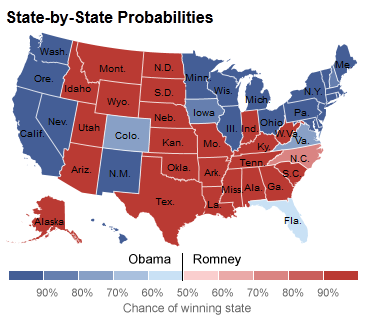

If you're one of the probably four people who haven't heard about Nate Silver, you've missed out. He's a statistics guy who runs the always interesting 538 Blog at the New York Times. He made his name in baseball statistics, Moneyball style, and moved into politics where he made state-by-state statistical forecasts of the last couple national elections. His track record is pretty good. The final prediction for this election was an Obama win with 90.9% probability, and it duly came to pass. On a state-by-state basis, he seems to have been correct in every case. (Much of this was blind luck, as he'd be the first to tell you. His model yielded coin flips in a few cases like Florida, and the fact that his 50.3% chance there happened to come out right was a matter of good fortune.)

So I like the guy a lot, and his Monte Carlo methods are near and dear to me and pretty much any physicist who's ever done a computationally-intensive calculation. But I do want to be the guy who sounds the sad trombone and pours just a little cold water on his well-deserved celebration, for two reasons.

1. It's not science.

Well, it might be. We can't tell. His model is closed. He hits the go button on his computer, it spits out numbers according to some algorithm that isn't public, and they tend to be right most of the time. That suggests that he's doing something right. But science has to be testable, and while and accurate prediction is a test, it doesn't advance our understanding of the world unless we know just what it is we're testing.

Which isn't to say he's under any obligation whatsoever to make his algorithm public. If I ever discover an algorithm that can predict the stock market with uncanny accuracy, I'm certainly not going to tell any of you how it works. It won't be science, and because I love science I'll just have to console myself with a fruity drink beside my gigantic pool. While I doubt a presidential prediction model is so lucrative, he's perfectly justified in keeping it to himself if he wants.

2. It's not necessarily an improvement on simpler methods.

If you had just made a prediction based on the average of each swing state poll over the last week or so, you'd have probably made the same call in every case except Florida. Are further refinements to that simple "take the polls at face value" model actually improvements, or just epicycles? Beats me, but the answer is not obvious.

These two objections are pretty minor in the grand scheme of things, and I reiterate that I'm a big fan of statistical methods in politics, and with those caveats also a fan of Nate's work with them. It's nice to see computational statistics get its day in the sun, even if just once in four years.

It might not be academic science, but it's still science (if it's repeatable). Whether you publish your methods for review does not influence that fact. By your definition, 90% of science done in industry wouldn't be science.

But we do have more tests than presidential elections. Silver correctly called the Tea Party wave in 2010. However, two of his Senate calls were wrong: he rated Montana as leaning Republican (Tester, the Democratic incumbent, won) and North Dakota as solidly Republican (not called yet, but Heitkamp, the Democrat defending an open seat, is up by a percentage point with all of the votes counted).

OTOH, Silver seems to assume some significant degree of correlation between different states, which is almost certainly true. One of the ways opinion polls can go wrong is incorrectly modeling the likely voter turnout (this seems to have been a particular issue for Gallup and Rasmussen this cycle). If Pollster X's LV model for Ohio underpredicts minority voter turnout, there are probably similar issues with their LV models for Florida and North Carolina. Thus Silver had larger error bars on his prediction than, for instance, Sam Wang of the Princeton Election Consortium. Even on Election Day Silver was giving Romney an 8% or so chance of winning. Wang, who seems to neglect correlation between states, got an Obama win probability approaching 100% (the probability that enough marginal Obama states were off by enough to swing the result became vanishingly small). OTOH, Wang did correctly call the Senate result.

Mu - an industry's proprietary method isn't the same as a model kept from the public by an individual.

Science done in industry generally becomes public when the resulting technology hits the market. It may well be patented, but once released it generally becomes possible to take apart a Blu-Ray laser (or whatever) and verify its means of operation for ourselves. For that reason I'm perfectly happy with the word science being used in industrial settings.

Really the repeatability is the key issue. Any scientific advance involves an explanation and a thing being explained, and their relationship is the thing to be tested. A black box is not an explanation, and can't really be tested at all except insofar as the hypothesis is "this black box does what it says on the label".

To some extent this is definitional. Surely Newton was doing some kind of science even when he refused to publish, but in general I don't think the claim to have done science should be taken seriously until the claim is generally testable.

Plenty of products on the market Are manufactured with proprietary technology. You may be able to take apart a blue-ray laser but you won't have a clue as to how the laser diode was manufactured. Many years of private scientific research goes into such things.

Ah, wouldn't it be cool if the 538 model (and your "is it better than a simpler method" point) brought topics like parsimony in modeling to the public's attention? :)

I think it's science if you just suggest he has tested a reasonable hypothesis. I think you could fairly say Silver has posited the hypothesis that pre-election polling in aggregate can reasonably predict outcomes of election. It's a simply hypothesis and his method is relatively simple, even if he keeps the exact details opaque, we know what he's doing. He's aggregating polls and using all possible combinations of electoral college combinations to predict likelihood of all possible combinations resulting in > 270 for Obama vs Mitt. There were more combinations, and more likely combinations that would result in an Obama victory such that > 90% of such possible combinations would result in an Obama victory.

