Lab Stories

I spent the last few days in Ontario, attending the Convergence meeting at the Perimeter Institute. This brought a bunch of Perimeter alumni and other big names together for a series of talks and discussions about the current state and future course of physics.

My role at this was basically to impersonate a journalist, and I had a MEDIA credential to prove it. I did a series of posts at Forbes about different aspects of the meeting:

-- The Laser Cavity was Flooded: a revisiting of the idea of True Lab Stories, which was a loose series of funny disaster tales from the early days of…

One thing I left out of the making-of story about the squeezed state BEC paper last week happened a while after publication-- a few months to a year later. I don't quite recall when it was-- I vaguely think I was still at Yale, but I could be misremembering. It's kind of amusing, in an exceedingly geeky way, so I'll share it, though it's also a story of an embarrassing mis-step on my part.

So, the physical situation we were studying is described by the "Bose-Hubbard Hamiltonian": Bose because it's dealing with bosons (there's also a Fermi-Hubbard version, I believe); Hubbard after [mumble]…

Yesterday's write-up of my Science paper ended with a vague promise to deal some inside information about the experiment. So, here are some anecdotes that you would need to have been at Yale in 1999-2000 to pick up. We'll stick with the Q&A format for this, because why not?

Why don't we start with some background? How did you get involved in this project, anyway? I finished my Ph.D. work at NIST in early 1999, graduating at the end of May. I needed something to do after that, so I started looking for a post-doc by the don't-try-this-at-home method of emailing a half-dozen people I knew…

Over at Unqualified Offerings, Thoreau proposes an an experimental test of Murphy's Law using the lottery. While amusing, it's ultimately flawed-- Murphy's Law is something of the form:

Anything that can go wrong, will.

Accordingly, it can only properly be applied to situations in which there is a reasonable expectation of success, unless something goes wrong. The odds of winning the lottery are sufficiently low that Murphy's Law doesn't come into play-- you have no reasonable expectation of picking the winning lottery numbers, so there's no need for anything to "go wrong" in order for you…

Before leaving Austin on Friday, I had lunch with a former student who is currently a graduate student at the University of Texas, working in an experimental AMO physics lab. I got the tour before lunch-- I'm a sucker for lab tours-- and things were pretty quiet, as they had recently suffered a catastrophic failure of a part of their apparatus.

Of course, there are catastrophic failures, and then there are catastrophic failures. Some dramatic equipment failures, like the incredible exploding MOSFET's when I was a post-doc, are just God's way of telling you to go home and get a good night's…

One of my pet peeves about physics as perceived by the public and presented in the media is the way that everyone assumes that all physicists are theoretical particle physicists. Matt Springer points out another example of this, in this New Scientist article about the opening panel at the Quantum to Cosmos Festival. The panel asks the question "What keeps you up at night?" and as Matt explains in detail most of the answers are pretty far removed from the concerns of the majority of physicists.

But it's a good question even for low-energy experimentalists like myself, as it highlights the…

In the time that I've been at Union, I have suffered a number of lab disasters. I've had lasers killed in freak power outages. I've had lasers die because of odd electrical issues. My lab has flooded not once, not twice, but three different times. I've had equipment damaged by idiot contractors, and I've had week-long setbacks because the temperature of the room slews by ten degrees or more when they switch the heat on in the fall and off in the spring. I had a diode laser system trashed because of a crack in the insulation on a water pipe, that exposed the pipe to moist room air, leading to…

Dave Ng has recently upgraded the Order of the Science Scouts of Exemplary Repute and Above Average Physique site, which provides a variety of achievement badges for members to claim and post. I'm not a big one for extra graphics on the blog (they delay the loading of the cute baby pictures), but if you're into goofy stuff, they've got some fun options.

For the record, the badges I can claim include:

I Blog About Science (duh)

Has Frozen Stuff Just to See What Happens (Level III) (liquid nitrogen is cool)

Worship Me, I've Published in Nature or Science

Experienced with Electrical Shock (…

Over the past several weeks, I've written up ResearchBlogging posts on each of the papers I helped write in graduate school. Each paper write-up was accompanied by a "Making of" article, giving a bit more detail about how the experiments came to be, what my role in them was, and whatever funny anecdotes I can think of about the experiment.

If you haven't been following the series, or would just like a convenient index of the posts, here's the complete set:

Introduction and explanation of metastable xenon.

Experiment 1: Optical Control of Ultracold Collisions and the making thereof.…

As mentioned in the previous post, the cold plasma experiment was the last of the metastable xenon papers that I'm an author on. My role in these experiments was pretty limited, as I was wrapping things up and writing my thesis when the experiments were going on.

