"Be careful. People like to be told what they already know. Remember that. They get uncomfortable when you tell them new things. New things...well, new things aren't what they expect. They like to know that, say, a dog will bite a man. That is what dogs do. They don't want to know that man bites a dog, because the world is not supposed to happen like that. In short, what people think they want is news, but what they really crave is olds...Not news but olds, telling people that what they think they already know is true." -Terry Pratchett

We all like to think that our opinions are the result of years of hard-earned accumulation of knowledge. That we've gone and aggregated all of the relevant facts on a particular issue, put them together in the most sensible way, and that's how we've arrived at our picture of the world.

But, of course, that isn't the way we work at all.

Known as confirmation bias, it's the very human tendency to, once we've formed an opinion, place our faith in the new evidence that appears to support that position, but to look for holes in the evidence that undermines or disagrees with that opinion.

In other words, changing our minds -- especially once we've made our minds up -- is extraordinarily difficult. The way we often deal with this, in the case of a divisive issue, is to think that the other side on an issue is (any combination of) misinformed, ignorant, foolish, or conspiring against the truth. And we often miss no opportunity to present them (and their position) as inferior to our own.

When was the last time you saw someone who held a passionate position on one side or another of a divisive issue actually change their mind and switch to the other side in the face of overwhelming evidence? It doesn't happen very frequently, does it?

You may not see it very frequently in your own life, in politics, or most places that you look, but it happens all the time in science. Not for everyone, of course, but science is one of the only places where you'll see a vast majority of scientific experts in their field change their mind on an issue based on the evidence that comes in.

When a uniform-temperature, all-sky microwave radiation background was discovered in the 1960s by Penzias and Wilson (above), it provided overwhelming scientific evidence supporting the Big Bang picture of the Universe, and disfavoring alternative explanations such as the Steady State theory. A few notable exceptions held out, but modern cosmology simply does not make sense without the Big Bang, and this was the observation that sealed it.

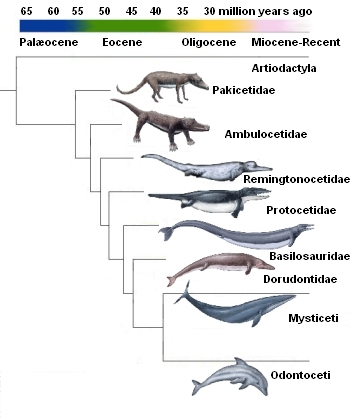

Same deal with evolution. Without it, modern biology -- including genetics, DNA, and modern medicine -- makes no sense. Evolution was an amazing idea that came in multiple variants for a time, but when the archaeological evidence of transitional fossils started pouring in, it became clear that all living things on the planet were descended from previous generations of living things dating back at least hundreds of millions of years. (We know that's longer, now.) Even transitional forms for organisms like whales and dolphins exist, and when this type of evidence started rolling in, even the most skeptical of competent scientists started changing their minds.

And in a very notable recent example, climate science skeptics such as Richard Muller, above, are overwhelmingly concluding that there is a link between the observed rising temperatures of the Earth and the effects of human activity, once again in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence. As always, there are holdouts, but that does not change the scientific facts or conclusions.

My favorite example, though, of a scientist who held strong convictions on an issue, but changed their mind, dates back more than 400 years!

Towards the end of the 16th Century, after the death of Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, pictured above, was -- perhaps along with Galileo -- the foremost astronomer in all of Europe. Much like Galileo, Kepler was intimately familiar with the work of Copernicus, and recognized how beautiful the possibility of a heliocentric Universe was.

After all, it could explain the retrograde motion of the planets -- how some planets appeared to reverse direction with respect to the fixed stars -- in their motion from night-to-night!

Instead of a stationary Earth, where the planets orbit the Earth in a superposition of circular orbits, occasionally reversing course and appearing to move backwards, the heliocentric model had the outer planets (Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, etc.) move backwards because the Earth, in its faster orbit around the Sun, overtook the outer planets in their position! (Mars, for those of you astutely watching it, is finishing up its retrograde motion as I write this!)

