"Let the great world spin for ever down the ringing grooves of change." -Alfred Lord Tennyson

Welcome back, for another Messier Monday here on Starts With A Bang! Each Monday, we've been taking a look at one of the 110 Deep-Sky Objects that make up the Messier catalogue, a mix of clusters, nebulae, galaxies and more, all visible from most locations on Earth with even the most basic of astronomical equipment.

When you think of our local group of galaxies, you probably think of the Milky Way and Andromeda, and then "everything else" as an afterthought. I can hardly blame you for that; at only 2.5 million light years, it's the biggest, brightest extended object in the night sky. With an estimated one trillion stars, it's the biggest galaxy in our neighborhood, followed by the Milky Way at number 2.

But did you ever wonder what the third largest galaxy in our neighborhood is?

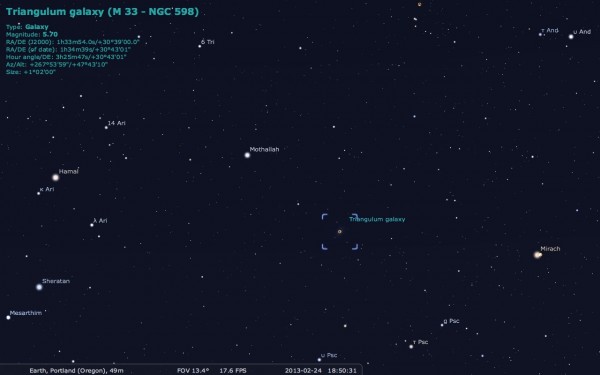

Believe it or not, there's another galaxy within our local group that's actually (barely) visible to the naked eye: the Triangulum Galaxy, also known as Messier 33. Here's how to find it, but only on nights where there's low light pollution. (I.e., not tonight, when there's a full moon!)

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, from http://stellarium.org/.

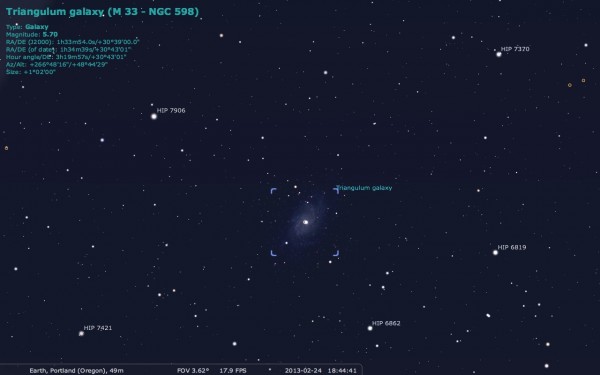

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, from http://stellarium.org/.

Early in the night, the bright clusters Hyades (highlighted by Aldebaran) and Pleiades are prominent, with Jupiter presently between the two. If you draw an imaginary line connecting Aldebaran to the Pleiades and continue, it will take you across the sky towards the bright star Mirach (in the constellation of Andromeda), not so far away from the bright "pair" Hamal and Sheratan (in Aries).

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, from http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, from http://stellarium.org/.

But the small constellation Triangulum is found in there, and practically midway between the Hamal/Sheratan pair and Mirach is a very faint object just barely visible to the naked eye. It's the only Messier object in this constellation, and whether you can see it or not is a great test of how dark your skies are.

In skies darker than the suburban/rural transition (a "4" or lower on the Bortle scale), you've got a great shot at finding it! Through a good pair of astronomy binoculars, a small "ring" of five stars appears to encircle this deep-sky object, and -- although it will be mind-numbingly faint -- you'll never forget it if it appears for you.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, from http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, from http://stellarium.org/.

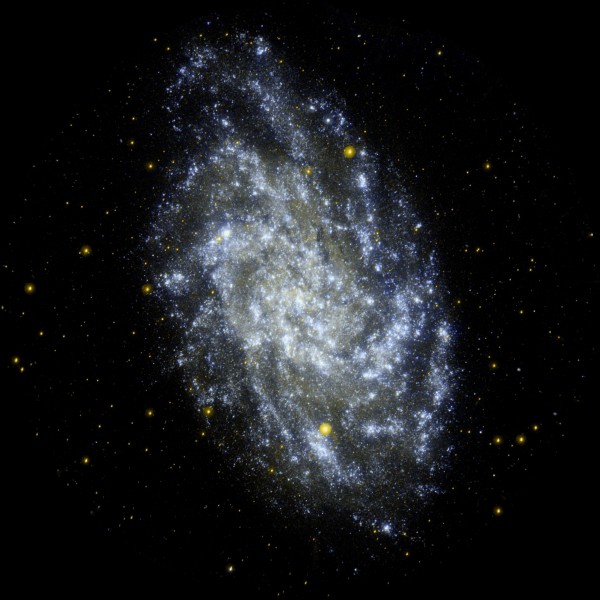

Why's that? This is a real "small wonder" of a galaxy. With just 40 billion stars, it's only 10% as massive as our Milky Way, but appears as the second-brightest galaxy in the sky because it's so close! At just 2.8 million light-years distant and inclined at 54° to our line-of-sight, it gives us the best "face-on" view of any close galaxy!

