I'm a great believer in luck and I find the harder I work, the more I have of it. -Thomas Jefferson

It's the end of the semester at my college as well as at many schools across the world, and I've spent the last week or so grading final exams. And while I was doing it, I noticed something astonishing. But let me start at the beginning.

Introductory physics -- without calculus -- is one of the most notoriously challenging and rigorous classes that students pursuing a career in health, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, veterinarians, and physical therapists, face in their college career. It also has a reputation for wiping students out, and (among faculty) for giving even the best professors terrible evaluations.

The reputation of introductory physics at my college is no different. So when they asked me to teach introductory physics this past year, I knew what I was getting myself into. And the first question I asked my department chair? "How does homework work for this course?"

Why should this be so important? There are three main ways I know of to do it while still requiring each student to do their own individual homework (which I support). Each has its own advantages and disadvantages. What are they?

- The classical way: students work and turn in the homework, the professor grades and returns it. The advantage? Students get their homework evaluated with the greatest care and accuracy, and get the best feedback they can: direct from the professor. They will find out what they did wrong and where they made their mistakes. The cons? It takes a long time for one professor with many other time commitments to do this. This is not just a con for the professor, it's a disadvantage for the student, who has to wait for the professor to grade every homework in the class -- by which time they're usually mired in the next assignment -- before they learn what they did wrong.

- The expedient way: students still work and turn in the homework, but instead of grading it, the professor makes up an answer key and hires a grader. The advantage to this is that students still get their homework evaluated and checked by a person, and they'll get it back more quickly (within a day or two for a good grader). The feedback they get will still often be useful and helpful, but is usually lower in quality than you'd get from the professor directly. The same downside still exists, however. By time a student gets their graded assignment back and learns what they did wrong, they're on to the next unit in class. But there is an option for faster feedback...

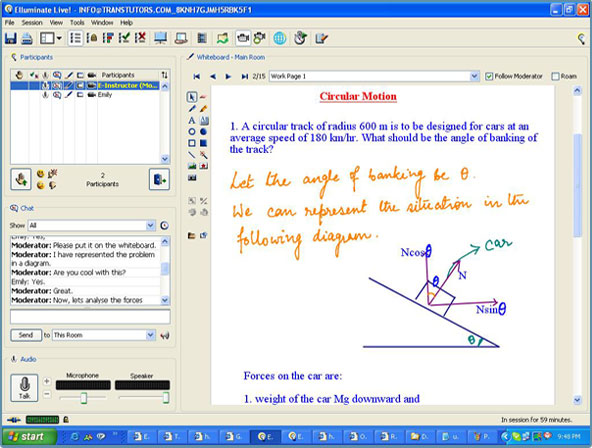

- The instant-feedback way: students turn in the homework online. As unbelievable as it may seem, this is relatively new to the scene (within the last decade or so), but it's catching on in popularity for one major reason: instant feedback. As students work through the problems, they submit their answers as they go, and are immediately told by the program whether they got it right or not. In other words, they get to learn whether they're doing it right or not as they're doing it. The cons are that -- while the expediency of the feedback they get is unparalleled -- the quality of the feedback that they get is much lower than the other two cases.

And that's really it: the three major options. My department was going with the second one, but I wasn't sure that was the best route. What did I decide to do?

I went with the online assignments, with the caveat that I would hold office hours and run a help session every week the day before homework was due for people who needed more guidance than the online system could offer. I think the homework system was set up to run very well, despite the bugs inherent in any online homework.

But it also allowed me to do something very interesting: set up online grading to my specifications. I chose to allow students an unlimited number of tries on each problem, and to give them no penalties for incorrect answers. So long as they were willing to work through their difficulties until they got the right answer, I reasoned, they should receive full credit for their homework. Who cares if you get it right the first time? I care that you get it right in the end.