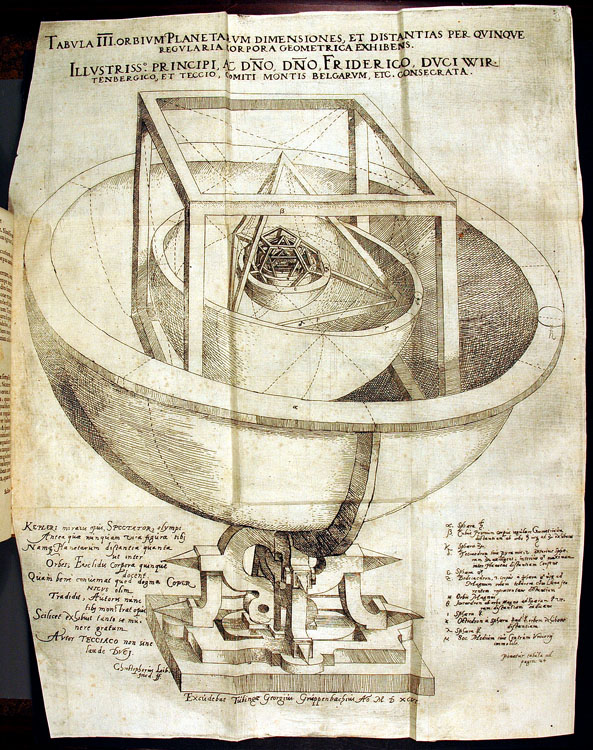

This is nearly a hundred years before Newton's gravity, so there was the great question of how these orbits came to be. And Kepler's idea was nothing short of genius. Sheer, unbridled, and beautiful genius.

Envisioning the six planets as being supported by the five Platonic solids with spheres inscribed/circumscribed upon them, the orbits would be defined by the circumferences of these spheres. It was a beautiful idea, with very explicit predictions for the ratios of the scales of the planetary orbits. Because there are only five Platonic solids and were only (at the time) six planets, this scheme was beautiful, compelling, and created an incredible buzz amongst scholars.

But unlike Galileo, Kepler had access to the finest data in the world: the observations of his predecessor, Tycho Brahe. And the data simply did not agree with Kepler's theory. The orbits were all wrong.

Not by that much, mind you, but by enough that it clearly didn't fit. At the time, there was tremendous prejudice in favor of the circle being the only acceptable shape for an orbit, but -- ever the scientist -- Kepler followed the data to its logical conclusion. He even rejected his beautiful Mysterium Cosmographicum, creating, instead, the model we use today.

They're not circles, or a superposition of a number of circles at all; the orbits are ellipses! Planets move around the Sun with the Sun at one focus of an ellipse; the first of Kepler's three laws of planetary motion!

And so Kepler was able to throw away the most beautiful idea he ever had, and in place of it, discover the way the Universe actually worked. And that's my favorite example of defeating your own confirmation bias; from more than 400 years ago! That's the reward of being honest with yourself, one of the most difficult things, apparently, for us, as humans, to do.

So let me ask you; what's your favorite example, from your own life, of when you changed your mind on an issue, based on the new evidence that you learned and couldn't ignore?

When I was about 18 I knew everything. Then I went to college and met the rest of the world. I was convinced that population should be limited by law since we were overpopulating the planet and there were so many people who lived without basic necessities. I was sure this was the enlightened view and that all thoughtful persons would agree.

Then I started hanging around with a bunch of people from Africa (grad students with families). When I blurted my first-world opinions I was gently put in my place by my exposure to third-world reality (low survival rates for infants, need for labor, etc).

I decided I would allow the rest of the world to make up their minds about what was best for them.

By the way, I love Kepler's history. I used him as much as possible in my physics classes for the same reasons you point out (frickin' Mars....not circular.....maybe ellipse.....wow!) I also used his laws to point out that you can have a formula that describes what is happening without having a theory to go with it.

The kids appreciated that Newtons law of attraction has Kepler's Second law built in!

I got annoyed when that law was given as T^2/R^3 = k.

If you use it as R^3/T^2 = k you can use the constant for a planet's mass. Made lots of weird problems easy.

Essentially, I was a born again young earth christian who knew how everything came into existence, how it all worked, and where it all goes. Then those liberal college professors selling socialism and facts! Of course, what happened, and it took many years, was I learned to think critically, and I majored in Anthropology, took physics and astronomy classes, and well, there you go. It was ten years at least to go from a non questioning sheep to pretty much what I accept today. A testament(ha!) to the power of confirmation bias and religious indoctrination.

And, oh, anybody upset by the Dilbert guys response to the Limbaugh/ Fluke issue? I will be avoiding Dilbert for now.

http://dilbert.com/blog/entry/the_limbaugh_fluke/

I used to think pot smokers were just one step from meth addicts and any time spent around them increased my odds of getting robbed for potato chip money.

Now I know they are far more boring than that and support their desire to be legally sleepy.

I used to think Homeopathy was a load of crap, and now....uh, hang on, let me try that again.....

I used to be the standard homophobe in redneck country, until my older sister came out as gay & revealed that all her cool friends that I liked were actual, real-life fags, it changed the meaning of the word for me and my whole attitude.

My story is the same as Waydude's above, except that my deconversion from Christian Fundamentalism happened a year before I got to college. I decided to rationally analyze my beliefs and see if they were consistent with observation. Lo and behold, they weren't. Now I'm on a real adventure, and loving every step of the way :)

Similar to others above, I was a young earth creationist. Went to Bible College, learned Koine Greek, some Hebrew, various philosophies, history, other religions, and picked up two bachelor degrees in theology plus a diploma (fully accredited, by the way, and it was harder work than anything I've taken since except for my fourth year of my science undergrad--even my grad work wasn't as hard as the 4th year).

