"The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars,

But in ourselves, that we are underlings." -W. Shakespeare

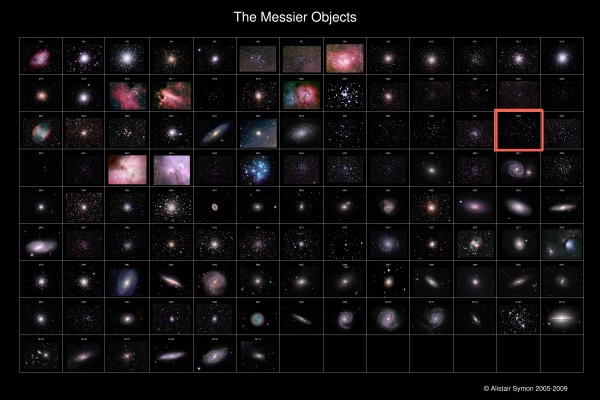

Welcome to just another Messier Monday here on Starts With A Bang! Each Monday, we're taking a detailed look at a different one of the 110 deep-sky objects that compose the Messier Catalogue, each one a different semi-permanent wonder of the night sky for our viewing pleasure here on Earth.

While we may not think of our galaxy as a hotbed of star formation -- and indeed it isn't compared to many, as it forms less than one Sun-like star per year on average -- that doesn't mean our galaxy isn't filled with newly-formed stars! These are found in the form of open star clusters, which is where new stars are primarily born. These clusters make up 33 out of Messier's 110 objects, outnumbered only by the galaxies. In fact, there are over 1,000 known open star clusters in our galaxy alone, with the true number often estimated to be as high as 100,000!

This week, we're going to spotlight Messier 38, an open star cluster in the constellation of Auriga. Here's how to find it.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Shortly after sunset, look towards the west and find the very bright star Capella, the third brightest star in the northern celestial hemisphere. (It's actually four stars: a pair of binaries orbiting each other!) Capella is the brightest star in the constellation of Auriga. A little farther down the horizon -- back towards the now-setting constellation of Orion -- you can find Alnath, another bright star on the border of Auriga and Taurus.

If you can spot Alnath in either binoculars or a telescope, you're well on your way to finding M38.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Alnath will appear as a bright blue star: the brightest object by far in your field of view. And if you move along an imaginary line back towards Capella, you'll find two orange-colored stars of about the same brightness as one another: φ Aur and σ Aur, both faintly visible to the naked eye. And if you look mid-way between these two stars and just slightly to the northeast of the imaginary line connecting them, you can't miss Messier 38.

Every open star cluster has a few things in common:

- It formed from a molecular cloud of gas and dust that underwent gravitational collapse,

- It formed a wide variety of star types, from the dimmest red-and-brown dwarf stars all the way up to hot, bright, short-lived blue stars,

- The hot stars' UV-radiation either burned off or is in the process of burning off the remaining gas-and-dust, and

- You can tell the age of the cluster by looking at the hottest, brightest stars that are still fusing hydrogen-into-helium in their core.

So, let's take a look at Messier 38 and see what we've got!

This, believe it or not, is the best professional image of Messier 38 out there, taken by the Digital Sky Survey 2. As you can tell, this cluster is full of bright blue stars with a smattering of red-and-yellow giants, and practically all of the nebular dust has long since evaporated. This is very likely what our very familiar Pleiades star cluster will look like in another 100-150 million years.

Image credit: © 2012 Jonathan Masin Astrophotography, via http://www.jemastrophoto.com/.

Image credit: © 2012 Jonathan Masin Astrophotography, via http://www.jemastrophoto.com/.

The brightest star in this cluster is a yellow giant -- easily visible above -- that's almost the same color but some 900 times intrinsically brighter than our Sun. Based on the evolution of stars in this cluster, it's probably about 220 million years old. This is around the time that most clusters that are this rich and densely packed begin to dissociate, so if you live another 220 million years, don't be surprised if it isn't around any longer!

With an estimated distance of 4,200 light-years, this cluster is pretty tightly packed, and is likely just 25 light years across. But unlike many of the open clusters, it doesn't appear to take on a spherical shape!

Image credit: © 2006 - 2012 by Siegfried Kohlert of http://www.astroimages.de/.

Image credit: © 2006 - 2012 by Siegfried Kohlert of http://www.astroimages.de/.

This cluster itself contains hundreds of stars at least, and possibly up into the low thousands if we were to probe it deeply enough. At this point -- at a distance of 4,200 light-years -- those observations simply haven't been made yet!

I would estimate -- based on the deep image above -- that 1,000 is a reasonable estimate for what lies in here.

