tags: London England, London Zoo, sciblog, zoological gardens, travel

After a leisurely morning walk through part of London's Regents Park, Bob O'Hara and I then spent the rest of the day at the London Zoo.

The London Zoo is quite proud of their environmentally-friendly facilities, and they have a sign near the main entrance that describes their water conservation project;

Sign near zoo entrance describing the zoo's water conservation project.

London Zoo.

Image: GrrlScientist, 2 September 2008 [larger view].

The London Zoo has been in existence for nearly 200 years. It has been at the forefront of many innovations for keeping wild animals in captivity, most notably, the world's first international co-operative breeding loan (for Arabian Oryx, a species that has been successfully reintroduced back into the wild).

Currently, London Zoo is undergoing renovation so animals will be kept in enclosures that more closely resemble their natural habitats. I was lucky enough to see many of these new enclosures, particularly the renovated aviaries, such as the Blackburn Pavilion, which houses tropical rainforest birds and which had been reopened to the public only a few months before I visited.

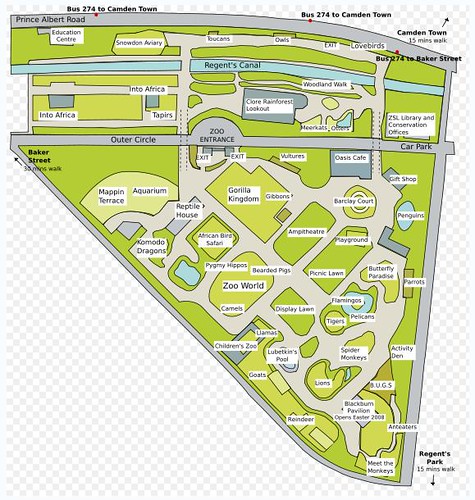

Here is a map of London Zoo for you to refer to;

Because I wanted to photograph the location where the first Harry Potter movie had been filmed, we started our zoo adventure in the zoo's Reptile House. After I photographed the exhibit where Harry Potter learned he could talk to snakes after he freed a Boa Constrictor (Note: a Black Mamba occupies the actual exhibit), Bob and I went exploring, cameras in-hand.

I am especially fond of frogs, particularly the astonishingly colorful poison dart frogs from Central and South America. These are small, fast-moving, diurnal frogs that are brightly-colored as a warning to potential predators that they are poisonous, and therefore, inedible. The London Zoo frog enclosure housed several species, but alas, these frogs were nearly impossible to photograph because they moved so quickly that they ended up as colorful streaks or blurs, and also because the glass reflection ruined nearly all of the other photographs that weren't blurs.

Below is one image that actually isn't too bad, but I did not write down the scientific name of this species, so someone will have to provide that for me (Golden Poison Dart Frog, Phyllobates terribilis?);

Golden Poison Dart Frog, Phyllobates terribilis?

London Zoo.

Image: GrrlScientist, 2 September 2008 [larger view].

Near the poison dart frog exhibit in the Reptile House were several Egyptian Tortoises, Testudo kleinmanni. I was absolutely enchanted by this particular tortoise (below) because it was calmly munching away on leaves near the front glass panel, making itself a convenient photographic target .. erm, subject. There were several other individuals in the same enclosure, one of which was running so fast that all my photographs of it were blurred!

Egyptian Tortoise, Testudo kleinmanni.

London Zoo.

Image: GrrlScientist, 2 September 2008 [larger view].

Egyptian Tortoises are really amazing animals. They are a severely range-limited species, being found only in a narrow band of coastal desert that stretches from Libya to Israel along the south-eastern Mediterranean Basin. They have a very small body size (only 10-15 centimeters long) for a tortoise, which allows them to both heat up and cool off quickly, and their pale gold coloring further prevents them from becoming overheated. They are herbivores, as you can see in the above image, and they spend the hottest parts of the day (and of the year) hiding from the sun under bushes or in rodent burrows.

Sadly, these small animals are one of the most endangered tortoises on the planet due to the combined effects of -- what else? -- habitat destruction and the incessant demands of the illegal pet trade. It is estimated that the Egyptian tortoise will become extinct in the wild if nothing is done to correct these issues.

Near the Reptile House exit, I happened upon a familiar face: Gila Monsters;

Reticulate Gila Monsters, Heloderma suspectum suspectum.

Image: GrrlScientist, 2 September 2008 [larger view].

These large, slow-moving and venomous lizards are native to the desert southwest of the United States. Even though this animal is venomous, it moves so slowly that it poses no threat to humans, but that doesn't stop stupid people from killing them whenever and where ever they run across them. This indefensible propensity to kill everything in our pathway is simply outrageous.

"I have never been called to attend a case of Gila monster bite, and I don't want to be. I think a man who is fool enough to get bitten by a Gila monster ought to die," wrote Dr. Ward in the September 23, 1899, Arizona Graphic. "The creature is so sluggish and slow of movement that the victim of its bite is compelled to help largely in order to get bitten."

