Big Bang

I get a certain question every so often, and it's one of the most difficult questions any cosmologist faces. Today, I try to tackle it. It goes something like this:

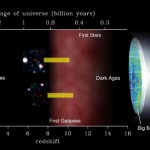

If the Universe is 13.7 billion years old, and nothing can go faster than the speed of light, how is it that we see things that are 46.5 billion light years away?

First off -- and I want to clarify this -- everything in this question is legit.

1.) The Universe is 13.7 billion years old. There are small errors there -- no one would be surprised if it was 13.5 billion or 14.0 billion years old -- but it's definitely not 12 billion…

The last 100 years have brought us from a Universe no bigger than the Milky Way ruled by Newton's gravity to a vast, expanding one with hundreds of billions of galaxies, covered in dark matter, beginning with the big bang, which was likely caused by inflation, and which will end in a freezing cold death as the galaxies accelerate away from one another, off into infinity. We gained and confirmed a new theory of gravity; we learned how all the elements in the Universe were made. We detected neutrinos from an exploding star hundreds of thousands of light years away. And we walked on the Moon.…

We have come so far in the last 100 years, and so has our picture of the Universe. From an island galaxy ruled by Newton's gravity and classical electromagnetism, we've come through the discovery of general relativity, the expanding Universe, the need for dark matter, the big bang, the synthesis of all the elements in the Universe, and, for good measure, we walked on the Moon. By the 1970s, we had a fabulous picture of the History of the Universe.

There's just one (huge) problem: What caused the Big Bang? We know the laws of gravity and quantum mechanics, and we know that the Universe is…

Earlier this week, I wrote about how the heavier elements in the Universe were made. Specifically, that they are made in stars. These stars then explode in a variety of ways, enriching the Universe with these heavy elements, and allowing us to form glorious things, like our planet!

By contrast, the big bang makes light elements, but not heavy ones. Why is this the case, and how do we know? Let's find out.

Image credit: Stephen Van Vuuren, created from a simulation of 80,000 star images.

Just a few seconds after the big bang, the Universe is filled with protons and neutrons, in roughly the…

In the 1940s, the Big Bang theory was first conceived and detailed. But, to quote Niels Bohr,

We are all agreed that your theory is crazy. The question which divides us is whether it is crazy enough to have a chance of being correct. My own feeling is that it is not crazy enough.

One of the staunchest opponents of the Big Bang idea was Fred Hoyle, an outstanding, prolific scientist in his own right.

In the 1950s, Fred Hoyle found it inconceivable that all of the heavy elements in the Universe -- practically everything we find on Earth -- would have been made in the Universe's infancy. He…

By 1948, our view of the Universe had changed drastically from 1909. Instead of space being run by Newton's Gravity, where our Milky Way comprised the entire Universe, we had learned that space and time are governed by Einstein's General Relativity, that our Universe contained at least many thousands of other galaxies, and that the farther these galaxies were from us, the faster they moved away from us. In other words, the Universe was not only vast and full of interesting stuff, it was also expanding as it got older!

The prevailing idea of the day was the Perfect Cosmological Principle,…

One of the most surprising things about the Universe? As vast as it is, it hasn't been around forever. In fact, if you take our plain little rocky home (Earth), it looks like the Universe is only about 3 times as old as we are. It's surprising, considering how huge, expansive, and full of interesting things the Universe is.

And yet, our Sun, Earth, and entire Solar System, at 4.5 billion years, represents a significant fraction of the age of the Universe, about 13.7 billion years.

But how well do we know that number? If you look at the best data, you find that the Universe is 13.73 billion…

When I think of molecules, I think of Conan O'Brien doing his skit where he plays Moleculo...

the molecular man! I don't think of astronomy, and I certainly don't think of the leftover radiation from the big bang (known as the cosmic microwave background)! But somebody over at the European Southern Observatory put these two together and made an incredibly tasty science sandwich.