His hypothesis was then tested, quite publicly, and was proven to be consistent with the data we obtained. I would say, it's a very scientific process apart from it appearing in the literature and full transparency of methods.

"Science done in industry generally becomes public when the resulting technology hits the market. It may well be patented, but once released it generally becomes possible to take apart a Blu-Ray laser (or whatever) and verify its means of operation for ourselves. "

Nate Silver's model just went through lots of tests (the elections). This is exactly the same as Matt's point about verifying the operation of the blue laser in a Blu-ray drive.

"But science has to be testable, and while and accurate prediction is a test, it doesn’t advance our understanding of the world unless we know just what it is we’re testing."

Whether any given person has seen see Silver's algorithm doesn't decide whether something is irrelevant to whether something is science. At the moment I work for a large oilfield services contractor - when my company carries out an experimental project, more people read the reports than read a PhD dissertation, or in fact most papers ever published in an academic journal (because millions of dollars are being spent). You can rest assured that just as much peer review happens in industry, academics are generally just uneducated about a lot of it because they not in industry.

Peer review certainly isn't magic, and in fact in academia the system is in many ways kind of a mess. The fact that oilfield research isn't "peer reviewed" in the academic sense is something I have no objection to whatsoever. Peer review is not synonymous with science. Conversely, if something can't be reviewed at all, then though it may be science there's no immediate reason to assume it's valid. And in fact the methods of oilfield industry are generally public - taught at every major university in fact - and are generally reviewable by any interested party. (Modulo the fact that data about specific sites is going to be kept proprietary for obvious competitive reasons.)

that's great... scientists beating each other about the purity of science while professing love for the statistics guy who is better at predicting future outcomes than anybody else...

There's some truth to this. It's easy for me to sniff about "purity" when my name's not on the line making predictions at the NYT. However, it isn't quite true that his predictions were better than anyone else, as anyone who just said "Let's assume that all the state polls are right" would have made the same predictions (with the possible exception of Florida).

1) I think Silver's activities clearly fall within the broad category of science.

As has been noted repeatedly, Silver doesn't poll, nor practice economics. Polling firms either attempt to select random samples that will allow valid statistical generalizations (clearly an example of applied science), or else, possibly, some of them attempt to select biased samples that will produce a certain result for propaganda purposes. (Silver's model attempts to correct for the latter effect, although he does not ascribe psychological motivations to the likes of Rasmussen.)

What Silver does do is aggregate polling data, and economic data that has been argued, on empirical grounds, to impact on election results, and combine them into a quantitative model that attempts to forecast election results.

It's pure hypothesis testing. The hypothesis is simply that his model forecasts the elections that he focuses on.

Intuitively, results can be measured in one of two ways. Whether his forecast is "correct" - whether his forecast comes some (necessarily arbitrary) pre-defined measure of the actual results. Or, alternately, how his forecast does relative to the many other forecasting models.

2) Silver has never claimed that his model is "scientific" any way. I think it basically is - based on objective observations, he formulates a hypothesis, and tests it. But since Silver himself isn't calling it "science", I don't see what the point is here.

I have a lot of respect for Nate Silver - he is clearly a very smart man and very good with statistics. I didn't think he would be right with his predictions and I honestly thought Obama would loose (even though I support him). The reason? Well I simply didn't believe the polls. With the long queues in the democratic areas, I thought there would be a huge loss of votes, similarly in the storm affected states - a lot of them Democratic, I thought the voter turnout would be far far less than what eventually happened. So, clearly, if the pre-election polls were accurate, Nate Silver's calculations were correct. What would be interesting to see, and I'm not sure how to do this, is how many people who would have voted, were turned off because of the 7-8 hour long queues at the polling stations. And also to look at after the storm, how many people that would have voted - simply didn't turn up because they obviously had much bigger problems to deal with (like lack of electricity, a home to live in, food etc.).

I feel much the same way about Nate Silver as I do about Obama - I don't particularly want to defend him, but he gets so many complaints that are unfair, I end up doing it.

Nate Silver did deal with vote suppression/voter turnout issues. He made a big deal of explaining exactly how his model dealt with it, and why.

I will offer a subjective but valid point here as well. One very predictable response to attempted voter suppression is backlash. If people deduce that you are trying to prevent them from exercising their right to vote, they will become very motivated to vote. And that is especially likely to be true of communities that have historically been prevented from voting, although it is also true of anyone.

What he's doing is most likely science, but without peer review, it still takes a bit of faith to assume he's going to be correct predictions in the future.

I sincerely doubt he's casting bones or throwing spaghetti noodles at a map of the US.

I think the biggest value of his progression if it holds true going forward, is debunking the sensational media around elections.. Where as the news stations skew the facts to make viewers think it's a perfect 50/50 split on votes, to keep them glued to the TV, as apposed to going... "Yeah, Candidate A is most likely going to win.....so, don't worry about it for the next 3 months."