I used to argue with evolutionists and I was convinced I was right not because of their science, but because of their really poor philosophical arguments. I'd laugh at their strawmen arguments and assumed since they were so ignorant of what religion and Christianity were about, then why should I bother listening to them on any topic (that's why many Christians dismiss what Dawkins has to say--i.e. he sets up strawmen and doesn't have much background in religious philosophy so makes laughable errors. Too bad because he's brilliant at explaining things when it comes to science).

Then I decided to start a new career and I went back to school for degrees in science (biology). Slowly I learned that many of the things I'd learned about young earth creationism were wrong. As an aside, YEC wasn't taught at the Bible College--I just "edumacated" myself with books by Gish and others. Not debatable, not interpreted differently, but factually wrong. I found misquotes, things taken out of context, papers that were supposed to support YEC actually said the opposite.

It took 10 years of schooling, reading, learning to change my mind (Dawkin's The Blind Watchmaker was my watershed moment as it answered many questions). I had a lot invested in my beliefs, I had experienced that transcendent peace through prayer in difficult times, I had experienced forgiveness that left me feeling like I was walking on air and glowing with light. I was part of a loving community and felt at home any place I went where other believers were present. It was all amazing.

But I was unable to reject just the YEC parts and leave the rest. If the YEC parts were so wrong, then perhaps all the rest was wrong as well, so I jettisoned everything. Maybe a illogical decision (baby, bathwater, etc) but no real choice. Many people have no difficulty believing in God and accepting evolution, but I'm not one of them.

It was pretty rough 10 or so years (probably 15 years before I was really settled and comfortable in my new 'skin'). I really have to follow the evidence where it leads--I have no choice. Fortunately, it is now very easy for me to change my mind when new evidence comes in. Compared to what I've already done, everything else seems so inconsequential and trivially easy to change.

I used to think prison was the natural place for criminals. It is what society says we should do with them, right?

Then I went to prison, and saw what it was, and what it did. Still, it was the place for the really bad people, and drug addicts, right? So it took me reexamining the whole idea, and going through recovery, meeting drug addicts, to finally realize, we are putting sick people in a dark closet, just so we don't have to think about them anymore.

Addicts are in need of help, not in need of watching, yet the prison industry is lobbying congress to increase prison times, and include more crimes as rating a prison sentence.

I finally had to realize that we have never been able to stop anything that we have made illegal, and many of the things that we have made illegal, have created situations that caused our society harm.

I was confused (by religion) and uninterested in about everything until I read Dawkins' "The Selfish Gene". The change was sudden and profound: first time in my life, I saw that there really is reason in nature (no need for external designers or controllers); the wonders of reality are overwhelmingly beautiful - and I'm fully part of it. No boring supernatural stuff can ever even dream of getting nowhere close to being worth giving another thought, ever. Now I'm reading everything I can about everything in nature, where/when/how it all begun, how it evolves and works and where it's going. The only way I can describe the change in me is that I'm almost physically a different person: previously, I was slightly depressed and had really low self-esteem but I'm now getting better and better the more I read and observe about (and now live WITHIN) the reality around (and inside) me. And SWAB has been one of the most educating delights in my new life.

Yesterday evening I went out, it was full moon and for the first time I realized that I was able to find Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Betelgeuze just by looking up and reasoning, based on the information I've acquired reading SWAB. Wow, I thought.. And then I just stared at the tiny dots and wondered about gravity, replaced the picture models of the Solar System with what I saw with my own eyes; I've never looked at the sky like that, "feeling" the gravity between the planets and the Sun.. And then Betelgeuze, the small blink in the sky, extending in size over Mars' orbit if centered on top of our own, closest star.. I love to read about dark matter and dark energy now, before I just couldn't care less.

It's a wonderful life when you really get to see it as it is, without any religious beliefs distorting (or blocking) the view. This is based on my own emotionally rich (and only too recent) experience.

"that's why many Christians dismiss what Dawkins has to say--i.e. he sets up strawmen and doesn't have much background in religious philosophy so makes laughable errors."

I think both Richard and myself, among many many others, would like to know what these strawmen and laughable philosophy errors are.

Did you know that Kepler published a second edition of the "Mysterium Cosmographicum" 25 years after the first? The second edition came after he had published the works in which one can find his First, Second and Third Laws. The preface to the second edition makes it clear that he regards the ideas of the "Mysterium" still to be valid.

Because Kepler left so complete a record of his thoughts as he worked through his life, we have many instances in which he manages to keep several conflicting ideas together without realizing that they conflict. This may be one of them. It is probably a bit of a stretch to say that

"He even rejected his beautiful Mysterium Cosmographicum"

"It is probably a bit of a stretch to say that

"He even rejected his beautiful Mysterium Cosmographicum""

Except it is a fact that he did.