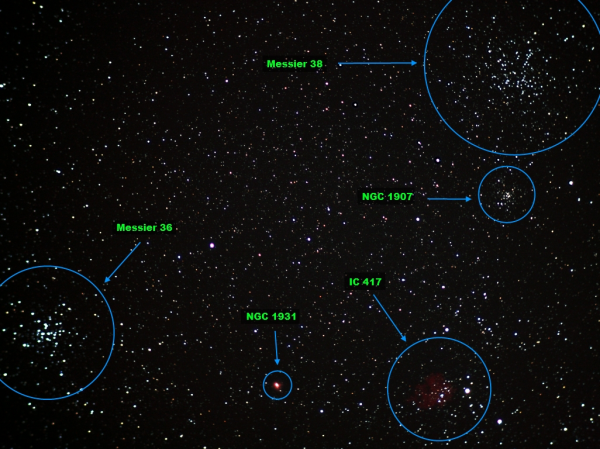

But what's perhaps most interesting about Messier 38 is that it's not at all alone in the sky, something that's immediately apparent if you look at a wider-field image.

Image credit: RoryG of Eastex Astronomy, via http://eastexastronomy.blogspot.com/.

Image credit: RoryG of Eastex Astronomy, via http://eastexastronomy.blogspot.com/.

There's another open cluster -- smaller and fainter -- very, very close by: NGC 1907. You wouldn't be out of place at all to wonder if these two star clusters were related; after all, there are well-known molecular clouds that are huge and expansive, and result in the formation of many open clusters over time.

In fact, if you thought that, you might think to expose a special filter -- looking for a characteristic emission line of hydrogen -- to see evidence of a molecular cloud complex nearby.

Image credit: Stuart Heggie of http://www.astrofoto.ca/stuartheggie/.

Image credit: Stuart Heggie of http://www.astrofoto.ca/stuartheggie/.

There is, in fact, some gas there! So you might think to look to an even wider field, and see if there are other clusters lying around.

Guess what: there are!

So you look at this and conclude that:

- A.) These clusters are all related to each other, forming out of the remnant of the same ancient molecular cloud, or

- B.) The Universe is conspiring to trick you, and Messier 38 is completely unrelated to all these other objects.

So we've measured these distances, and they're all somewhere between 3,500 and 5,000 light-years distant. So option A it is, right?

Image credit: © 2010 - 2013 Dean Jacobsen of http://www.astrophoto.net/.

Image credit: © 2010 - 2013 Dean Jacobsen of http://www.astrophoto.net/.

Ha, ha, no way! The Universe tricked us again; it's totally B! The key is to look at the ages of these clusters, because stars don't lie! NGC 1907 is more than twice as old as Messier 38, at some 500 million years, while Messier 36 is far younger, at just 25 million years! It's also not related to the (relatively close by) Messier 37, if you were wondering about that, too. But there is a fun, distinctive marking in this cluster that makes it unique, particularly through a small telescope.

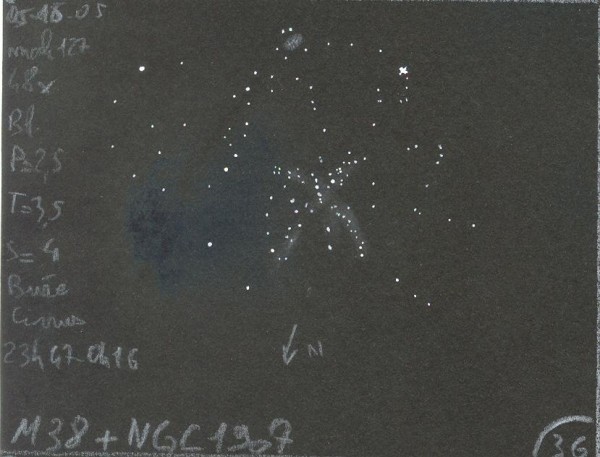

Image credit: User Mad-Mak (Boris Emeriau) of http://www.astrosurf.com/mad-mak/.

Image credit: User Mad-Mak (Boris Emeriau) of http://www.astrosurf.com/mad-mak/.

It has a shape that's either described as a cross, or, for the more mathematically inclined, a Greek Pi!

And that’s all for another Messier Monday! Including today, we’ve taken a look at the following Messier objects:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

Come back next week, where we’ll take a detailed look at one of the real molecular cloud complexes that are found among Messier’s 110 deep-sky objects, only here on Starts With A Bang’s Messier Monday!

Ethan,

All of these Messier columns are excellent introductions to the objects and instill an appreciation for each that whets one's appetite for digging deeper. Thank you!

Bernie