The main authors on this were Tom Killian, now running his own cold plasma lab at Rice and Scott Bergeson, now running his own cold plasma lab at BYU. Scott was a pulsed-laser expert with a remarkably cavalier attitude toward things like anti-reflection coatings on vacuum windows, and Tom came from Dan Kleppner's hydrogen BEC project…

This was the last of the experiments that I did for my thesis (it's not the last xenon paper I'm an author on, but the work for that one was done while I was writing up), so my memories of it are bound up with the thesis-writing process.

My favorite story about this stuff was when I gave a talk about this work at NIST-- I don't recall if it was before or after my defense-- and somebody asked the obvious question about how the quantum statistical rules are enforced. That is, how is it that you never get two identical fermions colliding in an s-wave state? Since an s-wave collision is just a…

As I said in the introduction to the previous post, this was the first paper on which I was the lead author, and it may be my favorite paper of my career to date. I had a terrific time with it, and it led to enough good stories that I'm going to split the making-of part into two posts.

The experiment itself was based on an earlier paper by Phil Gould at UConn. Phil was a post-doc at NIST back in the day, and used to visit our group fairly regularly. On one of these visits, he stopped by the xenon lab, and gave me a pre-print of their time-resolved collision paper, saying "You guys really…

This paper is the third of the articles I wrote when I was a grad student, and the first one where I was the lead author. It's also probably my favorite of the lot, not just because of the role it played in my career, but because it packs a lot of science into four pages.

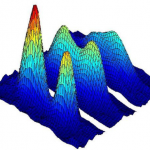

The whole thing is summarized in this figure from the old NIST web page, which is a simplified version of Figure 2 from the paper itself:

This shows the collision rate as a function of time after we hit a cold sample of atoms with a 40ns pulse of laser light tuned near the atomic resonance frequency. As discussed in the…

One of the things I'd like to accomplish with the current series of posts is to give a little insight into what it's like to do science. This should probably seem familiar to those readers who are experimental scientists, but might be new to those who aren't. I think that this is one of the most useful things that science blogs can do-- to help make clear that science is a human activity like anything else, with its ups and downs, good days and bad.

To that end, I'm going to follow the detailed technical explanation of each of these papers with a post relating whatever anecdotes I can think…

I've been slacking a bit, lately, in terms of putting science-related content on the blog. Up until last week, most of my physics-explaining energy was going into working on the book, and on top of that, I've been a little preoccupied with planning for the arrival of FutureBaby.

I'd like to push things back in the direction of actual science blogging, so I'm going to implement an idea I had a while back: I'm going to go back through the papers in my CV, and write them up for ResearchBlogging.org.

This offers a couple of nice benefits from my perspective. First of all, I already know what's in…

Typing up the demolition story reminded me of another before-my-time NIST story. Again, the statute of limitations has run, so it's probably safe to tell this.

As mentioned in the earlier post, it was very expensive to get the official facilities team at NIST to do construction work, so a lot of things used to be done on the cheap by people in the research group. Most of this was fairly harmless, but it occasionally got taken to extremes.

The worst example I know of had to do with a laser that the group acquired. Large-frame lasers draw rather a lot of power, and so usually require dedicated…

This is actually sort of a pre-lab story, as it happened before my lab in grad school was even established. It pre-dates my time at NIST, and happened long enough ago that the statute of limitations has surely run out, so I feel safe telling it.

The lab I worked in in grad school was acquired by the group a couple of years before I got there. It had previously been used by a group doing something involving wet chemisty, so there were lots of benches and sinks and other things that we didn't need or want in a laser lab.

They brought in the NIST facilities crew, and asked them how much it would…

It's been a while since I did one of these (see "How to Tell a True Lab Story" for an explanation), but yesterday's laser tech story reminded me of one.

The lab next to mine in grad school also used an argon ion laser to pump another laser, but they were much more cramped for table space than we were. Instead of putting the argon ion laser (which was about 6' long) on top of the table, they put it on a bench that slid under the optical table, then used mirrors to direct the beam up onto the table top. Since the ion laser is pretty much a black box, this worked great, and they could drag it…

Every now and then, usually in the summer or early fall, when the sun is shining and it's just pleasant to be outdoors, I find myself almost regretting my career choices. After all, had I chosen a career in the biological sciences, rather than laser physics, I could do my research outside in the nice weather, rather than in a windowless room in the basement.

Of course, every now and then, I hear stories like the one in the talk given by a colleague's summer research students a few weeks ago. He's a plant biologist specializing in moss, and his students went out looking for samples to test…

A week or two ago, one of my students measured the power output of a grating-locked diode laser, and came into my office saying "I think I may have killed the laser." The power output was much too low for a laser of that type, which is a bad sign.

So, we went down to the lab, and looked at the system, and after a minute, I said "Rotate the laser ninety degrees in its mount, and measure it again."

And, lo, the power was back up at the level we expected originally.

As I explained to my student, this wasn't actually black magic, just physics that I knew and he didn't. The light coming out of…