Magnus Carlsen of Norway has won the big chess match against the defending champion Viswanathan Anand of India. This result was not surprising, though some were probably expecting Anand to put up more of a fight than he did. Only ten of the scheduled twelve games were played, with Carlsen winning three and the other seven being drawn.

This is the best thing to happen to chess in Scandinavia since Bent Larsen, “The Great Dane.” Larsen's own run for the World Championship ended abruptly when he lost six straight games to Bobby Fischer in 1971.

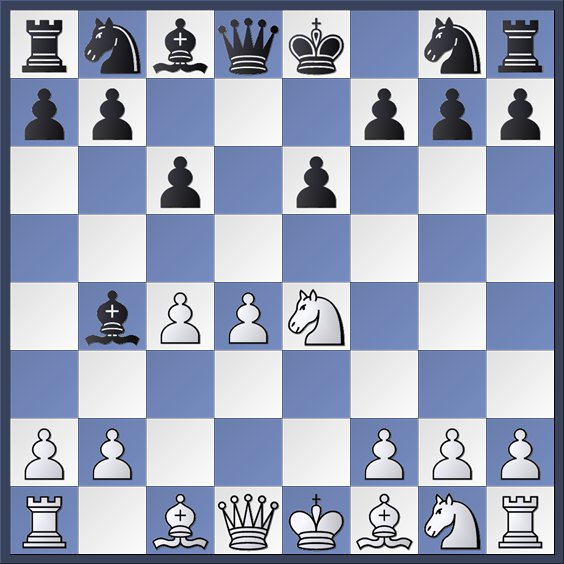

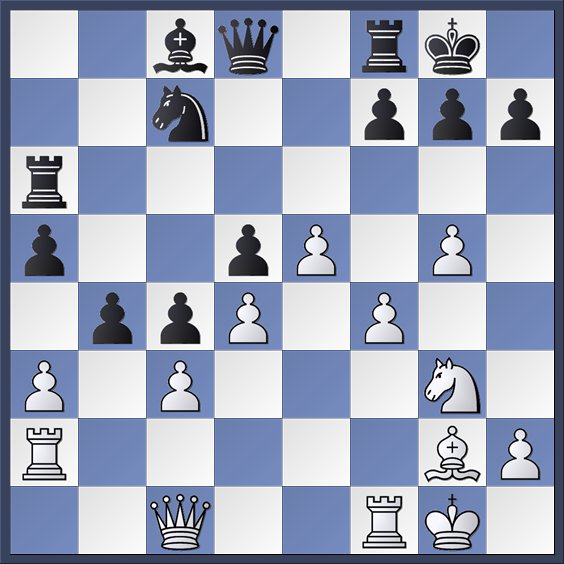

Anand's loss in Game Five is broadly representative of his problems with the match. Carlsen clearly had a strategy of playing very simple, non-aggressive, non-heavily analyzed openings, steering for quiet positions in which he had at most a small advantage. Carlsen plays such positions brilliantly. He has won many games from objectively drawn positions, just by pressing and pressing until the defense cracks. Consider this position:

We're five moves in to Game Five, with Carlsen, playing white, to move. This came out of a Semi-Slav Defense. The normal way for white to get out of the check would be to play 6. Bd2, and after black does something about his bishop we have a very standard scenario. White has more space and a lead in development, but black's position is very solid.. Instead, though, Carlsen played the mega-unambitious 6. Nc3. It's certainly not a bad move, but it does remove the knight from a strong central square, does nothing to complete white's development, and gives black a free move in reply.