His explanation and workings show that his other theories didn't fit.

However, nobody says that once you find "the" answer, you shouldn't bother looking to see if you had it right before all along.

See, for example, the cosmological constant. If Albert had held on to his idea he dropped because it didn't work, he'd have maybe found something. Since the risk would be spending time on something that really WASN'T going to pan out, he may have been wise to pursue something more immediately productive.

that's why many Christians dismiss what Dawkins has to say--i.e. he sets up strawmen and doesn't have much background in religious philosophy so makes laughable errors.

There are so many different varieties of Christianity that it is hard to make any but the most superficial statements that would be true of all sects that call themselves Christian. Dawkins may be making certain statements which are true of the Church of England (which, I remind you, is a state-affiliated church--separation of church and state is an American innovation) but are not necessarily true of Southern Baptists. Likewise, his philosophical arguments might apply to the Church of England but not to various evangelical Protestant sects. Mind you, I don't know if this is the case (I am no expert, nor a member of the Church of England), but it is certainly plausible for different people to have wildly divergent ideas of what a Christian should be.

Case in point: Fred "Slacktivist" Clark, whose blog postings I occasionally read, talks often about Christian philosophy. He comes from an evangelical Christian background himself, and is still at least nominally of that faith, but he is deeply critical of other evangelical self-proclaimed Christians who seem to focus on little rules while losing sight of the big picture. (My experience is consistent with Clark's; I find that the vehemence with which somebody proclaims himself to be Christian is correlated with the extent to which he follows certain little rules and ignores the big picture lessons attributed to Christ in the Gospels.)

Good post, but you probably want to reword this:

I had to follow the link to your other post to make sure you aren't one of those people who thinks the "link between the observed rising temperatures of the Earth and the effects of human activity" is "in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence."

Wow, you got the full Bingo card of fake sceptic memes in your comments over there. Well look at it this way, a lot of poor bastards hired on elance got an opportunity to earn their supper money.

Ironically: climate. I was so taken in by the evidence of climate change that I got rid of my car in 2007. And then I became a climate skeptic. Mainly on two points:

- Uniqueness of current climate change

- Magnitude (and sign!) of the feedback

I don't doubt that CO2 does warm the planet, but I think 0.5 degrees Celsius per doubling is much more in line with the known evidence.

What I really find awful is that humans are hurting other humans and destroying the eco-system in so many ways, that a reduction of the discussion to "It's CO2" is not only scientific false, but will seriously bite us in the arse. We have already caused the biggest extinction event â wholly without CO2. We are pushing so many people to poverty and are quite happy to declare it "their own fault". But when it is supposedly CO2, we suddenly care? If you want to save the planet, then there are many ways that are IMHO much more credible then "reducing the carbon footprint".

I used to think that "there might be something to" homeopathy. Basically, I confused it with herbal remedies and thought there was some active ingredient. Then I found out that it was sugar pills and water, and heard about the studies that found no effect beyond placebo (thank you, Ben Goldacre).

More controversially, I used to think that giving aid to developing countries was an unalloyed good. After talking to some people who worked in sub-Saharan Africa, I'm more skeptical (not to say it's always bad, but you should do your homework before contributing).

"And then I became a climate skeptic. Mainly on two points:

- Uniqueness of current climate change"

Que? When was the last time CO2 was produced in such quantities over such a short time? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Permian%E2%80%93Triassic_extinction_event would be it. Guess what happened to the dominant species.

"- Magnitude (and sign!) of the feedback"

Yup. You know your amplifier? It as a positive feedback. Doesn't seem to mean you don't get any music out of it. And given our current atmosphere has up to 20% of the warming from CO2 and over 60% from H2O, a 3x or higher feedback multiplier is absolutely reasonable.

"but I think 0.5 degrees Celsius per doubling is much more in line with the known evidence"

CO2 1850: 290ppm

CO2 2010: 395ppm

T(2010)-T(1850): 0.8C

CO2 hasn't doubled by a long chalk, yet we've got more than 0.5C warming.

What evidence did you have? Some other planet's climate?

"We are pushing so many people to poverty and are quite happy to declare it "their own fault". But when it is supposedly CO2, we suddenly care?"

In each case of the use of "We", please show that they are describing the same people.

These comments are every bit as encouraging as Kepler's honesty. Very nice to hear other's struggles to be honest with yourself.

The problem is what do we mean by honesty? How much of a rebel do we really want in ourself and others? Do we wanted to be totally open, totally revolutionary in thought and action, totally to question; could we take the social isolation, the risk to friendships and career?

Let's not pat our scientific selves upon the back too proudly. There are stories of betrayal, of dishonesty in science. And there are stories of honesty and courage in religion, arts and other fields (e.g. from Socrates to Martin Luther King to Virginia Woolf to Rauschenberg to Jobs to you and me)

Every social group has its revolutionaries, visionaries as well as its Luddites.

