"If it's true that our species is alone in the universe, then I'd have to say the universe aimed rather low and settled for very little." -George Carlin

Whatever you may think of the chances are for intelligent life in our galaxy are today, I can guarantee you they're going to go up dramatically in a few billion years. Sure, by that time the Earth may be a little too hot for comfort, and in that sense -- as Split Lip Rayfield would say -- we'll probably

But that doesn't mean there won't be a new-and-improved home out there, not only from among the stars and planets in our own galaxy, but from the ones in our closer, larger neighbor, Andromeda!

Image credit: Christopher Madson, user mads0100 of astrobin, via http://www.astrobin.com/54638/.

Image credit: Christopher Madson, user mads0100 of astrobin, via http://www.astrobin.com/54638/.

Over the next few billion years, our galactic big sister will continue to approach us, eventually merging with us and combining into -- most probably -- a giant elliptical galaxy.

What's remarkable about this is that by time this merger takes place in the far future, a star-and-planet born today in Andromeda will have the potential to be Earth-like by then! So when we look at the young star clusters there today, these could be the future homes of civilizations like our own, or potentially colonizable and inhabitable worlds for human-like creatures.

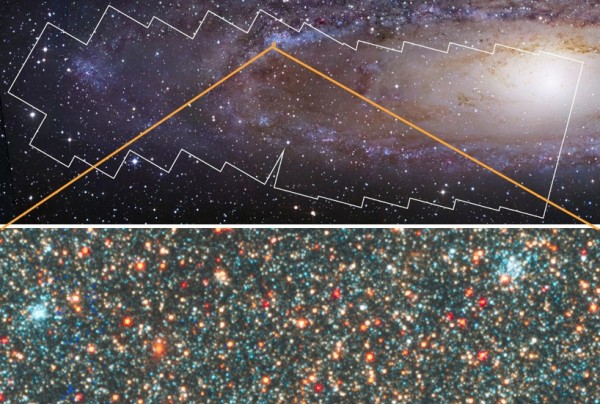

And just like we have star clusters in our own galaxy (and background galaxies behind our galaxy's stars), so does Andromeda. In the outer reaches of Andromeda (as seen in stunning resolution in the Hubble image, below), you can easily pick out background galaxies and star clusters.

But what about in the inner reaches of Andromeda?

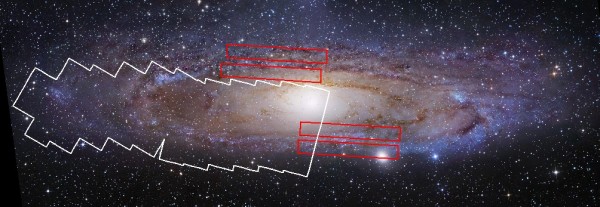

It turns out the data is there, but it's far too massive an undertaking for a team of scientists, and yet far too difficult an undertaking for artificial intelligence. After all, this is how much of Andromeda has been imaged by Hubble:

Image credit: Robert Gendler via the Andromeda Project blog, http://blog.andromedaproject.org/.

Image credit: Robert Gendler via the Andromeda Project blog, http://blog.andromedaproject.org/.

And this is what a tiny, tiny fraction of the Andromeda galaxy is encapsulated by a single Hubble image. Note the two prominent open star clusters in there.

So that's the level-of-detail necessary to identify star clusters in our nearest-neighbor galaxy.

Well, it might be too big a task for a few dozen scientists and too smart of a task for a machine, but that's what citizen science is all about, and so I'm pleased to introduce you to The Andromeda Project!

Image credit: Robert Gendler (of Andromeda); screenshot from http://www.andromedaproject.org/.

Image credit: Robert Gendler (of Andromeda); screenshot from http://www.andromedaproject.org/.

You can sign up and log in, or simply start classifying objects! When you begin, you'll be presented with a tutorial, but I'd like to prep you anyway.

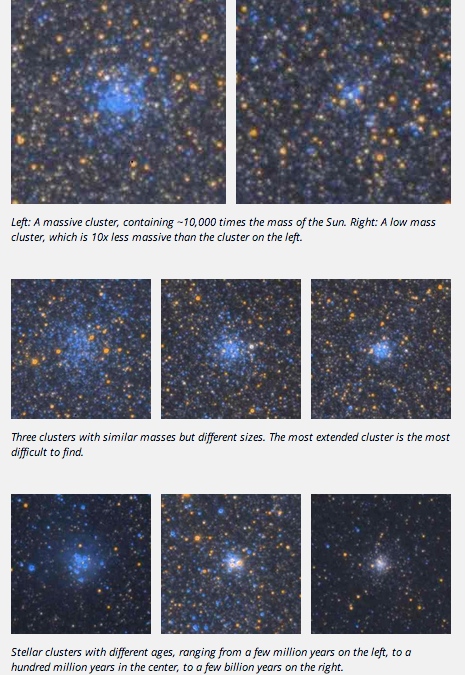

Here's what you're looking for.