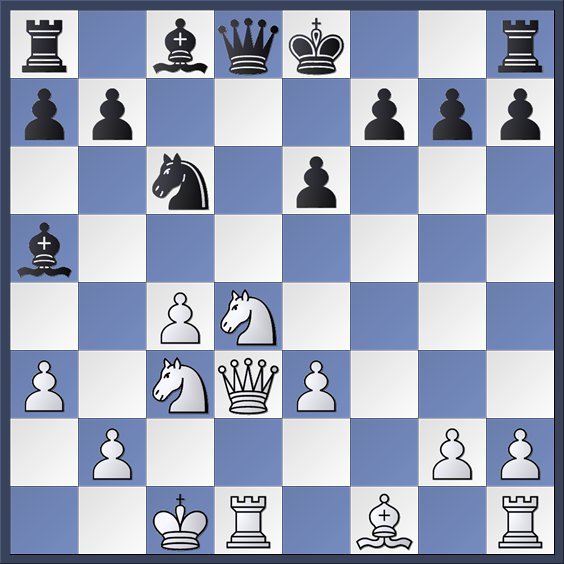

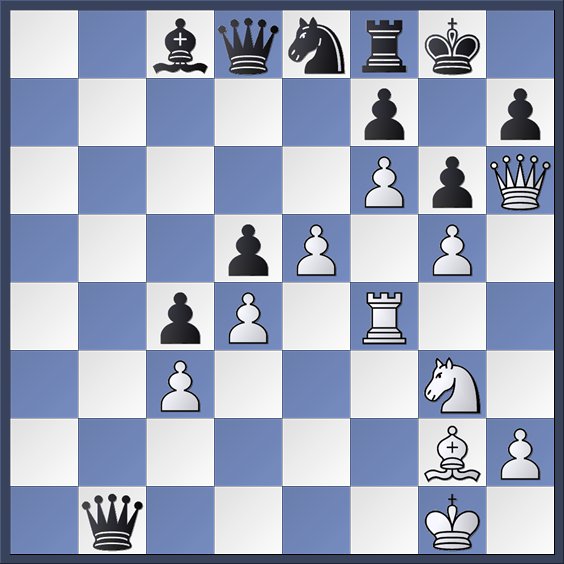

Skipping ahead a few moves, we come to a characteristic example of Anand's psychology in the match. We have a fairly standard sort of position for this opening. It is black to move. Normal moves would be to castle or to take the knight on d4, either of which improves black's position in clear ways. Instead he played the incredibly passive 13. ... Bc7. It's hard to fathom the point of this. After 14. Nxc6 bxc6 15. Qxd8+ Bxd8, Anand faces a pretty unpleasant defensive task. He has pawn weaknesses and passive pieces. White, for his part, has targets to aim at and clear avenues for activating his pieces. Objectively speaking black should be able to hold. But that is small comfort when you have to face one strong move after another from Carlsen.

Anand defended well for a while, but finally made the inevitable error.

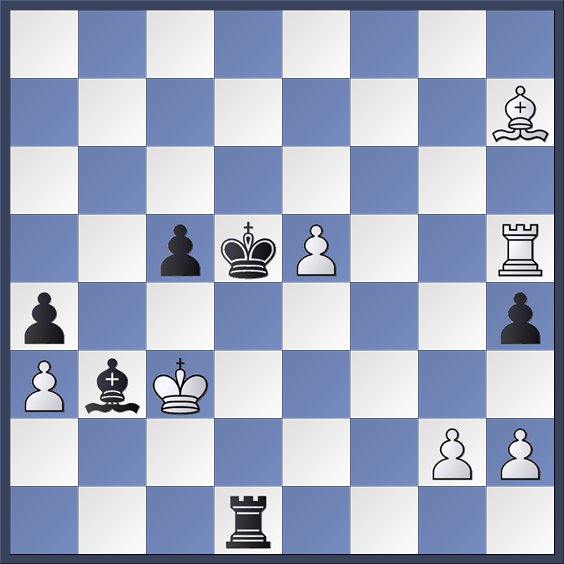

A few moves ago, black sacked a pawn for some activity. This was not an error by itself, but it was perhaps doing it the hard way. But now black has an easy draw with 45. ... Ra1, going after the a-pawn. A cute point is that after 46. Bg8+ Kc6 47. Bxb3, black has the important zwischenzug 47. ... Rxa3! He will pick up the bishop on the next move, and his passed pawns on the queenside will provide enough counterplay to hold the draw. Instead Anand played the incomprehensible 45. ... Rc1+, and quickly went down to defeat.

Anand then lost Game Six in similar fashion. A lackluster opening led to a small but nagging advantage for Carlsen. Anand defended well for a while, but then blundered after relentless pressure from Carlsen. This left him down by two points, which is all but insurmountable in a short match.