Sir Arthur Eddington not only declared that there could be no such thing as a black hole; he destroyed the career of the young Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar. Chandrasekhar astronomy career was ruined; thus he reinvented himself in another field. Many years later, the extraordinary scientist Chandrasaekhar returned to astronomy.

And what about astronomy, astronomer's were too intimidated (for their careers) by the great Eddington to publicly disagree with him about black holes; and the science of black holes was delayed decades until after Eddington's death.

In comparison, Einstein's disagreement about quantum mechanics destroyed no careers or even slowed the science; rather his clear headed debate gave positive challenge and enriched the developing quantum mechanics.

Or more recently, consider the recent book Merchant's of Doubt by science historians, Erik M. Conway, Naomi Oreskes. They were shocked to find the very same physicists (e.g. Frederick Seitz, former president of the United States National Academy of Sciences) at the heart of science misinformation campaigns that tobacco poses no health risks to there is no global warming. Seitz used his scientific credentials to create the illusion of scientific honesty in scientificly important public policy issues.

Science is not immune to dishonesty, to the politics of career, to greed, to unreason. In all fields, only the clear headed can face the unreasoning mob, bias, our own hypocrisies etc.

It is very hard work to be honest with ourselves. On a humorous note, in the pre internet age; we could laugh at print ads and television ads. But in the internet age; we have to be honest and ask ourselves, "what have I done to deserve this cheap, stupid, mindless advertisement?" Because we all know that privacy is an illusion and those ads are targeted at me, oh no!!

Ethan, ahha, I see that you also take inspiration from Kepler's beard. Very nice.

Re: that "Moran" sign.

There is a Northern Virginia congressman named Jim Moran. His critics sometimes refer to his supporters as "Morans" in a play on words.

So, that sign may not be anywhere near as idiotic as it looks.

I don't know if this is the origin of the sign or not. It probably doesn't matter - the point is, what appears to be ignorance on someone else's part is sometimes ignorance (of context) on our own. Whick kind of supports Ethan's big point about biases.

When I first read about Modern Monetary Theory, it sounded like complete bunk, I'd actually get angry reading it because it contradicted what I thought I knew. The more I read, the more I realized it made sense. I had to throw away a large number of assumptions I'd had about economics, but it does fit more of the data than other economic theories. It took months of study, but I understand economics better now.

As a small comfort to those with new ideas out there, but who have been designated as "cranks" or "crackpots" by the establishment, let me offer this:

Max Planck in his "Scientific Autobiography" said this, "A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it." (Quoted in Gerald M. Weinberg's "An Introduction to General Systems Thinking")

As a small comfort to those with new ideas out there, but who have been designated as "cranks" or "crackpots" by the establishment, let me offer this:

Max Planck in his "Scientific Autobiography" said this, "A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it." (Quoted in Gerald M. Weinberg's "An Introduction to General Systems Thinking")

"I used to think I didn't understand the universe, now I know I was wrong" - Sheldon Cooper ;-)

I'm a for-real child of the space age; that is, I grew up believing that I would be working in space and that there would be manned missions to the outer planets by 2001. FTL? somebody would crack that one sometime in the 21st century, and probably sooner rather than later.

Now? After suffering several knocks to the head I've come to believe that: no ftl, no easy control of gravity, no space colonies, and no manned missions to any planet any time soon. And even the mundane stuff like switching over to solar power is much, much harder than it first looked when I was fourteen or fifteen. I'd thought that would have happened some time in the 80's ;-)

I actually was able to surpass the arrogance of being indoctrinated into the religion of science and being a devout atheist and found enlightenment and happiness, and the meaning of life. Though I am not what most would say is a "christian" I understand the psychology behind Christ's method (from a Tibetan Buddhist perspective) and respect the method.

On top of that I now know not only that there is a God (as a supra-consciousness/fractal perspective, not a white bearded old man perspective), but basically why there is a God, which is perhaps more important.

As Galileo said, "it moves anyways" ... God Is anyways; and so are the 8 Dharma (laws) that define him and us: Karma, Evolution, Relativity, Conservation, Vibration, Rotation, Polarity, and Resonance.

The failing of atheism is that because one cannot see, therefore one concludes it does not exist. That is NOT the scientific method. It has sadly become part of the religion of "science" which pervades all over and has led to the ravaging of our planet and development of massive weapons and has done little to fix the basic problem in the world: how can we be peaceful and happy? REAL Science is a study, and when I realized it had become a religion and my atheistic view basically ignored all the evidence in non-linear mathematics, and statistics, as well as the obviously conscious-guided aspects of the evolutionary process (how else could a species adapt to a specific function unless it wanted to (and since a bird is minorly conscious, only a supra-consciousness of the species could do this)).. well then I decided I didn't know anything WORTH knowing. I had a lot of facts as an engineering and math major, but I couldn't help anybody with what really matters in this world: healing each other. My science would go to either modding war helicopters or making new gizmos to sell to unsuspecting consumers. That is not the Way. That is not who we are meant to be. And also it rapes the planet and defied my environmentalist paradigm.