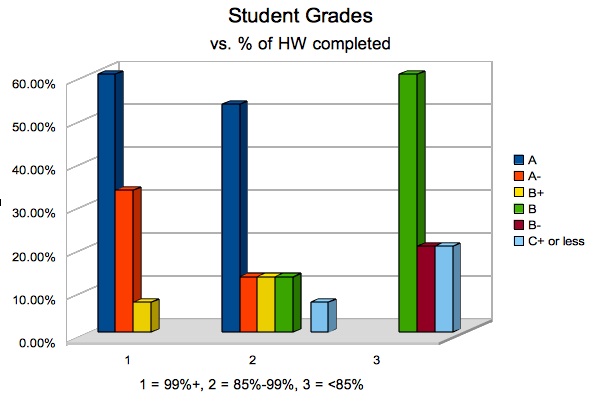

My idea behind it was that students who were diligent -- regardless of their initial aptitude -- would learn the skills they needed to in order to do well. And I thought that, if this idea were any good, their grades would bear this out. And I was quite pleasantly surprised; over a third of my students worked hard enough to get 99% or more of the points available on the homework throughout the semester. There were also many who did most (but not all) of the homework, usually giving up on a few problems that gave them the most difficulty. And finally, there were the people who -- I would say -- didn't take the homework very seriously. These were the students who did the homework when they felt like it, but didn't even attempt some of the problems, and maybe had weeks where they didn't do one of the assignments at all. Any student with a homework score of 85% or lower fell into this last category.

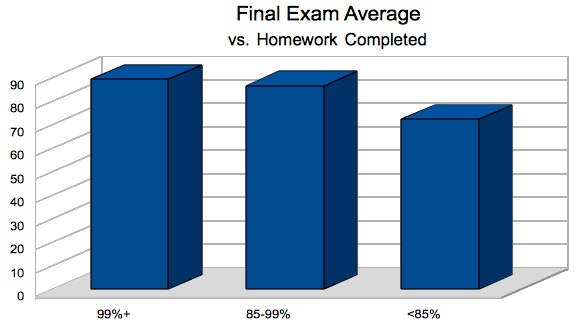

But would it matter? Would the more diligent students perform better than the others? Would the kids who didn't do all of their homework prove to me that they didn't need to do all of that homework? Well, it's the end of the semester, so we can look at the data. If I divide my students up by homework scores, how did they fare overall in the class?

(Each category of student has been normalized to 100%. And yes, some of you will lament the grade inflation. It's okay, I can take it.)

Amazing! Of the kids who worked through practically all of the homework, there was one B+, and everyone else got A's or A-'s. While if you look at the kids who often gave up on the homework, not a single one scored better than a B.

And before you think to yourself, "well, Ethan probably just counted the homework heavily in their final grade," I'd like to show you something else. Here -- again, organized by the amount of homework successfully done -- are the averages of the three groups on the final exam.

I even made a deal with everyone in the class: if you score better on the final exam than your cumulative grade to this point, your grade on the final will be your grade in the class. In other words, if you can achieve the goals of the course by the end of class, that trumps everything else; a student who did no homework but got an A on the final would get an A in the course.

And what did I find? A bunch of people got A's on the final and hence A's in the course, but of the students who did the least amount of homework? The highest grade on the final was a B. The best indicator of how well a student did was how diligently they approached the homework. It didn't matter whether it took them one hour a week or fifteen hours a week; what mattered was whether they worked until they got it. This was something I should've expected from reading Malcolm Gladwell's Outliers, but I had never expected my class' results to show this stark of a difference.

So I got to see -- as a teacher -- just how plainly hard work pays off. If you do your work until you get it right, you succeed, and if you don't, you don't. I'm sure many of you have far better stories than I just told about how important diligence and a solid work ethic is, and I'm sure that many of my students next year won't believe me even after I show them this data. But whether they believe it or not doesn't make it any less true, and I'll show you next year's results when I have them! But enough from me; what are your thoughts?

(And to those of you wondering if this post is two days late because it took me that long to figure out how to generate charts like this in Excel, you're way off. It shamefully took me two days to give up on Excel and do it in OpenOffice.)

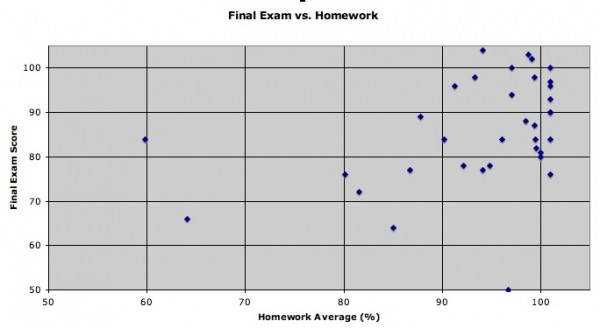

Update: This is the scatter plot of homework score vs. final exam score that James @3 asked for. (See below.)

Well, as a student myself, I feel doing homework is unnecessary unless I'm to learn something. No point to do something that I've already know; just think about it in the head is sufficient for me.

Just learn in lecturers, score in finals, and get A that's it. Or, give marks for homework and assignments. Then I'm sure to do it. Haha.

One of my lecturer provides an excel file for us to key in the answer and he programs a program to evaluate us. Haha.

