"I don't watch it, but I know enough to comment on it." -Dan Quayle

First off, I want to thank everyone involved here at Scienceblogs (especially Wes Dodson) for all the support over the years and especially over the past few months, even as the main Starts With A Bang blog has moved to Medium. I think it's important to keep this place open as a home for comments and discussions, and it's my great hope that excellent ones continue to ensue here.

Well, they have so far, particularly on three posts from the past week:

As part of a new series unique to Scienceblogs and the commenters here, let me call out (and respond to) my favorite ones!

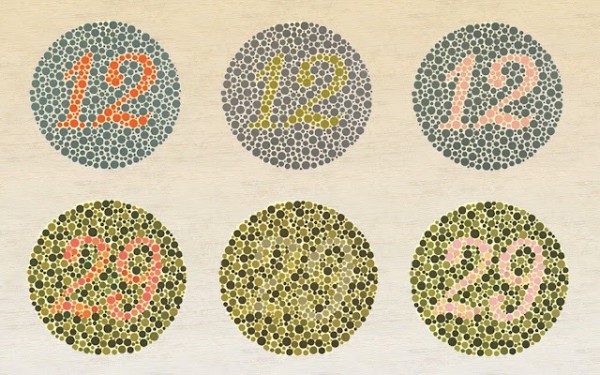

"I find that lower middle “29″ hard to see. What sort of color-blindness does that denote?" -eric on What is color?

The image to which eric refers is this:

Image credit: Sabrina Bresciani of http://sabrinabresciani.com/2012/09/04/testing-your-skills-in-color-vis….

Image credit: Sabrina Bresciani of http://sabrinabresciani.com/2012/09/04/testing-your-skills-in-color-vis….

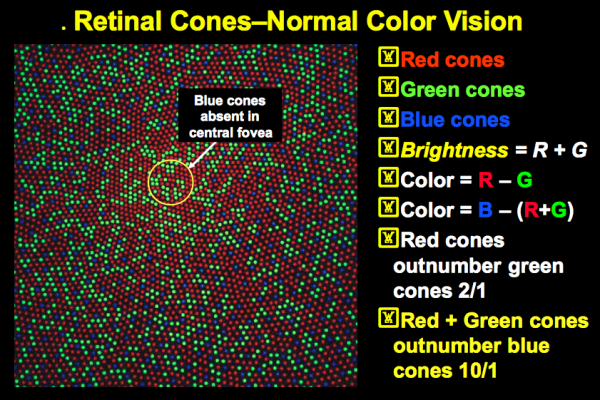

For most people with color blindness, they have either the red or green cones absent or have the wavelength of their sensitivities shifted. Normally, the cones are distributed on your retina as follows, and allows your brain to interpret the different signals as the different colors you perceive:

I believe that the middle column -- both the top and bottom rows -- show numbers that are invisible to the population that's missing the green cone altogether. But if it's just difficult to see the 29, you're normal; it's difficult for me as well and I'm not colorblind.

"To challenge scientists to explain a simple question to 11-year-olds in less than 300 words, what is that a challenge?" -Chaeremon on What is Color?

You might have missed why this is a challenge, why this is important, or how necessary this is. So I'll let Alan Alda -- the issuer of the challenge himself -- explain.

"Just imagine, if the Universe were not full of photons, we would not be aware of our environment by visual means." -PJ on Ask Ethan #26: Burn, Baby, Burn!

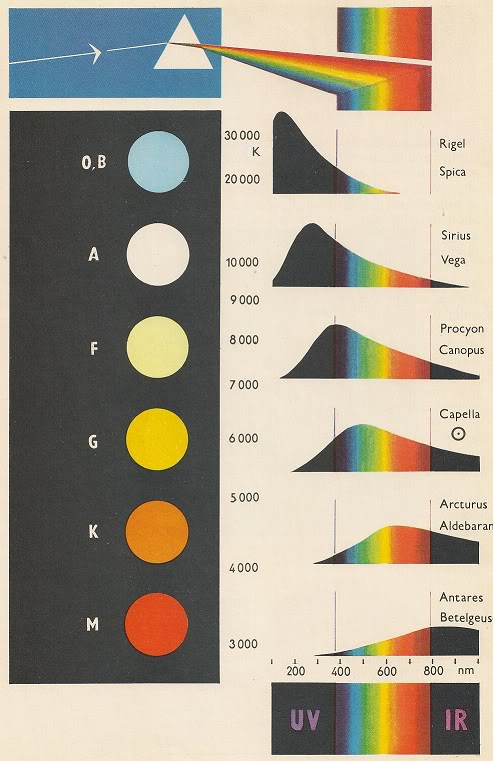

This might seem like a tautology, but in fact it's a much more astute observation than it might appear at first glance. You see, what we consider "visual means" is only because our eyes are suitably adapted to see the light that comes from our star, which just happens to be very useful for seeing the light from pretty much all types of stars in the Universe. But it didn't need to be this way.