The ONLY explanation for this need that came to me, in my mind and soul... is a loving supra-consciousness; bodhi is the need, whence comes bodhi? Call it God, Krishna, the Multiverse, I don't care... But the evidence is all throughout science if one can let go of the religion of disbelief (or the attachment to emptiness, if you are Buddhist you'll get that). I am what I choose to be. I choose to be in love not in doubt. Nam Myoho Renge Kyo, and yes Jesus did love all of you. If you aren't thankful, well luckily, "He Loves Anyways" Peace. ps - check out Quantum Activist, and be pleasantly surprised, it's on Netflix instant.

ps - technically Big Bang theory is no longer the cutting edge. Even Expansion Theory is being replaced by new data. Just thought people should know that there are newer and more impressive and interesting theories. Also ever notice how close to Genesis BBT actually is? That's a form of Western Confirmation Bias, if you think about it much. ciao

Tony Mach #16:

Hmm, your interpretation of the evidence is at odds with that of 97% of the worlds publishing climate scientists. Not to make the argument from authority, but have you heard of the Dunning-Kruger effect?

For Tony Mach: in the hopes that you are willing to be honest with yourself, here's a link to the consensus argument for a sensitivity of 2 - 4.5 degrees C per doubling of CO2, with a most-likely value of 3 degrees: How sensitive is our climate?

George Bush: When he was Governor, I thought he was pretty capable. When he became President ... holy shit! I CHANGED MY MIND.

#22

This is the origin of the sign. First result that came up when I googled. :)

I assumed he was protesting against emphasizing the role of genetic drift rather than natural selection in determining the course of evolution.

I was with you up until the AGW.

Science by assocation, not by experiment.

I used to believe gun control would solve gun violence. Then I read the studies.

I have indeed seen this principle at work! When the Soviet Union collapsed due to the inherent foolishness of communism, the obvious question had to be asked: "If communism is so good, why did the Soviet Union collapse?" At the very moment of collapse, the explanation given was, and always is, "It wasn't true communism!" Since utopia exists only in the future, the collapse of a communist economy can never be admitted by the left--it's always and forevermore "not true communism". This also applies to socialism, too. I'm sure the collapsing socialist entities in Europe will soon be described as "not true socialism".

While agreeing that communism is a poor form of socioeconomic/political organization, I must point out that "the Soviet Union collapsed due to the inherent foolishness of communism" is out of line with the empirical evidence.

On topic for a thread such as this, I dare say.

And John Bailo: Perhaps you can show us how Tyndall's experiments were wrong, or how the observed top-of-atmosphere energy imbalance is false, or how the observed effects of greenhouse gases (by satellites at top-of-atmosphere and by other instruments at sea level) are false.

Just because I love Kepler, has anyone, or Ethan, read or seen The Sky's Dark Labyrinth, a fictional tale of Galileo and Kepler? I've just ordered it from Amazon. It's going to be a trilogy with the second book about Issac Newton and the third book about Hubble and Einstein.

Shifu: "obviously conscious-guided aspects of the evolutionary process"

I disagree with your entire post, but you have a right to believe what you'd like. However I would like to point out that using "obvious" is a poor way to get your point across. I don't care what you may think is obvious, I care about evidence and facts. What's obvious to you may not be obvious to anyone else.

Care to provide an example of 'obvious conscious-guided aspects'? I can think of many examples that are the complete opposite.

Man, I love this logic â the ridiculous argument that Dawkins would be reaching deep into the minds of the highly religious if only he would use different or better rhetoric. Hilarious. Better rhetoric as means to counter rhetoric! Perfect! Hubris as hubris killer!

This thread talks to the issue of graph development, of the structure that is a neuronal network and how its exact arrangement results in specific output. The issue is the cost of change. The true cost of novelty vs. the cost savings that is learned behavior. We all like to imagine our minds as perfectly plastic machines that morph and reform at the pace of evidence and logic and observation. But any computable structure, any signal/cypher system has to walk this thin and unforgiving line between cost of producing or editing a graph (high) and cost of navigating a pre-existing graph (relatively low).

It isn't or shouldn't be as surprise that a computing system would have trouble changing its computational behavior. The irony is that we should see an irony in any of this.

OK, let's back up. Let's talk computational theory: Is there a way to design a thinking device such that the process of running that device, of thinking on that devise, doesn't result in greater rigidity of expected output? In other words, isn't it true that there is simply no way to run a thinking device, to think, without restricting the kinds of thoughts possible in any subsequent cycles of thinking?

@ Randall Lee Reetz

Read Timothy Ferris' Coming of Age in the Milky Way for some interesting insights into the life of Johannes Kepler. He may have been brilliant, but he also had human failings, such as taking credit for other people's work.