You get an A++ for setting this up, executing it and following through with this report :)

Having taught this sequence at my school for three years now, and having used a combination of all three homework grading schemes throughout that time (eventually settling on #2), I can appreciate this post. Some questions:

1. What online homework program are you using? Is it text-book independent? Do all of the students have the same problems? (or is it structured to allow them to work together)

2. What was the structure/difficulty of exam/quiz questions compared to homework questions? Yes, students may be able to get the right answer eventually, but this takes time, time they don't have on an exam (which is a complaint I get).

Nice graphs, but a scatter plot of HW vs. exam grades would be interesting to see too.

This observation of yours actually correlates well with my own observations as a student (and, during my final years at university, a tutor to other students). I found early on that I would rather go to a peer instead of a professor when I had a question, because despite the gaps in their knowledge (the "lower value" of the answer), the ability to get instant feedback and interactively discuss the problem was much more important to me. Professors might take hours or even days to answer an email or phone inquiry, and their office hours were often impossible to get to, while a peer was usually readily available in the student lounge. While it might take us several tries and some research to find the correct answer to a problem, we were much more likely to stick with the issue and dig out the root of the matter if we were actively working at it, not waiting around for answers.

Of course, I was never a great fan of homework, so in your class I would possibly have been one of those who completed less than 85% of it. But then again, a system such as yours does seem to carry much more value than the standard "take it home, fill it out, get a mark back in two weeks or so" method, and I might have been swayed to turn my work in on time.

My physics classes were set up somewhat similarly with the online homework.

Except... I think this might have been what the data looked like from the first year. By the time I took the course, they'd shared the data with students. EVERYONE did ALL the homework (upwards of 95% at least). People still got Cs and Ds in the course.

Just out of curiosity, is there any record of how hard the students who did all the problems on all the homework had to work? How many tries or how much time was spent on the problems by the various groups of students? Was there some indicator that showed that the students who did all the work started in the same place as those who did not or could not complete all the problems?

In the final graph, we might suppose that the points below y=x cheated on their homework, or forgot the material before the exam*, or choked. But what of the ones above the line?

(*) This happened to me in, uniquely, Difference Equations. I did all the homework, aced the midterms, and could not recall one detail for the final. I had nightmares about it for years.

I notice that the page of notes you posted is from a calculus-based class. This means the students are already a select group compared to the introductory classes which are more common here for nursing, health professionals, and architecture students who have to take lower trig based classes or the lower level conceptual classes. The populations are quite different and the students in these classes often spend hours on HW without seeing the patterns or problem solving strategies they are supposed to teach. Do you have any statistics for those groups? I suspect the main conclusion will be the same - persistence pays off - but the way we teach physics seems to matter more to that group to keep them motivated since they often give up or wait for a less rigorous teacher to be around when they take the class.

you are a great professor. I am glad that you care about students learning the subject matter. Some professors believe that the harder the class the better teachers they are. But as a student, I appreciate learning. If it takes me 100 or 200 exercise homework problems to master it-- well i will do that. Thanks for the tip!!

This is a really great idea. I think it would be neat to expand this possibly expand this to a broader audience. Obviously I'm not speaking about you in particular but as I went through my degree which I finished a few weeks ago(engineering physics) that was a major problem that I noticed.

Often times I would try to learn the material and would simply get stuck on small aspects of problems. It would be great if a wiki-type collaboration between physics professors (or at least checked by physics professors), for a variety of courses, could create an online problem database. Step by step instructions could be available with clear references to either wikipedia or common text books to provide the required background on the theory aspect. People could add references collaboratively with explanations of why they thought that explained them best.

Just floating ideas around. Thanks for making me think Prof. Siegel!

I've tried to teach my children that neatness counts in math and physics. Being neat, and allowing plenty of room to see the process, allows the teacher to see where you may have made a mistake. It also encourages what I consider to be the correct mental approach to problem-solving: uncluttered, logical process thinking.

So far, so good. Both of my children are in advanced math and have 4.0 averages.

My own feeling is that North American Universities place far too much emphasis on evaluation. In the old days (I'm old) you were handed a problem sheet for homework, with numeric answers given. If you didn't know how to get there you asked the prof, a brighter fellow student or the teaching assistant. the homework did not count towards your final mark. Of course, the system only worked if you were keen on learning, which presumably was why you went to university. Old textbooks contained problems as well as answers. I remember reading a chapter of Timoshenko's Strength of Materials, thought I understood it, tried problem 1 and then realised that I hadn't understood it. Learning something takes some effort. I do think that the on-line approach is very good.

