By way of Digby, we come across this proposal of how to reach 95% percent renewable energy by 2050. Before I get to some of the issue I have with the study (which is actually pretty good), I want to lay out my general views on energy use.

First, I'm not a 'fan' of nuclear power. While thorium-powered reactors would be a vast improvement over traditional reactors (and newer designs regardless of energy source would fail much more safely compared to older ones), even thorium isn't perfect. But what's really stupid are all of the calls for immediately stopping the use of nuclear power. (And, please, the 'well just shut down this one--which happens to be near me' argument doesn't work; every reactor is near somebody, including the Mad Biologist). Currently, the U.S. generates twenty percent of its electrical needs with nuclear power (pdf). If we take those reactors offline, we have to increase the amount of electricity generated using CO2-emitting sources by 25 percent. And for those who argue renewable energy will fill the gap, it won't happen overnight--and meanwhile we're increasing carbon dioxide emissions. From a public health perspective, worldwide, fine particle pollution kills over one million people per year, and thirty percent of that pollution comes from electrical power generation. We'll only make that problem worse too.

Since most of our 'renewable' energy currently comes from hydroelectric power--damming rivers--we will have to massively increase our solar, wind and tidal generation capacity. Even if we regain that lost twenty percent capacity, we still haven't taken a single coal-burning plant offline. If anything, we should shut down nuclear power last. I don't like this situation, but I think it's the least worst option.

Having said that, I don't see any other alternative, but to move towards renewable energy. Even if we can only get to fifty or sixty percent renewable energy, that's a marked improvement, and one we desperately need.

Ok, onto the World Wildlife Federation Study (pdf).

Overall, it seems technologically feasible, for the most part. There don't seem to be many 'magic asterisks.' The only magic asterisk is algal biofuel production. That is just supposed to magical account for ~5% of power production, even though we really have no idea if it will work (and in the technical part of the report, the authors admit as much). But still 90-95% renewable energy still seems pretty good. As with all estimates, the report is based on future assumptions, but, from a technical standpoint, nothing leapt out at me as ludicrous, or simply not adding up (and, of course, the assumptions could be wrong in our favor too).

The real problems appear to be political in nature. First, a minor point. The report is called a path to 100% renewable energy. It's not: by 2050, according to the report itself, 95% of energy production could be renewable. While that sounds like nitpicking, anyone involved in the intersection of science and public policy knows that opponents of these proposals will jump all over that difference in an attempt to cast doubt. The report does itself no favors by overstating the proposals (that said, 95% would still be amazing).

But the major problem with the report is how green housing is portrayed (e.g., p. 220). First, the current rate of retrofitting existing housing would have to increase three to six-fold. Not impossible, but much more than we're doing now. The report also assumes that, as a result of retrofitting, heat consumption will drop eighty percent and the rest will be made up with solar or geothermal power. Kinda iffy, considering most current greening initiatives don't come close to eighty percent. And, as the report notes, there is a principal agent problem:

The principal agent problem, or 'landlord-tenant-problem' refers to the situation where the principal decision-maker for an investment is not the person which would benefit from the investment. This can lead to barriers to cost-effective investments being made. A classic example are energy-efficiency measures in buildings which are not owned by their occupiers: the investment has to be made by the owner, but the reduced energy bills are beneficial to the tenant.

But the most difficult problem--and one I dealt with here--is the policy objective of reducing energy use in transportation, with the following examples (p. 221; italics mine):

⢠Policies delivering high-quality public transport at competitive prices

⢠Dis-incentivising car use and incentivising other modes, e.g. congestion charging, public cycle hire schemes

⢠Sustainable urban / land-use planning to sustain local and / or low-energy transport systems

⢠High speed railway systems between large city centres to challenge short- and medium distance air travel

Let's just pretend there aren't Republican governors who give away free money for SUPERTRAINS (although some kinda fast trains would be more useful). It's the "sustainable urban/ land-use planning" that's difficult. As I put it:

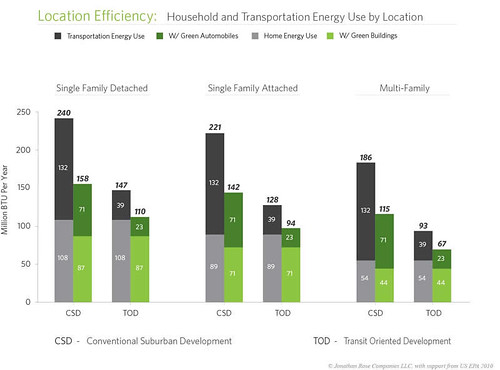

One of the best ways to reduce the amount of stuff we have to light on fire is to move from single detached housing in areas with no efficient mass transit to apartments with access to mass transit (keep in mind that residential use and transporation account for about two-thirds of total energy consumption). In other words, we have to massively 'desuburbanize' and simultaneously 'reurbanize.'