Building a graph is orders of magnitude more expensive than navigating the same graph once built. Editing an existing graph is even more orders of magnetude more expensive still. This isn't debatable. The costal are resources including time. A graph built to learn always changes with each iterative cycle. Learning and graph building from scratch are mutually exclusive.

These comments are all 100% the opposite of Scott Adams intention. They overstate the 'before' and then cement in the 'after'. Anyone can do it, let me show you how easy it is. I am a right wing Christian zealot today. So I start by saying that when I was young I believed in live and let live, abortion is okay for you, thought porn was healthy, (on and on). Then when I stopped letting the dysfunctional mainstream feed me that garbage I came to realize the freedom in believing in a God and in Heaven. Now I reached peace and serenity like I've never known. This is all true. But I want to point out that everyone in here is full of crap if we are really saying we'd 'switch back' with the right kind of evidence. Baloney.

CD. I don't know how to begin. You're argument is a complet contradiction of your argument. A graph that can learn is a graph that becomes less and less flexible with each learning cycle. The bigger and more refined graph the more expensive is an edit to the structural layers of that graph. It doesn't matter should you like or if you not like this truth. A practiced graph is a less arbitrary graph and that always and necisarily means that it will have more and more expectable reactions to stimuli. That is the law of complex systems. You are believing what you want to believe despite the easy logic that defeats your position. A very good argument against the position you take.

Well let's start with the fundamentals then, Randall Lee Reetz. Creating a graph with N connections is actually no more computationally complex than traversing those same N connections. Taking an existing graph and changing it into a different graph is not necessarily more complex than creating that graph from scratch -- it only is if the old graph had substantially more connections than the new one and the connection-removal algorithm is O(connections) despite there being simple O(1) ways to do it. These are simple facts to demonstrate mathematically, indeed not debatable.

Learning algorithms may favour existing connections but it need not necessarily. Only making small changes from the existing graph is a design decision for cases where preventing regression is important (e.g. if it's considered worse to get a question wrong when we used to get it right than to get the new question right). That's not the only design decision. It's perfectly possible in a computational sense to not increase rigidity of a learning system as a necessary consequence of learning.

That doesn't mean it's necessarily practical to do so in a given situation. E.g. for our brains. This doesn't even mean such a system couldn't exist in reality; it could just be too big a jump from the local maximum our biological design is aiming at. If I seem to contradict myself maybe it's because this distinction wasn't clear but you said "computational theory" and "necessary" and that's just not mathematically true.

You seem to have a lot more invested in this emotionally than I do. Maybe you should ask yourself if you're not just believing what you want to believe.

@ Frank C

I've actually changed my position back and forth several times on right- vs left- wing, pro-life vs pro-choice.

While it's certainly true that at any given point in time I think my current position is "best" (that being why I changed to it), I am still open to future changes as, well, the historical evidence suggests that in the future I'll feel differently and look back at now saying "what was I thinking?".

There are also some positions I used to have that I'm sure I'll never hold again, but, well, it just seems the necessary reversals of facts on the ground are highly unlikely.

CB: The brain is nothing if not a "neural net". Computation, is infrastructure agnostic. Doesn't matter if your computer or brain uses ropes and pulleys, pipes and valves, levers and rods, cogs and spindles, transistors and wires, trained rats in shoots, RNA fragments in enzyme solution, isolated untangled quanta, or good old fashioned neurons, dendrites, and wandering phagocytes. But no matter how you construct your computer, the computational limits and opportunities you face will be identical and invariant. The only thing you can effect is the shape of the graph. Graphs are expensive to grow. Even more expensive to edit. And the least expensive thing you can do in a computer is navigate a graph that already exists. Given these computational absolutes, evolution and learning select for computational architectures that minimize graph building and graph editing and maximize graph navigation. In biological brains, this is more than obvious and necessary as neurons don't move much, aren't often created, and dendrites only grow at about one inch a week (and don't know where they are growing to). Radical changes of deeply rooted ideas or philosophies that support them are literally almost impossible to change. This is a physical fact. Any frustration directed at the all to human resistance to "changes of mind" is always a total waste of perfectly good frustration stock. The mind can swap "true" / "false" tags as applied to independent "facts" fairly easily. But an instantaneous change to the foundation of world view and belief and existential gestalt is as likely as a river jumping suddenly to the next revenue.

@Tony Mach: So you think we're doing big damage to the planet but you don't agree with taking measures that would require big hard work and sacrifice, right?

Tony: if you are asking (or rather, "telling") that question to me, I will respond by saying that desire and motivation can't change physics or causal reality. But should you care about effecting change, the best way to direct your energy is to understand and work rationally within the limits and parameters of the systems involved. That includes the system we call the brain. Tell me please how knowing how a tractor works should get in the way of plowing a field?