Image credit: a scan via user Stonebridge of Physics forums, via http://i57.photobucket.com/albums/g220/DrNebula/stellar.jpg.

Image credit: a scan via user Stonebridge of Physics forums, via http://i57.photobucket.com/albums/g220/DrNebula/stellar.jpg.

If we were born around a much bluer star and were sensitive to mostly ultraviolet light, red giant stars would be invisible to us. Conversely, if we were born around an M-class star and were sensitive to mostly infrared light, the brightest, bluest stars in the sky (like Sirius, Vega and Rigel) would appear far less prominent to our eyes. We're adapted to the photons we are because of the light emitted by our Sun, but if we had a different parent star, our visual awareness would likely be awfully different!

"I think you should keep global warming out of your blogs Ethan. It isn’t cosmology. When Phil Plait does it, it comes over as preaching and screeching. Painful." -John Duffied on Can science ever be "settled"?

Of course, my expertise is in cosmology. Specifically, in large-scale structure formation, in early Universe physics, and in dark sector cosmology. Does that mean that I should stay out of the other aspects of cosmology, and let the other scientists out there who do specialize in those fields discuss them? Does it mean that I should cease writing about other areas of physics -- like high-energy/particle physics -- because other people out there have a greater expertise than I do? Does it mean I should never write about chemistry, biology, geoscience or any other aspects of science?

You may think so; no one is compelling you to read what I'm creating. But let me explain something to you about cosmology, and why it's been so valuable to me personally.

In order to be good at cosmology, you need a very strong understanding of a great many different aspects of the physical Universe. You need to have an expert-level understanding of gravitation, in nuclear physics and nucleosynthesis, in atomic physics, in quantum mechanics, in classical and quantum field theory, in thermodynamics and statistical physics, and then some. I was fortunate enough to get a very deep education, but also a very broad education, and to understand not only the limits of my own knowledge, but who and where to turn when I want to understand what is known that's beyond my own knowledge.

You may not respect my knowledge or abilities to do just that, but people in their fields that I respect -- experts in their own right -- consistently tell me that I've represented their science accurately, and are happy to correct me on my mistakes for the next time. It may seem trite to say, but the truth is that I'd be willing to bet I've learned more than anyone reading my blog about science from the writing I've done, and the research necessary to do it.

"The thing is that any new scientific theory also has to explain 100% of the things that the thing it replaces was able to explain. Relativity is a great example of that. It replaced Newton’s laws and did so by precisely mimicking the results of Newton’s laws at all but the very highest speeds and gravitational fields. The only areas where it replaced it were areas that had not been adequately tested experimentally, such as the way light bends around a star.

So, you can’t say that global warming is replaced by some new theory unless that theory also explains why the earth is warming and why it’s so closely correlated with the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Hence any replacement theory isn’t likely to say that we don’t have to worry about burning coal anymore.

It’s a similar deal with evolution – sure, there are things we’re learning about the way inheritance works that suggests that Lamarkism is not entirely wrong – but this new variation on evolution can’t just say “God Did It” because that’s inconsistent with the discoveries and experiments that we already know are true. The modified theory still has to show that humans still descended from apes because that’s what the experimental evidence clearly demonstrates.

So, yeah – science may never be 100% settled – 100% true – but each change to an existing theory is going to be a smaller and smaller tweak resulting in less and less difference between what the new theory predicts and what the old one so successfully laid out." -Steve Baker on Can science ever be "settled"?

This was just a very good comment to me. I wanted to call it out and share it with you if you hadn't come across it on your own.

"Perhaps settled should just be dropped from the vocabulary? It worked when my father told me something was settled, and my father was a great scientist, but he never used it in the same sentence with science. Another term that should be dropped is consensus, natural laws are never subject to a vote." -Jerry on Can science ever be "settled"?