First off, the most common actual thing you'll find are star clusters, which can be blue, white or orange in these images, and can be bright and prominent or dim and faint, barely visible against the other stars in the plane of Andromeda.

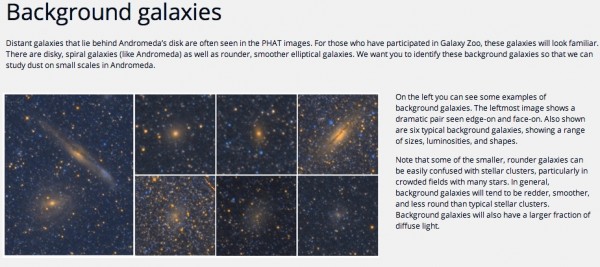

There are also background galaxies, which is always a treat for me when one shows up!

These are often faint, diffuse and orange, and unlike star clusters cannot be resolved into individual points-of-light.

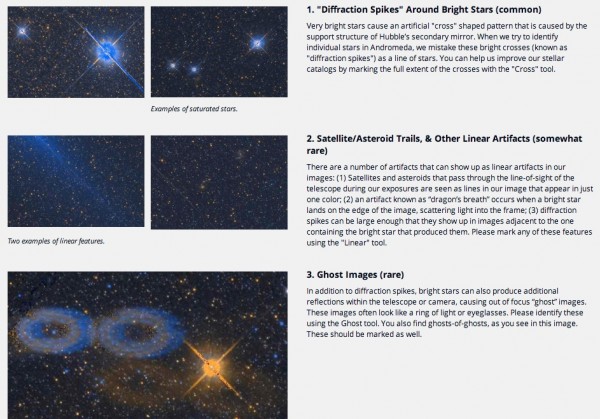

And finally, there are artifacts that contaminate the images. While cosmic rays (blue or orange streaky lines) and edge-of-field effects aren't things that you should mark, diffraction spikes (from foreground, Milky Way stars) and the rarer satellite trails and ghost images (which I haven't seen any of, yet) are important to identify.

And while there are some images that won't have anything of interest at all, most of them have at least one interesting thing. Don't be discouraged if you aren't sure how to mark something; I'm absolutely positive that's a difficulty we all share!

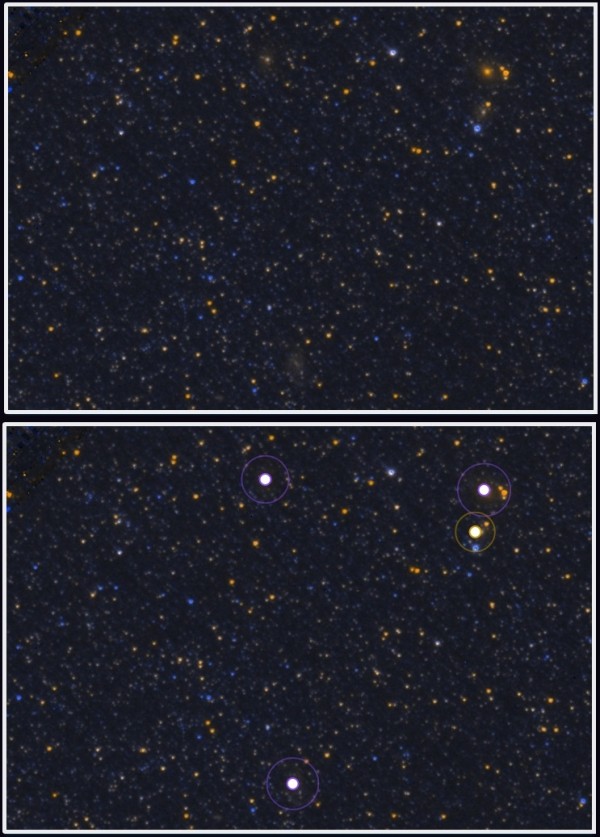

Here, have a look at an image I came across, and see what you would've done?

I said there were three galaxies and one star cluster, although I'm not sure even now whether that's correct.

