tags: book review, Unholy Business, religious antiquities, biblical antiquities, fraud, Christianity, Judaism, Nina Burleigh

There are two different types

of people in the world,

those who want to know,

and those who want to believe.

-- Friedrich Nietzsche

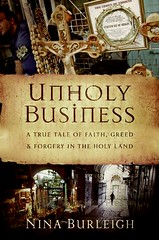

In November 2002, an ancient carved limestone burial box designed to hold the disarticulated skeleton of a dead person was put on public display in Canada's Royal Ontario Museum. Although common throughout Israel, this particular box, known as an ossuary, was unusual because it was inscribed. Even more remarkable, its ancient Aramaic inscription -- "Ya'akov bar Yosef akhui di Yeshua" -- translated to read, "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus." This sent waves of hysteria through the Christian and Jewish communities, causing tens of thousands of faithful to mob the museum. But even before the ossuary was publicly displayed, experts declared the inscription to be a fraud. Unfazed by facts, the religious preferred to believe it was real. In Unholy Business: A True Tale of Faith, Greed and Forgery in the Holy Land (NYC: Collins; 2008), the author, Nina Burleigh, uncovers the trail followed by forged biblical antiquities, from illegal excavations in Israel to a world-class museum in Canada.

At roughly the same time, a stone tablet was revealed to the world. This tablet, which came to be known as the Joash Tablet, was a written record of repairs made to Solomon's Temple, and its wording was very similar to the biblical books of Kings. The Joash Tablet had powerful geopolitical implications because possession of the site where the mythical First Temple supposedly stood is hotly contested by Christians, Muslims, and Jews. Burleigh writes;

According to the Bible, King Solomon built a fantastic temple in Jerusalem around 1000 BCE. Lined with gold, it housed the Ark of the Covenant, the container for God's written word to mankind. The Babylonians sacked the temple in 800 BCE and burned it to the ground. No archaeological evidence of the Temple has ever been found. Also referred to as the "First Temple," Solomon's Temple was later replaced with what is known as the "Second Temple" -- the remains of the platform that once supported this temple are known as the Wailing Wall or the Western Wall -- Judaism's holiest place. Built by Herod, the Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE and never rebuilt. Muslims built a mosque there in the early days of Islam, the Al Aqsa Mosque, Islam's second holiest place. [GrrlScientist comment: this is an error. The Al Aqsa Mosque is Islam's third holiest place, after Mecca and Medina, a fact that Burleigh gets correct later in the book] The site now is one of the most hotly contested bits of turf in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. [p. 16]

In this book, Burleigh follows three forged artifacts; the James Ossuary, the Joash Tablet and a small carved ivory pomegranate (presumably an ornament for a small scepter used by priests in the mythical First Temple). But these intriguing objects fade to insignificance in the first half of the book. Instead, the author focuses on a varied cast of colorful characters involved with biblical antiquities -- millionaire collectors, police, dealers, grave robbers, the devout and a variety of scholars. The book also provides a "reader's digest" overview to the history of the area and the religions spawned there, but includes little depth.

By the second half of the book, some of the scientific evidence is briefly presented and it becomes obvious that the James Ossuary and the Joash Tablet are only the most famous hoaxes. In fact, museum shelves and display cases worldwide probably publicly display fake biblical antiquities to this very day. The author presents this curious mix of science and mythology since it is the devout -- those who accept the existence of Jesus on faith -- who are most enthusiastic in their search to bolster any doubts with physical "proof" of his existence.

I was disappointed by the book's complete lack of pictures, maps and diagrams, all of which would have added much to the story. But Burleigh tries valiantly to compensate with painstaking details of the personal habits (we learn that one person whom she interviewed drinks Nescafe coffee nearly constantly), manner of dress (often comparing people or their clothing style to Indiana Jones) and physical appearances (one person was described -- repeatedly -- as being "bullet-shaped") for all the characters in this story, even minor characters that are mentioned only once. Amusing, but often distracting -- why such intense attention to such trivial details?

This book often reads like a journalist's diary instead of a rigorous expose, but it does tell a compelling, although sometimes convoluted, story. It would have benefited from a careful editing since a few factual errors and repetitions slipped in, as well as some misspellings and strange typographical errors where, for example, all the words in a phrase where squashed together without appropriate spacing. But overall, this book is relatively light and is a fast read, serving as an interesting but brief introduction into the excavation of ancient artifacts in Israel, the modern biblical antiquities market and the history of the Holy Land. Burleigh's book also raises important questions about the limits of faith and science in understanding human history and the material world.

Nina Burleigh is an adjunct professor at Columbia University's Graduate School of Journalism. She began her career in journalism by covering the Illinois Statehouse for the Associated Press. She has written for the New Yorker, New York Magazine, Time, People, The Washington Post and numerous national magazines, and is an occasional blogger on The Huffington Post. She has written three other books; Mirage: Napoleon's Scientists and the Unveiling of Egypt (NYC: Harper Collins, 2007), The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America's Greatest Museum: The Smithsonian (NYC: Morrow; 2003), and A Very Private Woman: The Life and Unsolved Murder of Mary Meyer (NYC: Bantam; 1998). Nina is married to photographer Erik Freeland, and they and their two children live in New York City.

I live in the Toronto area, and I recall no hysteria or mobbing of the museum. I recall interest and scepticism (even before the expert pronouncements). And saying that the religious preferred to believe it was real makes little sense. If you believe in the resurrection, what's the point of an ossuary?

If this paragraph is representative of the approach, it sounds like a book to avoid.

Arrrrggh! Hit "Submit" too soon.

I realize that the ossuary was supposedly of the brother of Jesus, but the only really odd speculation I recall was that perhaps Jesus's ossuary would be nearby. And that of course is something more likely to occur to a non-believer.

Given the fairly convincing debunking that had taken place before the display, I recall the whole thing as a bit of an anticlimax.

Scott, it doesn't matter that the debunking occurred at all - the initial publicity by the believers is still widely believed by the public.

Almost no public attention has been given to the debunking as opposed to the tv shows, magazine coverage etc. the original 'discovery' got.

And the BAR continues to stand by the authenticity no matter how much evidence piles up.

I would have preferred photos of the forgeries and an explanation of how bits were determined to be forged. For example, with James' ossuary, there was a mixture of ancient engraving and new engravings; the interesting story is how that can be known (and why the best of forgers fail to fool people who know what they're doing).

As for the Temple of Solomon, a century or so after the Roman rulers ordered its destruction, a christian temple was built on the same hill. Remnants of the lower parts of the christian temple can be seen through one of the current muslim buildings on the site; I can't remember if it's via the Al Aqsa mosque or one of the other buildings. Many remnants of walls of the Jewish temple still remain on site and to some extent archaeological digs are permitted in places.

Thanks for the review - it sounds like a book to avoid. Such a pity really; I would have been far more interested in details of investigations of antiquities rather than the boorish world of art theft. Some people have far too much money on hand; such people pay for the theft of rock carvings, rock paintings, entire (large) altars from old churches, idols and icons, and of course even the occasional Munch, Van Gogh and so on. I think it's far more interesting to learn about how fakes are discovered than to hear the same tired stories about theft and forgery. After all, people have been robbing the Egyptian pyramids for over 4000 years.

Rob, I don't recall any television coverage about the discovery without the debunking involved. In fact, it seemed to me that most networks were eager to debunk.