Image credit: Astrophotography by Alson Wong, http://www.alsonwongastro.com/.

Image credit: Astrophotography by Alson Wong, http://www.alsonwongastro.com/.

The only drawback is that it's so close that low-magnification viewing is practically a necessity! But if you build up your observations over long enough time periods, you can develop a clear, spectacular view of our next-door neighbor!

Image credit: Robert Gendler of http://www.robgendlerastropics.com/.

Image credit: Robert Gendler of http://www.robgendlerastropics.com/.

Because it's so close, we've not only seen some spectacular views of M33, we've also learned a ridiculous amount about astronomy from it. There are the red areas, which are indicative of star-forming, ionized regions of space, sweeping spiral arms, along with billions and billions of stars.

The many variable stars in this galaxy are well-studied enough that our figure of 2.8 million light-years is pretty robust for its distance.

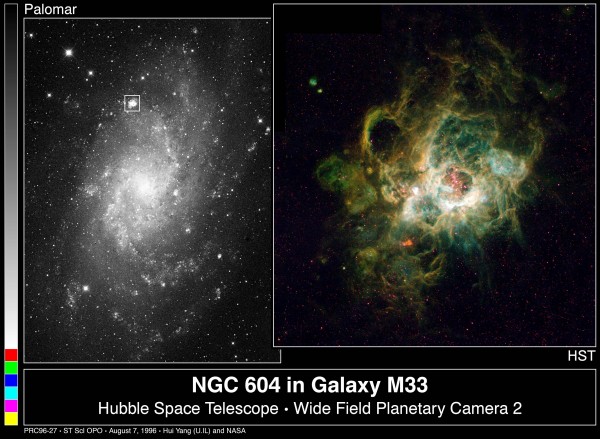

You may also notice that one of the reddish regions is absolutely huge! This region is known as NGC 604, and it is the largest, brightest star-forming region in the entire local group!

It's over 40 times as large and 6000 times as bright as the Orion Nebula, with about 200 prime candidates for a spectacular Type II supernova! If this star-forming region were located in our neighborhood of the Milky Way, it would outshine every star and planet in the night sky.

But -- as is often the case -- there's a ton to be learned from looking in a multitude of wavelengths.

From the visible light images, we learn that there's practically no bar in the center of this galaxy, and from the motions of individual stars, we also learn that there's no supermassive black hole in there, either. In fact, if there is a massive black hole, it's less than three thousand 1,500 solar masses, whereas supermassive black holes normally range from a few million to many billions of solar masses.

But there are some amazing things happening.

The Spitzer Space Telescope shows us this galaxy in the infrared, and highlights extended dust far past where the spiral arms are. Reconstruction of faint IR signatures shows that there was once a gravitational encounter between M33 and the great Andromeda galaxy, and we now think that ourselves, Andromeda and the Triangulum galaxy will all eventually merge together, with the most probable outcome being a merger of Andromeda and the Triangulum galaxy maybe a billion or two years before the Milky Way-Andromeda merger we're all looking forward to.

This Ultraviolet view, from GALEX, shows the location of bright, young blue stars, which the Triangulum Galaxy is full of! The spiral arms are clearly traced out in the Ultraviolet, but the central "bulge" that we're so familiar with in our own galaxy seems absent.

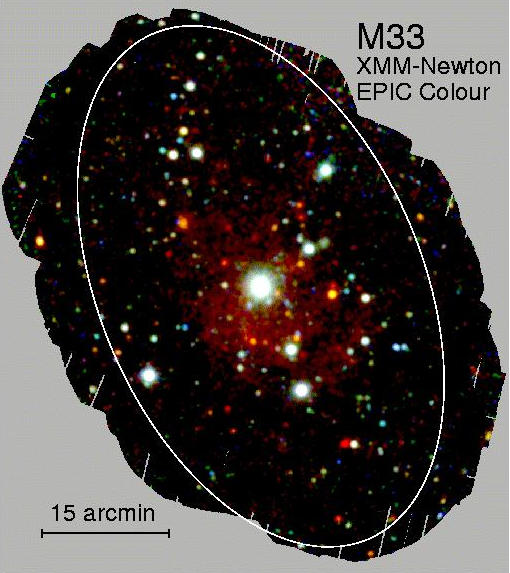

In fact, there is no central bulge in this galaxy, but something fishy is happening in there. And that's something we only know thanks to our X-ray eyes.