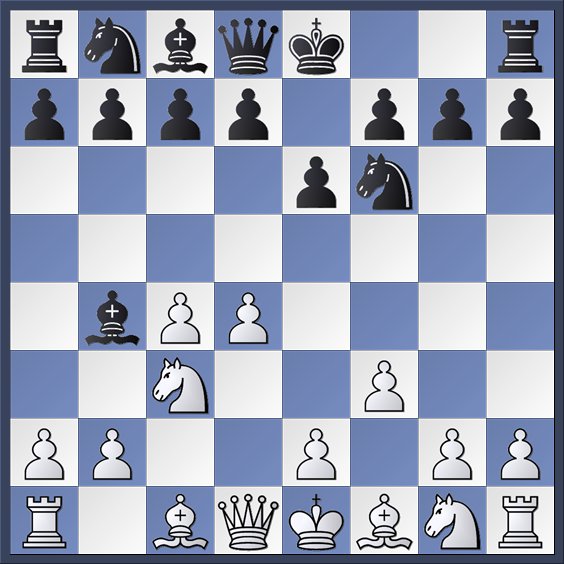

To his credit, Anand really went all out as white in Game Nine. This was effectively his last chance to get back into the match. We pick up the action after white's fourth move:

Rather than bang his head against Carlsen's Berlin Wall again, Anand switched to a queen-pawn opening. Carlsen replied with the Nimzo-Indian Defense, which is a very popular choice among top players. In the Nimzo, black takes a cagey approach to the opening. Rather than occupy the center with pawns and pieces, as classical principles recommend, black declines to occupy the center at all. Instead he tries to influence it from afar. White has a variety of approaches, and Anand's choice of the Saemisch Variation with 4. f3 is one of the most aggressive. White says, “You decline to occupy the center? Fine by me! I'll take all the space you give me, thank you very much.” White is going to follow up with moves like e4 and g4, setting up a big center and preparing a king-side pawn storm. The downside is that white's pawn move robs his knight of its best square, and does nothing to improve his development.

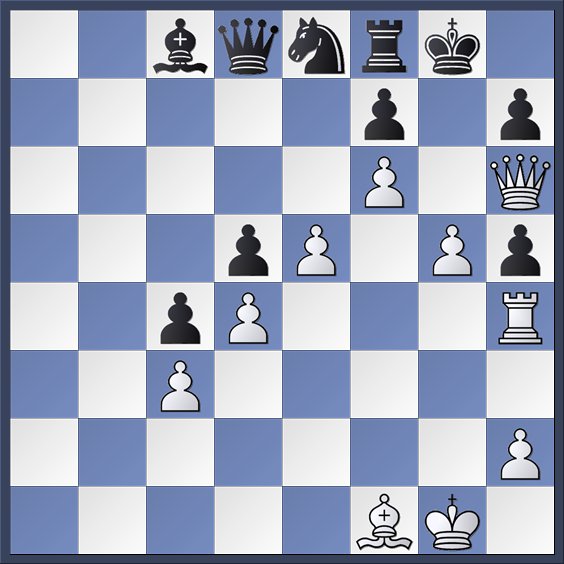

We skip now to one of the crucial moments of the game. We see below that White has dutifully implemented his plan, and black, to put it simply, is all but busted on the king-side. White's pawn storm is pretty menacing, and black has no good way of shutting it down. White has such a space advantage over there that, if he is given enough time, he will simply push black clean off the board. Carlsen is in trouble, and I've noticed some commentators claiming that Anand was winning somewhere around here.

So Carlsen sought counterplay on the queenside, bringing us to this position with Anand to move:

Play continued: 20. axb4 axb4 21. Rxa6 Nxa6. This received considerable criticism, most notably from Hikaru Nakamura who felt the exchanges were not in keeping with the spirit of the position. When you are attacking you generally want to keep pieces on the board. Nakamura suggested either 20. a4, which tries to shut black down on the queenside before getting back to the fun on the other side of the board, or 20. f5, which just scoffs at black's queenside pretensions and gets on with the king-side festivities. Interestingly, though, the computer agrees with Anand's play, at least after about a minute of analysis.

At any rate, Anand's play might not have been the most incisive, but after 22. f5 b3 23. Qf4, white's attack is formidable. Black is hanging by a thread. But a thread is all Carlsen needs!