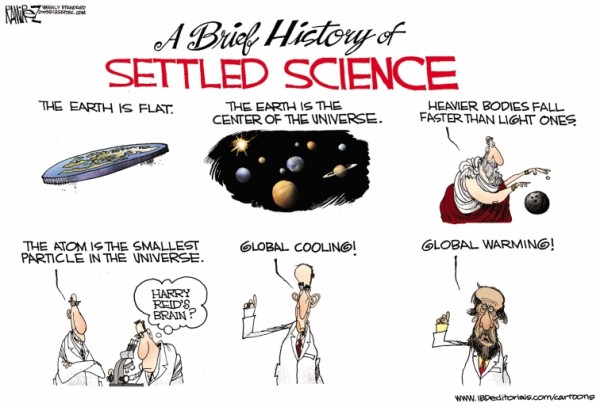

This underlies an inherent difficulty in communicating science to the general public, or communicating anything to anyone in general. Is it possible -- if someone has a preconception that's different from the truth -- to get them to engage at all? And if so, what's the best approach to making that a reality? After all, I didn't agree with this image, but I posted it because, well, it exists, and the audience that does agree with it is part of the audience I wanted to engage.

Image credit: Ramirez of the Weekly Standard, via http://www.IBDeditorials.com/cartoons.

Image credit: Ramirez of the Weekly Standard, via http://www.IBDeditorials.com/cartoons.

It's not an easy question, and I'm not sure there's a universal answer, or even an answer in many cases. But I think it's a mistake to ignore the words and arguments people are using. If millions of people are using the word "settled" and it's your goal to engage (at least some of) them, I don't think it does any good to pretend that no one's ever said that word. There are plenty of words that scientists used that the general public uses with a different meaning (e.g., theory), but that doesn't mean we need to stop using those words; it means we need to do a better job of making sure the scientific truth behind it comes out.

Thanks for your great comments this week, and I'm looking forward to the great ones that will come out in the coming ones!

" Is it possible — if someone has a preconception that’s different from the truth — to get them to engage at all? And if so, what’s the best approach to making that a reality?"

I think the answer to this depends on whether that "someone" has a worldview that supports science, or if science supports their worldview.

I've been reading about the "back-fire effect" lately, and it has reinforced my strong anecdotal evidence about the folly of arguing with anyone who is attached to their position.

Thanks for answering mine! I was pretty sure I wasn't colorblind (too old for it not to have come up earlier), but I was indeed looking for a mechanistic explanation associated with seeing that figure, and you provided it.

Stop by SWAB & tell them crd2 sent you for a free eye exam!

To bad the "Spider Webs… on drugs?" piece wasn't posted in the ".. Bang" blog where the faithful can still visit and comment.

I have many ruminations on spiders having watched them for decades along with my very observant cats. My wife and I will often relocate the arachnids to more beneficial locations within the house. I have a garage fully inhabited by Brown Recluses that I coexist with, often barefooted and shirtless in the summertime. (me, not them). Recluses also make up a good percentage of our in-house population.

You are also probably more likely to be in a car wreck than be bitten by a spider. They DON"T bite people in bed as so often espoused. Those are other bugs you have in your bedroom. Not many spiders can even open their chelicerae wide enough to bite human flesh.

And I wish they wouldn't waste mescaline sulfate on a spider. They can't appreciate it's benefits like more sentient beings can.

I don't think that the color of the star has as much to do with the colors our eyes have adapted to see as much as the colors that reflect the best from surfaces. Once you start getting too far beyond UV or IR things get fuzzy and shapes are not nearly as defined.

So, you can’t say that global warming is replaced by some new theory unless that theory also explains why the earth is warming and why it’s so closely correlated with the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere.

I think that most people who fashion themselves to be denier slayers assume that the deniers are in full denial of every aspect of the theory. Sure some kooks think that CO2 isn't a greenhouse gas, but they are few and far between, and they are marginalized by the majority of deniers as well. The fact is that there is a wide continuum of opinions that range from the kooky to the plausible. But it all comes down future predictions. The denier slayers contend that they see a very bleak future for humankind and the planet Earth while deniers generally say let's not be too hasty with these sweeping changes to the economy. Well, that's what really rankles the denier slayers, not that the deniers quibble with how much climate changed in the past or the mechanism by which it did. That's all academic. No, they don't predict the same future that the slayers see, a future that requires the very sweeping changes to everybody's lives that they themselves prescribe. Anyone who doesn't agree with their grand vision is a climate holocaust denier, nay an enabler.

"but they are few and far between, and they are marginalized by the majority of deniers as well. "

You are living in a fantasy world when you say that. denialists welcome one and all into their tent of ignorance.