tags: researchblogging.org, splendid fairy-wren, Malurus splendens,sexual dichromatism, evolution, behavior, promiscuity, social monogamy

Everyone is familiar with sexual dichromatism in birds; you know, the gorgeous, colorful male who is paired with the drab female or two. It has been observed in birds that, when males and females differ dramatically in appearance, the females are preferentially mating with a few "pretty boys"; those that have elaborate plumage colors or ornamentation. As a direct result of female breeding preferences, these "pretty boys" sire more offspring than those males with less colorful plumage, thus driving the evolution of sexual dichromatism in the population. This behavior concurrently drives evolution of a polygynous breeding system in the population. But what about those birds that are monogamous yet still show strong sexual dichromatism? How did they get to be that way?

These are the very questions asked by an American research team. To do this research, the team, led by Michael Webster, who is at Washington State University, conducted a long-term study of the breeding habits of the splendid fairy-wren, Malurus splendens, which is endemic to Australia. The splendid fairy-wren is a very small cooperative breeding species that is apparently monogamous. However, these birds show strong sexual dichromatism; the males have stunning black and iridescent blue plumage while the females are a comparatively drab brown.

There are several hypotheses regarding the evolution of sexual dichromatism, all of which depend upon different numbers of offspring being sired by each male, and that situation is observed under only a few circumstances; (1) if there are fewer females than males in the population, thus limiting male access to reproductive opportunities; (2) if there is a strong difference in female fecundity, thereby allowing some males to sire more offspring with their mate; or (3) if the females engage in promiscuity, thus producing several offspring, some with "extra-pair paternity" (EPP). But until the advent of DNA-based paternity testing, it has been difficult to identify situations where females engage in cryptic promiscuity while remaining socially monogamous.

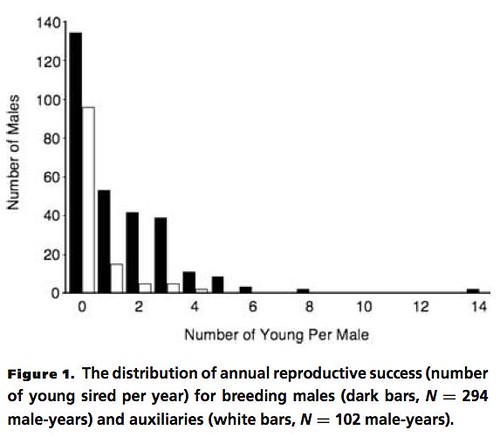

Instead of relying solely on direct observation, the researchers tested these hypotheses by using DNA obtained from blood samples collected from all of the birds in a cooperatively breeding group to identify each chick's father, and they also color-coded each bird with a unique combination of bands so they could be identified with binoculars from a distance. Perhaps not surprisingly, even though these birds appeared to be monogamous, the DNA paternity tests showed that some paired males had a dramatic reproductive success; siring as many as 14 chicks in one case -- ten of which were extra-pair. Interestingly, the team also found that some of the "auxiliary" males, those without mates, also sired some offspring (Figure 1, below).

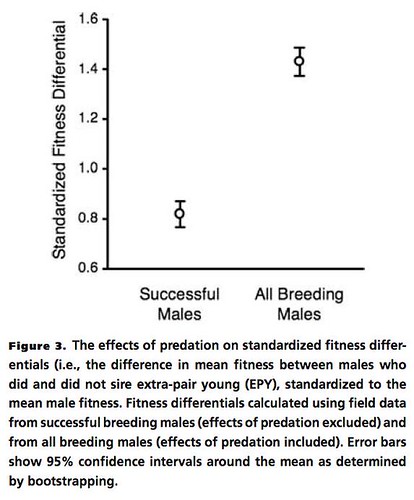

When contrasted with the effects of EPP, the other hypotheses were not important contributors to the overall differences in male reproductive success for this species. Predictably, the effects of nest predation magnified the differences in reproductive success for male birds. Basically, those males who sired the most EPP offspring had the highest reproductive fitness, as expected since they were effectively "hedging their bets" by siring chicks that were located in more than one nest (Figure 3, below).

This research was published in the journal, Evolution.

Source

"Promiscuity drives sexual selection in a socially monogamous bird" by Michael S. Webster, Keith A. Tarvin, Elaina M. Tuttle, and Stephen Pruett-Jones. Evolution 61(9):2205-2211 [doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00208.x]

I love the names of these species, but I'm still waiting to see studies of the Rather Drab Fairy Wren.

Bob

Natural Sciences Carnival 2nd edition is up here and your submission was selected.

Thanks for your submission! Spread the word!