This lizard eats irregularly -- it is estimated that it eats only between five and ten times per year in the wild -- but it is a glutton when it finally does manage to land a meal. In fact, this large but unobtrusive lizard mostly lives underground, coming out in the early mornings to sniff out and eat the eggs of birds and reptiles, although it will also add the parents to its menu, if it can catch them. Not much escapes the Gila Monster's keen sense of smell: it is rumored to be able to follow the trail of an egg that has been rolled across the sand.

Another interesting anatomical feature of the Gila Monster is its tail: it is filled with fat. Indeed, this animal stores extra fat in its tail so it can survive long periods between meals. This fat storage ability apparently affects its tail in other ways as well: if the Gila Monster's tail is broken off, it cannot regenerate -- quite unusual among lizards.

After leaving the reptile house, Bob and I got down to business: he wanted to see the Komodo Dragons, and I wanted to see all the aviaries on the zoo grounds. Since there are fewer Komodo Dragons, and they are clumped together into one place on the zoo grounds, we decided to find them first.

For reasons that I cannot recall, we did not see the Komodo Dragons .. were they off exhibit? Were they being punished for eating an unsuspecting visitor? Bob, you'll have to remind me why we did not get to see them.

Anyway, as a tribute the invisible Komodo Dragons, I took a picture of this building (above) which was supposed to be on the way to the dragons, although how near it was to them, I don't know since we never got to see them.

Disappointed, Bob and I then wandered off in search of all the aviaries, and there are plenty of those to experience at London Zoo! Along the way, we saw several diminutive cattle from the Indonesian island of Sumatra. These tiny animals are known as Lowland Anoa, Bubalus depressicornis;

Lowland Anoa, Bubalus depressicornis, from the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.

Image: GrrlScientist, 2 September 2008 [larger view].

Along with its closest relative, the Mountain Anoa, Bubalus quarlesi, the Lowland Anoa is one of two species of water buffalo that are native to Indonesia. The Lowland Anoa are the smallest species of wild cattle, being roughly as tall at their back as a Shetland pony. Both Anoa species live deep in undisturbed rainforests, although at different elevations, as their common names imply. Unlike most mammal species, which live in herds, Anoa live singly or in pairs, although they tend to form larger groups when the females are ready to give birth.

Both Anoa species are endangered due to poaching for their meat and hides, and for their horns, which are used in traditional medicine. Human encroachment into their formerly unspoilt rainforests is adding more pressure to their dwindling populations by destroying their habitat. It is unlikely that the total population for either species exceeds 5000 individuals.

After photographing the Anoa, I was inspired to seek out and photograph the zoo's Okapi, Okapia johnstoni. Okapi were my among most favorite animals when I was a kid, and I still have a soft place in my heart for them today. Along the way, Bob and I ran across their closest relatives, Giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis. This particular individual was very adept licking her nose with her tongue: a talent that neally all three-year-old human children aspire to;

I was surprised to see that the London Zoo erroneously classifies all Giraffe into one species, even though we all know that they were recently reclassified into at least six distinct species based on DNA data. Anyway, I am no expert at recognizing species of Giraffe based on their markings, so I have no clue as to which species the zoo's Giraffes belong to. But I hope that London Zoo does some DNA work on their animals to make sure they are not inadvertently hybridizing them.

Bob and I found the Okapi enclosure, but because there were workmen present, making extraordinary amounts of noise and generally being annoying, the Okapi had wisely hidden themselves out of sight. One of the workmen said I might get lucky and see one if I waited long enough, but after waiting for roughly 20 minutes without even a glimpse of the elusive Okapi, I decided it wasn't worth waiting any longer since the birds were also calling out to me!

But nevertheless, I was mightily disappointed that I did not see Okapi after traveling roughly five thousand miles! So here's a picture of an Okapi for both you and me to admire, courtesy of the Denver Zoo;

The elusive and peculiar Okapi, Okapia johnstoni,

a relative of the giraffe that dwells in the dense rainforests

of the African Congo.

Image: Denver Zoo.

While reading the background story of the London Zoo, I learned that it was once home to another of my childhood favorite animals, so I am going to use Okapi as a very weird sort of lead-in to discuss that particular species.

I suppose that some of you might have noticed that Okapi markings are nearly the reverse of the enigmatic (and now extinct) Quagga. But did you know that, because of their markings, Okapi were actually once thought to be a member of the horse family instead of being related to Giraffes?

Here is a picture of the London Zoo's lonely, and now forever dead, Quagga, to remind you of what they looked like;

The extinct Quagga, Equus quagga quagga --

the only photograph ever taken of a living individual.

London Zoo.

Image: Wikipedia [larger view].

