing. Thanks for putting this together. I really enjoyed it.

http://www.ladyshoesstore.com/