@ Randall Lee Reetz

The human brain is a *specific implementation* of a neural net. Generalizing the limitations of it to the underlying mathematics is unsupported. As are your statements about computational complexity. Traversing all edges of a graph with V vertices and E edges is O(E). Creating a graph with V vertices and E edges is O(E). Editing said graph into a new one with V' vertices and E' edges is O(E') if your edge deletion algorithm is O(1) which it should be. These are pretty trivial to prove. If you can prove that creating a graph is O(a^E) where a is a constant then feel free to show it but I bet I can optimize your algorithm into O(E).

Graph traversal is just as hard as graph creation, as far as computational theory goes. An example might be in order: Consider two chess algorithms that are identical except that one operates on a pre-computed tree of all possible game states (not a problem since our Turing Machine has an infinite memory tape), while the other one has to create said tree on the fly. Well, since creating a new game state from an existing state + performing one move can be done in constant time, two algorithms will differ in performance only by a multiplicative constant. Same big-O.

I don't know why it's so important to assume that the limitations of the human brain are inherent limitations of all thinking machines to the point of asserting mathematical un-truths. So you don't have to try to worry about overcoming them? So that you don't have to worry that we'll invent a thinking machine without these limitations and obsolete humanity? What?

"If communism is so good, why did the Soviet Union collapse?"

May as well ask if democracy is so good, why has the USA collapsed?

Or if capitalism is so good, why do we keep collapsing our economy based on it?

"I used to believe gun control would solve gun violence. Then I read the studies."

These would be studies where gun control reduced gun violence massively, right?

You see you DO NOT WANT gun control because you're a gun nut, therefore to ensure that gun control doesn't happen, you demand perfection in control before you'll accept it.

@ Wow

"May as well ask if democracy is so good, why has the USA collapsed?"

Not really since the Soviet Union really did collapse and the USA has yet to do so.

The last question is a rather good one that should be asked, though.

"Not really since the Soviet Union really did collapse and the USA has yet to do so."

Nope, it HAS collapsed. You have two right-wing branches of "choice", both beholden to the same clique. Democracy HAS died in the USA. Not just the USA, mind, but it HAS collapsed and did so at least 6 years ago.

NOTE: communism in Marxism was the other attempt to fix the inherent problems with capitalism: concentrating the power in the hands of the unaccountable "wealth generators" [NOTE: how similar this phrase is in Marxist theory to the rightwingnuts rhetoric to keep tax cuts for the rich...] by concentrating it in the hands of those who work for the state rather than themselves. That was known to be inherently wrong and then people would understand it isn't who is in power that's the problem: it's the concentration of power that is.

Um, that you believe "choice" should be in quotes as regards I'm assuming Presidential elections (I think you'd be much harder pressed to assert this is the case in all contests) is not even close to the same type of collapse that the Soviet Union underwent. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics no longer exists. It is fractured into many nations now.

When the United States is just a collection of States, no longer united under one government, then the situations will be comparable. Until then it's fair enough to say we lack adequate choice and power is too concentrated but inaccurate to say democracy has collapsed. Certainly not in the same sense as the Soviet Union.

//So let me ask you; what's your favorite example, from your own life, of when you changed your mind on an issue, based on the new evidence that you learned and couldn't ignore?//

That happened for me in regard to learning itself.

Before college, I was good at learning factual knowledge, but only with bits of knowledge. I learned what people told me, and I believed what people told me to be true, because they were my parents/teachers/pastors/etc.

In college, that changed - and the thing that sparked it was my introduction to astronomy course. Here, my professor took us to the roof, brought his own telescopes, and basically told us to have at the universe. He gave us some good places to start looking, and encouraged us to learn. Our course final was indeed part factual knowledge in form of an exam, but equally weighted was a project where he told us to pick a topic relating to astronomy (particularly something we covered in class, which as an introductory class was quite a bit) and write an extensive research paper on the topic. I decided to research and write about eclipses (many types). It was fascinating! It sparked my desire to not only learn about astronomy, but to learn about science in general. The more I read about eclipses, the more interested I became about other related topics... until those topics were no longer even tangentially related but altogether new topics. I couldn't stop wanting to learn!

That new desire to learn sparked something in me, and basically changed me as a person. I did a complete 180 degree turn from who I was to who I am now, and I could not be happier.

Perhaps the biggest "factual" change for me was the acceptance of the big bang / evolution based on facts (after MUCH research). The universe actually makes sense to me now. I can't get enough!

"Um, that you believe "choice" should be in quotes as regards I'm assuming Presidential elections"

Well, elections at the federal level, yes. Your state representative is no better, mind.

"not even close to the same type of collapse that the Soviet Union underwent."

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot???

The first bit is talking about the political collapse of democracy, the second is talking about the economic collapse of the USSR.

And the ECONOMIC collapse of the USA is as deep, nay, deeper, than that of the cold-war-era USSR. The only difference being that Russia didn't have the world currency, therefore couldn't get away with borrowing a trillion or three on the nod.