From my experience as a student, I found that if I had a good instructor that provided constant (and quality) feedback, I learned more from the course. As you said though, it's a two-way street, you need students to put in the effort BUT you also need teachers to put effort in providing direction and feedback.

As a student, you can put in a lot of hours doing homework but when you seldom get direction on how to improve then you're just repeating your past mistakes.

This may be off-topic but your method reminded me a bit of my art school days. We would have a model and our prof would show a demonstration of how to draw that model. Then we'd have a go at it. He would go around and individually critique and suggest some ways to improve our work. He would do this for the entire three hour class and eventually you do start to see how to do it right. After thirteen weeks of doing this, those who put in the effort improved by a wide margin.

It is about the practice but you do have to know the right way of practicing (I've heard this be called "deliberate practice").

For all I know things may have changed in the last coupla years, but the idea of having homework count towards a final grade is unheard of here in Denmark. That's something we stop doing after highschool. Once you're at uni you're free to pass your exams any way you want.

Homework for a course like this would be handled by teaching assistants drawn from the pool of grad students (840 mandatory weighted teaching hours) or hired undergrads. It would be corrected and discussed in tutorials of 20-30 people, but no grade would be given or recorded.

Question

How did scores get to be above 100%? Extra credit?

Comment

Please resist the temptation to create the graphs in pseudo-3D. They may look cool, but they make it difficult to interpret - especially #2.

Overall, I think it is a great study and gives one a lot to think about.

As a physics teacher of 17 years my direct experience duplicates Ethan's. I have told students for many years that a fundamental for success in my course is doing the homework and doing it YOURSELF, not just copying it. I always encourage students to collaborate outside of class but never to just copy something without clear understanding and the ability to then successfully do a different problem on your own.

Students who were conscientious and did all of their work never scored less than a B.

I take a bit of umbrage about the international method of grading by exam only. I find that those students do not know how to do much but take exams. Place them in the lab and they do not perform as well (I have 13 years of university physics research experience). The US method of grading varied work has resulted in more innovation per-capita than any country in the world. Simply look at inventions and Nobel prizes. And I am not a dogmatic jingoist, I am an open-minded liberal old hippie. :)

Last semester I completed a math education course, and read

Kilpatrick et. al. (2001), which discussed the lack of research in the value of homework, and I must admit, this suprised me. Whereas homework is widely viewed as a useful supplement to classroom time, little evaluation of the nature of that homework has been done. The only correlation noted is the linkage between quantity of homework and class score. We would all agree procedural facility is desirable because it enables automaticity and frees cognitive resources for other tasks. Procedural facility is achieved by drills and practice. However, problem solving can also become a mental habit through practice. We are lacking studies that review the development of higher level cognitive skills via homework. Ethan's statistics are not just on quantity but on scores, and that's a starting point. If we could segment the homework further into the thought level required, that would be more informative.

I have similar experience with online homework systems as a high school physics teacher. Ethan challenges me to develop similar statistics for my classes. My sense is the pattern will look the same. We can draw the conclusion that those who are diligent score better in the course, and that is the mark of quality in every facet of life.

I also teach AP Chemistry, and had one very bright student who submitted almost no work through the course of the year, yet tended to score well on tests. Throughout the course of the year, however, his grades worsened, and by the time he actually took the exam, he declared, "That exam was the hardest exam of my life!" All of the other students, who had worked so diligently all year, secretly (or not so secretly) rejoiced, because they innately knew "nothing in, A's out" is NOT sustainable or even possible.

I think the instant feedback of online homework systems is invaluable, but some systems are better than others because of the tutorial aspect they provide. I have used masteringphysics.com and webassign.com, and much prefer masteringphysics.com because it provides tutorial help.

In the two years I've used online systems, I migrated to the same format Ethan uses: unlimited tries and no deduction for wrong answers. We are trying to provide an environment for mastery, and some students will take more attempts than others to get there.

Thank you for sharing your results with us, Ethan!

Ref: Kilpatrick, J., Swafford, J., & Findell (2001). Teaching for Mathematical proficiency. Adding it Up: Helping Children Learn Mathematics. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Ethan,

For comparison, did you see how long it took students or how many tries? I know you didn't penalize students for trying over and over but I'm curious if those who knew it right away did better in the long run or conversely if the hard work saw improvement in the people who took several attempts.

Good analysis. As an experienced teacher, I would point out that correlation does not imply causation.