There's an ultra-luminous X-ray source coming from the center of the Triangulum galaxy, which is the most luminous X-ray source in the entire local group! This sort of X-ray source very close to the center of a galaxy is thought to be extremely rare, and yet, out of the three major galaxies in our local group, there it is.

Unlikely events happen all the time in the Universe, and we have the chance to enjoy one right here in our own backyard.

Image credit: © Oriol Lehmkuhl and Ivette Rodríguez of http://astrosurf.com/.

Image credit: © Oriol Lehmkuhl and Ivette Rodríguez of http://astrosurf.com/.

So look for the Triangulum Galaxy, Messier 33, the next time the skies allow it, and now you know what you'll be seeing!

Including today, we’ve taken a look at the following Messier objects:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

Come back next week for another Messier Monday, where we'll spotlight our twentieth Messier object since we started this series! And for those of you who want some fantastic international news, Starts With A Bang fan Olaf van Kooten has begun translating our Messier Mondays into Dutch over at astroblogs.nl, because the joys and wonders of the Universe should be freely available for everyone to enjoy!

Great post and now it's in Dutch too! Wahoo. I love Mondays.

from the motions of individual stars, we also learn that there’s no supermassive black hole in there

It makes sense that large galaxies would have an SMBH at the center, and sufficiently small galaxies would (probably) not. But does anyone know how steep the transition curve is? IOW, is there some particular galaxy mass at which the probability of finding a SMBH jumps from near 0 to near 1, or is that spread out over a range of masses?

The thing to remember about M33 is that the damn thing is invisible.

Really, the surface brightness is so dim you can't see a sodding thing and the AFOV of anything wide enough to gather a fair bit of light in is so small that your field of view is filled by the galaxy and can't see the edge because of that.

Lovely photographic object.

Complete pants for visual work.

May the lack of a SMBH be related to the lack of a central bulge? I believe bulge-less spirals are thought to have experienced less major mergers. Perhaps less mergers also mean a less massieve central black hole?

But I have another question. Spiral galaxies are believed to have formed from many smaller galaxies. But can (some) spiral galaxies have formed "as is"? I'm asking this, because of the galaxy NGC 2915.

In visible light it's just a normal dwarf galaxy (http://www.astroblogs.nl/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/ngc2915-optisch-500…), however, when you map the neutral hydrogen around this galaxy, suddenly a M33'esque spiral galaxy appears (http://www.astroblogs.nl/2013/01/20/bijzondere-sterrenstelsels-deel-1-h…). Because of the isolated nature of NGC 2915 this gas has yet to collapse into stars, but when it happens, may a spiral galaxy reminiscient of M33 be the end result?

So if there's no black hole, is there a giant star-like furnace at the center of the galaxy?

A star-like furnace? What do you mean?

I love the Triangulum.

"See that line of three stars, with the four around it, and that arc over there? To me it looks like Orion, the great hunter!"

"Ah, I see it! And those stars there that form a cross, doesn't it look like a swan with it's wings spread and neck extended?"

"Oh yes, how beautiful. What about you, Biggus, what do you see?"

"Well... you see those three stars up there?"

"Yeah?"

"Well to me they sorta look like... a triangle."

"..."

What is causing the x-ray source?

Although the actual constellation IS possible to tell from "three stars make a triangle", since the Greek derivation of the name is basically Delta. Which has one fat side when written in script, and the triangulum constellation has (IIRC) three stars at one corner making a sort of sharp bend. As if it were written in scrip with a quill pen.

There are plenty other REALLY STUPID constellations out there.

Aries. Yeah, totally looks like a ram...

Pisces. Uh, you mean a long V with a circle of stars on the end of one of them? And that's supposed to be fish???

On a few, the author really acknowledges that this is all bunkum. Lynx is down as being there by the creator of it "I needed something in that large gap of naff all between the other constellations".

Some are odd (as in don't actually make what they say). Hell I suppose most have that problem, but are still unique and recognisable.

Triangulum, though binoculars especially, is one.

Um yes, obviously Triangulum wins the "Constellation or Asterism That Looks Most Like What It's Called" contest. Not even the Big Dipper has a chance against it.

That's my whole point. Of all the constellations named with imagination and poetic metaphor (and perhaps pharmaceutical enhancement), the namers of Triangulum went for on-the-nose literalism. Sure it's unique and recognizable -- if you know what triangles don't count because they're parts of other constellations. If that's the ideal, let's rename Lyra as "parallelogram plus bright star".

But why stick to cold geometric names when there's no actual physical significance to the arrangement? The poetic names are just fine. Sure Aries doesn't look like a ram, and it takes a fair bit of imagination to see a pair of fish on a rope in Pisces, but so what? You don't learn the constellations by going outside with nothing but a list of the names and guessing based on resemblance.

From my point of view even Lynx is better because sure it's arbitrary but who cares, it at least sticks with the theme of metaphorical representation.