The bints, it turns out, have an interesting evolutionary history.

Recent molecular analysis of the order Carnivora (dogs, cats, bears, seals, bints, etc.) places all subsequent species into two clades (branches): the Caniformia and the Feliformia.

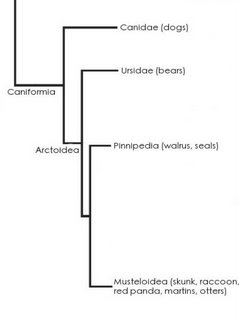

The Caniformia clade contains a staggering array of animals - dogs, bears, seals, martins, pandas, otters and walruses - but interestingly enough, dogs (canids) were the first to split from the group (from the Arctoids), something like this:

The other side of the clade, the Feliformia, starts with the split of Nandinia, the African palm civet. Nandinia was once classified with the other civets in Viverridae, but molecular evidence has placed them in a separate branching.

Here you can see how closely related the bints are to the felids from an evolutionary perspective:

If you consider that the ancestors of the bints arose in the Oligocene, about 30 Mya (about halfway between the dinos and us), that makes the bints are relatively ancient mammals, splitting off with other viverrids from the ancestor of the African palm civet.

During the Oligocene, the world was cooling, but that didn't stop the spread of early forms of extant mammals and the more modern forms of birds:

Early forms of amphicyonids, canids, camels, tayassuids, protoceratids, and anthracotheres appeared, as did caprimulgiformes, birds that possess gaping mouths for catching insects. Diurnal raptors, such as falcons, eagles, and hawks, along with seven to ten families of rodents also first appeared during the Oligocene.

The binturong is the only Old World mammal to evolve a fully prehensile tail, meaning the tail is dexterous enough to be used to manipulate objects, like food items. The rest of the mammals possessing a fully prehensile tail are only found in North and South America (monkeys, opossums).

Only one other member of the order Carnivora has evolved a prehensile tail, the kinkajou (Paris Hilton's old fling).

Next time I want to discuss the ecology of the bints. Unfortunately, that means a revisitation of traditional Chinese medicine.

Resources:

Phylogeny of the Carnivora (Mammalia): Congruence vs Incompatibility among Multiple Data Sets. Flynn J.J.; Nedbal M.A. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, Volume 9, Number 3, June 1998, pp. 414-426(13)

Mosaics of convergences and noise in morphological phylogenies: what's in a viverrid-like carnivoran? Gaubert P, Wozencraft WC, Cordeiro-Estrela P, Veron G. Syst Biol. 2005 Dec;54(6):865-94.

Jeremy, I'm afraid this post might be a little confusing to the layman (supposing any laymen read your blog). For instance, you make it seem as if binturongs are the only viverrids and more importantly, that binturongs themselves have existed for 30 million years. This of course is not true; It seems reasonable to assume the species of the binturong is not older then a few million years at best. Therefore, I think your post would benefit from you pointing out binturongs are just one of many species of viverrid and that it is the viverrids that are some 30 million years old, not binturongs.

Also, (most of) the groups you mention as appearing in the Oligocene, are at least Eocene in age, with the exception of canids and perhaps amphicyonids,tayassuids and the rodent families.

Caprimulgiforms probably originated in the Paleocene, with steatornithids (oilbirds) being known from as early as the Early Eocene.

I think your post might benefit from a few corrections, but do keep up the good work of blogging!

Thanks for the comment, Brian. This post hinges on a couple of previously posted items on the binturong, which go a bit more in detail about viverrids and specifically about the bints. However, if there are still any confused laymen out there, I appreciate that you have cleared some things up for them. :-)

As far as the blockquote about oligocene mammals, it comes straight from the UMCP website; if there are any inaccuracies, perhaps we should shoot 'em an e-mail.

Jeremy, Just found your blog -- Did you forget about the cuscuses? They're old world mammals, albeit marsups, and they have prehensile tails, if my memory isn't failing me. Must read the rest of your binti posts -- used to be a serious enthusiast (well, I still am, actually.) Did you ever notice how they tip their heads back when eating juicy fruit? Nandinia does it too -- obviously it funnels the juice down their throats. Now -- must read the other binti posts!

Chis, glad you enjoy the bints as much as I do! They are interesting critters, definitely off the charts for some people.

I'm pretty sure that all of the species of cuscus are in Oceania, making them a "New World" mammal. It is strange just how many animals in the Americas and Oceania developed prehensile tails compared to the rest of the world.

Here's some interesting zootrivia. Phalanger ursinus is a cuscus that looks a lot like a binturong (same kind of hair) and is relatively large as cuscuses go. A very curious example of parallel evolution. It occurs in Sulawesi (Celebes), west of Wallace's line, which is one island from the bints on Borneo. So it can comfortably be deemed a critter of the Old World tropics (or Australasian biogeographic realm). (The other species of cuscus on Sulawesi is a smaller species, P. celebensis, which bears no resemblance to a binturong). Since bints have also been recorded from Palawan, they've also reached Oceania. My deep memory (which is getting harder to access these days) also tells me that the pangolins of Africa and Asia have prehensile tails (at least the smaller species). You are correct that the only canivorans with prehensile tails are the binturong and the kinkajou, and consequently both are excellent three-point suspension feeders on high hanging fruit!

The "New World" and "Old World" distinctions are so incredibly Eurocentric, I probably should have avoided them in the first place, Chris.

Now the pangolin would be an interesting animal to delve into in a few blog posts...