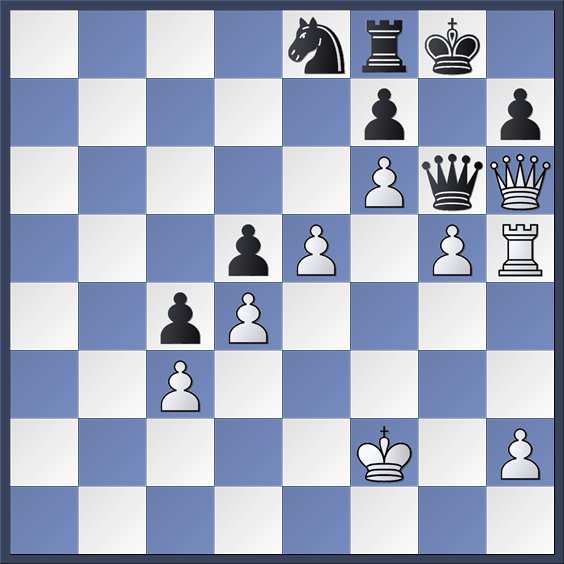

A few moves later we come to the crucial position:

The first thing we notice is that black has two queens. The second thing we notice is that white has the very strong threat of Rh4 followed by mate on h7. The third thing, though, is that white is in check, and that is what keeps black alive.

The nice thing about having an extra queen is that you can be pretty cavalier about sacrificing it. Normal play would now be 28. Bf1 Qd1 29. Rh4 Qh5! 30. Nxh5 gxh5, bringing about this position:

If white now plays the obvious 31. Rxh5 (or 31. Qxh5 with the same idea), black just plays 31. ... Bf5, which shuts down the attack. White should still be able to hold a draw, but he is certainly not winning. And if white tries 31. Bh3, to eliminate black's strong defensive bishop, black can still get a diagonal-mover to the key diagonal with 31. ... Bxh3 32. Rxh3 Qb6! 33. Rxh5 Qb1+ 34. Kf2 Qg6:

and black is just winning. A pretty piece of chessboard geometry!

The actual conclusion of the game was anti-climactic. Anand just blundered with 28. Nf1, which opens up the diagonal from e1 to h4. Black just wins on the spot with 28. ... Qe1. It's the same defensive idea as before, except that black will win a rook when he sacrifices his queen on h4.

Even though Anand lost this game, it does make clear what Anand needed to do to be competitive in the match. Passively defending against Carlsen is not a good plan. Anand passed up several opportunities to complicate positions early in the match.

So, congratulations to Magnus Carlsen! I think all chess fans regard him as a worthy champion. He is strong enough and young enough to dominate for a long time, so long as he maintains his interest in chess. As for Anand, no tears for him. He has been a major force in world chess going back to the late eighties. He will deservedly be listed right alongside the great ones in chess history.

Maybe he will now follow Kasparov's example: Retire from chess and get involved in politics!

While I admire Carlsen I can't feel enthusiasm.

Jason,

would you say that your interest in the World Championship is more in the excitement of the competition or the interest in seeing good games?

By the way,

surely Carlsen's achievements are the best thing to happen to Scandinavian chess ever?

Jr--

It's a little of both. World Championship matches often don't produce great masterpieces of the chess boards. It's not uncommon even for the great ones to produce subpar chess, given the strain of the competition. But there's such a long tradition behind the world chess championship that the event itself is always something remarkable, even if the games themselves are sometimes disappointing.

And, yeah, I think you can say that Carlsen's achievements are a big deal for Scandinavian chess. As I mentioned at the start of the post, Bent Larsen is the only other Scandinavian player I can think of who played at the highest level. There has always been a contingent of very strong players from that region, but not at the world championship level. Perhaps I've forgotten someone. It will be interesting to see if there is now a boom in Norwegian chess, just as there was a boom in American chess after Bobby Fischer won the title.

Carlsen is a big national hero in Norway at least, and the games were televised with large viewing audiences. The long term effect remains to be seen of course.

Thanks for the match wrap-up, Jason. Seemed to me Anand was playing rather like "a pitcher who's lost the hop on his high hard one." (Is that from Raymond Chandler? Can't quite recall where I picked that one up.)

Carlsen certainly has a way of winning from positions that look like there's just nothing there. Gonna be tough for anyone to dethrone him. But somewhere there's a kid with a chessboard....