See, we can measure the cosmic microwave background today, because we have photons (particles of light) coming at us in all directions at all locations, with a temperature of 2.725 Kelvin. Theoretical cosmology…

There is a very techincal paper this morning by Martin Bojowald that asks the question, How Quantum Is The Big Bang? Let me break it down for you.

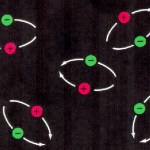

If you took a look at empty space and zoomed in on it, looking at spaces so small that they made a proton look like a basketball, you'd find that space wasn't so empty after all, but was filled with stuff like this:

What are these? They're little pairs of matter particles and anti-matter particles. They spontaneously get created, live for a brief fraction of a second, and then run into each other and disappear. That's what happens on very small…

Since the dawn of time man has yearned to destroy the sun. - C. M. Burns

There's no need to stop at the Sun, though. Since yesterday was Earth day, I thought it was only appropriate to spend today telling you how not only to destroy the Earth, but to effectively destroy the entire Universe. To tell you this story, we have to go all the way back to the beginning, to just before the big bang.

The big bang was when the Universe was hot, dense, full of energy, and expanding very quickly. The Universe was also spatially flat and the same temperature everywhere, and full of both matter and…

What is the future of this website? I'm going to be creating videos for the web about the Universe. I'll be answering questions ranging from what the Universe is like today to how it got to be that way. I'm going to address every step that we know of, from the Big Bang up to the present day.

And I'm going to do it naturally, by telling the story as the Universe tells it directly to us. I call this project Genesis. Check out the teaser trailer below, and tell your friends, because this is coming in January.

There was a paper posted today that I thought was an April Fools' Day joke, entitled Was There a Big Bang? Ha ha, thought I, of course there was; I just wrote all about it two weeks ago. But no, this is a legitimate paper, or at least is attempting to be. (There was even a brief write-up on Universe Today.)

First off, let me tell you who the authors are: two retired scientists who used to work on space missions back in the 1970's. They were instrument guys, taking data and making sure the spacecraft ran. But as they got closer to retirement, they started proposing explanations for cosmology…

This month's issue of Physics Today has an interesting article by Robert Brandenberger of McGill University, entitled Alternatives to Cosmological Inflation. As a refresher, cosmological inflation is the theory that sets up the Big Bang: it takes whatever was in the Universe prior to inflation and expands it away, leaving you with a Universe that has roughly (to a few parts in 100,000) the same properties everywhere, and is spatially flat.

There are many models of inflation which give a Universe like ours, although we have to fine-tune the parameters of it. For instance, if we treat…

I love The Straight Dope. For 35 years, people have written in and asked some of the most difficult-to-answer questions on any topic you can think of; the staffers, writing under the pseudonym Cecil Adams, do their best to get to the bottom of their questions. Well, they also have a message board, and I saw one of the most difficult questions I've ever seen there:

Where does all the matter in the universe come from?

I'm no[t an] astrophysicist but I understand a little about the Big Bang Theory and also that there's lots of stuff we don't know or probably ever will know about it.

But the…

The search for a Theory of Everything, which is kind of the unofficial M.O. of the scientific establishment, has always been closely guarded. The elements of profound uncertainty involved with such a quest have always primly clipped, safe from the grubby hands of untrained speculation. Relatively sane, brilliant physicists who err too far in the direction of the fabulous are practically shunned, or at least relegated to different class; those who posit that any variant of string theory might bridge the gap are nominally demoted from "physicists" to "string theorists," a nomenclature that…

(I know I'm not doing this any more, but I couldn't resist.)

An article in New Scientist reports on musing by two reasonable and respected cosmologists— indeed, ones whom I've met myself— that our discovery of dark energy may have shortened the life of the Universe.

To which I can only say "foo". And I say "foo" on two levels. Primarily, on the sensational way in which this is described by New Scientist. But secondarily, on the interpretations of quantum mechanics that respectable cosmologists are promoting.

First of all, for a bit of perspective. The actual research paper on which this…