The extinct Quagga, Equus quagga quagga, is now known to be a subspecies of the Plains (Burchell's) Zebra, Equus quagga burchelli, according to DNA data published by the Smithsonian. Before Europeans began to roam the planet, shooting, eating or otherwise destroying everything in their paths, Quagga were once found in great numbers throughout regions of South Africa. The Quagga's strange name is onomatopoeic, since it was said to resemble their call.

While wandering from one aviary to another, the zoo surprised me by having more than just animals to keep people amazed: it also had a carousel and a fair amount of artwork distributed throughout the grounds.

At the time, I photographed this carousel without thinking about it much (I do love carousels), but now I wonder if there was a Quagga on the carousel? Does anyone know if a Quagga (or even if a Zebra) has ever been included as a carousel ride? I mean, there's a seahorse ride on the zoo carousel, so why not a Quagga?

Clock sculpture with Toco toucans.

London Zoo.

Image: GrrlScientist, 2 September 2008 [larger view].

This strange clock with Toco Toucans [read more about it -- includes several streaming videos of the clock in action] on each side was located outside of one of the aviaries, which also featured a number of museum-like exhibits detailing the many special features of birds: their feathers; bone structure; eggs; and whatnot.

I really liked this bird sculpture (above), located near the Snowdon Aviary, that looked like an avian embryo in an egg. The style is evocative of artwork created by several of the Native American tribes of the Pacific Northwest.

And then there's the driftwood horse art .. need I mention that another of my childhood favorite animals are horses?

Above is a larger-than-life driftwood sculpture of an Arabian horse by British artist, Heather Jansch. I've seen photographs of her work before, including this particular piece, but this was the first time I'd ever seen her work in real life. It was absolutely striking. I really enjoyed seeing this particular piece, and I took this opportunity to snap a lot of photographs.

Below is a really wonderful video detailing some of Heather's work and the process of finding and assembling these pieces into a finished piece, including the London Zoo horse sculpture (music: "A horse with no name" by America [3:50]);

Tomorrow, I will show you some of the images of birds I took at the London Zoo. Some of these bird images will probably show up as my daily mystery birds at some point in the future, too (hint, hint).

I think the Komodo Dragons were hiding - I've just checked and I've got a couple of really crappy photos of them. Incidentally, my interest stems from reading David Attenborough's Zoo Quest books as a kid. I wonder if my copies are in Helsinki, or stuck in a basement in the north of England.

I'll be surprised if you only write one post on the birds - as I recall, you did take a few photos...

I have a photo of a London Zoo golden poison dart frog (Phyllobates terribilis) here. It looks like it might be the same species as your yellow poison dart frog.

bob -- i remember now. i guess the disappointment was so traumatic that i blocked that memory out until you reminded me of it. (haha).

tristram -- thanks for the species ID. i was wondering if it might be a golden poison dart frog, but was unable to find any reasonable images on the internet that would give me enough clues to comfortably ID it as such .. anyway, we'll see if anyone steps up to correct my ID now that i've committed myself by adding it to the photoessay.

London Zoo is one of my favourite places in London, but despite living in London myself, I rarely get to visit it.

There is some more information on the new clock at the website of the inventor:

http://www.timhunkin.com/a136_zoo-clock.htm

I've never been to England, or the London Zoo, but I remember as a kid reading a book called "To the Zoo in a Plastic Box", about these two guys whose job it was to travel around the world collecting interesting insects for the London Zoo's insect house. I though that was really cool. So when I saw that you were doing a piece on the London Zoo, I hoped for photos of the insect house.

Guess I'll have to go there in person for that.

Very impressive reptile house photos grrl - how do you get nice exposures in there without horrible flash bounceback off the glass?

DTL -- thanks so much for that wonderful website link about the zoo clock!

john -- i wish i had the time to visit (and photograph) the insect house, too! but unfortunately, there was more to see and photograph than there was hours in the day, so i focused on the birds, mostly, for that reason. but if i had the chance to visit the london zoo again (and i sincerely hope i do), the insect house is a priority.

tai -- i rarely use flash in my photography because it destroys color. when i use flash, i specifically mention that i have done so because i think it alters the image quality so much.

I actually used to work at London Zoo on what was then the 'Cotton Terraces' (now the Into Africa scetion) with the giraffe, okapi, tapir, indian rhino, zebra and the famous Arabian oryx. Great times and I thoroughly enjoyed myself. As to the giraffes species, we knew for many years that we had hybrids in stock but there was little that could be doen about it given the lifespan of the animals. However, as they began to age (and sadly die, only one of the animals I worked with is still there) purebreads were brought in and the older females were prevented from breeding, so now the whole group is from a single subspecies (probnably now species, though I forget which!).

As for the signs they will tkae a while to get up to speed since these things take time and money to get done. However, I should add that inevitably not eveyone agrees that all of these groups should be given the full rank of species (and it's a bit unfair to expect a zoo to jump to everyone's classification) and secodnly that work was actually funded by the Zoological Society of London in the first place, so give them soem credit.