Just how likely is that? Hell, whenever I write something nice about Boston, I get people showing up and claiming that they couldn't live in the city because those people will rape all their stuff and steal all the women (or is it the other way around? I get confused).

I then listed a bunch of relatively modest things we can do--and I don't think they're very likely to happen. Because this is the U.S. reality:

My impression reading a lot of commentary about renewable energy is that there's this fantasy that we just have to build a bunch of windmills, install some solar panels, buy a Prius, and replace our windows and all will be well. But the brutal reality is that we need to urbanize our suburbs. We need to discourage detached housing. We need to massively fund local mass transit--not just SUPERTRAINS. We can't have people firing up their own personal combustion engine to buy groceries. Most people will not be regularly driving to and from their detached house with a big front lawn and large backyard. This will require the kind of effort only seen with war mobilization--and, these days, we don't even really mobilize most people even as we fight two wars (or three, if we count Libya).

I understand why the report downplays this: across the board, developing countries are actually increasing suburban housing, and de-urbanizing. In the U.S., even though cities are finally gaining population, this simply means that the increase in suburbanization is slowing. (Hooray for the first derivative!) Urbanization policies would be immensely unpopular, and meet widespread resistance (although some suburbanites would support urbanization if they could afford it).

Politically, I'm not sure how we fix that, but we need a strong dose of realism here: until we confront how deurbanization has contributed to our rampant energy needs, we won't substantially tackle the global warming problem.

Ah, but we can do 100% by 2050. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/01/110126091443.htm

As the authors of this study state, it's more a problem of intent than ability. If economics were using long-term and cost-internalized standards, as they should, I have no little doubt the renewables would be far cheaper than coal, gas, oil, and nukes. Even if we just took their subsidies and used it to build renewable generation and infrastructure, the fossil and nuke economies would start to crumble. And that, I think, is the single reason that this hasn't happened.

More pipe dreams of those who don't like suburbs. In a book on the electrification of the US, it talks about how the invention of the electric streetcar resulted in cities getting larger in area as the middle class could move out into surrounding land. The same theme occurs in City of the Century, a story of Chicago. There the railroads did some of the work as well. In both cases the desire for single family homes predates the introduction of the auto. Actually for its time we had quite a good high speed rail network in 1910 in the Northeast and Indiana, Ohio, Illinois and Southern Mi, called the interurbans. But they did not survive the convenience of the car.

So the desire for the house and lot predates the auto the auto just enabled more to realize the dream. But of course the dictators of the wise don't want to realize history because it does not fit their view of the world.

Part of the objection to apartments is simply the lack of personal freedom and uncertainty. I can't improve my insulation, I can't install solar power, I can't paint the outside, I can't buy new/improved appliances, I can't change the wiring to suit my needs, I can't knock down obstructing walls or remodel. More importantly, I can't be sure I won't have to move any given year, which means I can't do things like put in permanent gardens, greenhouses, etc. because I'd have to leave them behind. Even if I own a condo, I still don't have 100% freedom with the yard etc. because of other tenants.

As I pointed out before, Providence shows that you can have single-family homes with yards etc. within the city and conveniently close to bus lines, eliminating most of the issues with suburbs but allowing you to own a home.

Given how it's obviously hard to sell people on "apartments for all!", maybe focus on easier plans that have similar impact, like expanded bus lines, more frequent buses, and tax incentives for both homeowners and landlords to green up the homes.

Honestly, your apartment-advocacy seems like me and advocating childfree living on environmental grounds - while our respective choices clearly have positive environmental effects, they're also counter to the strongly-held desires (rational or not) of so much of the populace that they're unlikely to ever become a major component of the move towards lower impact (or won't until long after other factors have dealt with the problem).