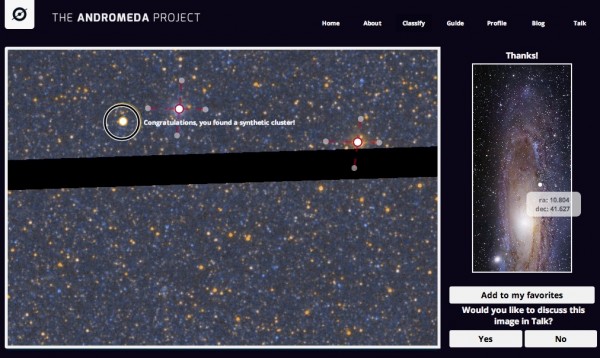

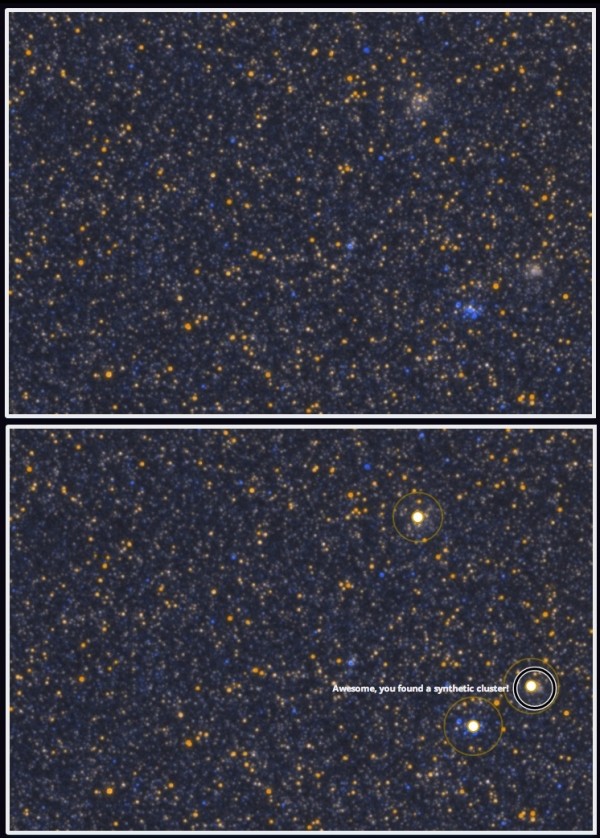

Sometimes, when you find a star cluster, you'll get a message like this:

A synthetic cluster? Believe it or not, this is brilliant! The team inserted fake star clusters of varying colors and brightnesses to make a control to see how good people are at identifying clusters. of different properties. When you find a synthetic cluster, it's surefire confirmation that you're finding something you're supposed to find!

But don't stop at just one; sometimes synthetic cluster and real clusters can show up alongside one another.

Did I miss a small one just to the right-of-center in the image above? Maybe, and that's okay. Don't worry if you get something wrong; plenty of people do and that's taken into account!

The key is that there are many, many eyes on each of these images, and on average we're good at getting it right. This is actually phase II of the Andromeda Project, and results from phase I can give you some indication of how the general public is doing. Check it out!

Great idea and article here, stunning images. Cheers. :-)

I have participated in this and it is highly interesting for several reasons. First - I enjoy perusing the images. And second- it is precisely the same process that I use in my own professional work. I am a radiologist and my day is spent searching for abnormalities on various types of images - usually breasts - mammograms, ultrasounds, and MR scans. I want to point out that anyone who participates in the andromeda project will experience the internal dialog ('is that REALLY something? Should I mark it?) that we radiologists go through thousands of times a day. The anxiety about false negatives and false positives is always there. In this way, non-radiologists can get an idea of how difficult image interpretation actually is, vs the way it is usually discussed among lay people ("my mammogram was negative" - implying a 100% certainty).The andromeda project is something that the informed lay person can participate in without the years of training we go through.

I would be interested to know what they might have tried in the way of computer recognition. In our neck of the woods, it is called Computer Aided Diagnosis (CAD), and is used nearly universally for mammograms, and is starting to be used for some CT scans. It will mark areas of some suspicion for further analysis by the radiologist, in this way hopefully avoiding some false negatives. It will mark on average between 3-7 places on each case (you can set the sensitivity), so that in a thousand cases, you will have 3000 - 7000 marks to wade through, and among these will be about 4 cancers.

a couple of other things.

You can read more about the results of the initial part of the project here:

http://blog.andromedaproject.org

and see the poster that was presented at the AAS here:

http://www.astro.washington.edu/users/lcjohnso/andromedaproj_aas2013.pdf

They note that the project was completed in a month, with "citizen scientists" viewing more than 1,000,000,000 images in that time.

I've read that the collision or intersection of two galaxies can produce gravitational interactions between stars that can fling a star out of a galaxy entirely. If this is correct, what range of speeds would be expected for stars that are ejected by galaxies in this way, relative to the movement of the galaxy from which they were ejected?

--

Hopefully by the time that Andromeda and the Milky Way collide, we or post-we are spread out across numerous star systems, with the technology to do interstellar trips at a low two-digit percentage of c.

By that time, we will have found numerous other planets with indigenous life on them, and probably at least one other technologically-capable civilization. We will have a pretty good idea of the range of life that exists in the Milky Way. But we won't, until that point, have had any way to explore star systems in other galaxies.

The question is, does life work the same way in other galaxies as in our own? The collision with Andromeda will give us the chance to find out, by tracking incoming stars and then searching for life-bearing planets around them. Missions sent to those systems would find the biological data to answer this question.

These types of projects would take thousands, possibly tens of thousands of years, even for an advanced civilization. But if we've passed the cosmic Darwin test of interstellar migration, we'll have the long span ahead of us to explore and discover on many fronts that appear unimaginable today.

I join to the project with USM www.kanevuniverse.com

Fantastic article, great work bringing attention to citizen science.

And thanks for featuring my Andromeda image Ethan!

- Adam

www.flickr.com/astroporn

www.sky-candy.ca