Yes, the students that did all of their homework also scored well on the tests. That does not necessarily mean that the homework drove the grades. It is certainly possible that the students who do all of their homework are also the ones who have developed good study habits and are the most well-prepared for a rigorous course. It could be that the ones who do not do their homework are also lazy about studying and taking notes.

This is not to refute your conclusion - just to say that there's more to the picture than you've portrayed.

I also do online homework, and its a great tool for those who are inclined to make use of it. There are shortcuts there also (online answers, etc) that subvert its intentions.

My own feeling is that North American Universities place far too much emphasis on evaluation. In the old days (I'm old) you were handed a problem sheet for homework, with numeric answers given. If you didn't know how to get there you asked the prof, a brighter fellow student or the teaching assistant. the homework did not count towards your final mark. Of course, the system only worked if you were keen on learning, which presumably was why you went to university. Old textbooks contained problems as well as answers. I remember reading a chapter of Timoshenko's Strength of Materials, thought I understood it, tried problem 1 and then realised that I hadn't understood it. Learning something takes some effort. I do think that the on-line approach is very good.

So long as they were willing to work through their difficulties until they got the right answer, I reasoned, they should receive full credit for their homework. Who cares if you get it right the first time?

In the real world, when you turn in your project to your boss; he/she cares if it's right the first time.

Your students will get that cold shower of reality along w/a pink slip if they assume that incorrect mathematics are acceptable in the private sector, where monetary decisions will be made based upon their work.

"It didn't matter whether it took them one hour a week or fifteen hours a week; what mattered was whether they worked until they got it."

I don't see how you can draw this conclusion, since the amount of time spent on homework is not measured. For example, if each of your students spends an equal amount of time on homework, it would be unsurprising that the amount of homework they finish correctly correlates with their exam scores.

Does your homework program keep track of the number of incorrect homework answered before getting the problem correct? You maybe could use that as a measure of the amount of time a student spends on the homework. Giving repeated tries with no penalty for wrong answers seems like a very interesting idea for improving the effectiveness of homework, though, just thinking intuitively. It's something you could not possibly do with traditional grading methods, it would just take too much time.

I got envious looking at those test scores. I remember a physics test from when I was an undergrad where half the class got NONE of the answers correct. That is Caltech for you.

Hello,

please, i want physice formula, i mean the basic plssssss thank you.

My own feeling is that North American Universities place far too much emphasis on evaluation. In the old days (I'm old) you were handed a problem sheet for homework, with numeric answers given. If you didn't know how to get there you asked the prof, a brighter fellow student or the teaching assistant. the homework did not count towards your final mark. Of course, the system only worked if you were keen on learning, which presumably was why you went to university. Old textbooks contained problems as well as answers. I remember reading a chapter of Timoshenko's Strength of Materials, thought I understood it, tried problem 1 and then realised that I hadn't understood it. Learning something takes some effort. I do think that the on-line approach is very good.

My own feeling is that North American Universities place far too much emphasis on evaluation. In the old days (I'm old) you were handed a problem sheet for homework, with numeric answers given. If you didn't know how to get there you asked the prof, a brighter fellow student or the teaching assistant. the homework did not count towards your final mark. Of course, the system only worked if you were keen on learning, which presumably was why you went to university. Old textbooks contained problems as well as answers. I remember reading a chapter of Timoshenko's Strength of Materials, thought I understood it, tried problem 1 and then realised that I hadn't understood it. Learning something takes some effort. I do think that the on-line approach is very good.

My own feeling is that North American Universities place far too much emphasis on evaluation. In the old days (I'm old) you were handed a problem sheet for homework, with numeric answers given. If you didn't know how to get there you asked the prof, a brighter fellow student or the teaching assistant. the homework did not count towards your final mark. Of course, the system only worked if you were keen on learning, which presumably was why you went to university. Old textbooks contained problems as well as answers. I remember reading a chapter of Timoshenko's Strength of Materials, thought I understood it, tried problem 1 and then realised that I hadn't understood it. Learning something takes some effort. I do think that the on-line approach is very good.

My own feeling is that North American Universities place far too much emphasis on evaluation. In the old days (I'm old) you were handed a problem sheet for homework, with numeric answers given. If you didn't know how to get there you asked the prof, a brighter fellow student or the teaching assistant. the homework did not count towards your final mark. Of course, the system only worked if you were keen on learning, which presumably was why you went to university. Old textbooks contained problems as well as answers. I remember reading a chapter of Timoshenko's Strength of Materials, thought I understood it, tried problem 1 and then realised that I hadn't understood it. Learning something takes some effort. I do think that the on-line approach is very good.