I've written before about the problem of the Ph.D. glut, so I was pleasantly surprised (shocked, actually) to read several articles in a recent edition of Nature hitting the same themes. For those who don't think there's a Ph.D. glut, here are some data for you:

Post-doc numbers shouldn't be increasing, unless there's a glut. While Nature accurately identifies the problem, they fall short in explaining what's driving it. But I'm getting ahead of myself. Cyranoski et alia:

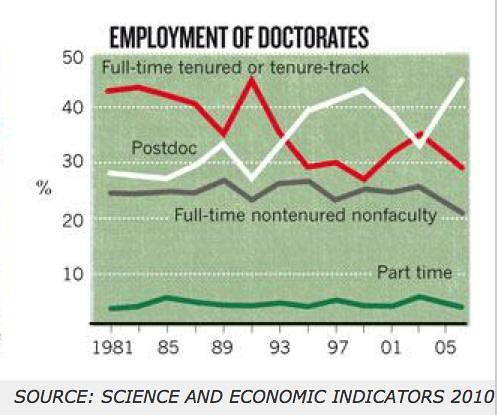

The proportion of people with science PhDs who get tenured academic positions in the sciences has been dropping steadily and industry has not fully absorbed the slack. The problem is most acute in the life sciences, in which the pace of PhD growth is biggest, yet pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries have been drastically downsizing in recent years. In 1973, 55% of US doctorates in the biological sciences secured tenure-track positions within six years of completing their PhDs, and only 2% were in a postdoc or other untenured academic position. By 2006, only 15% were in tenured positions six years after graduating, with 18% untenured (see 'What shall we do about all the PhDs?'). Figures suggest that more doctorates are taking jobs that do not require a PhD. "It's a waste of resources," says Stephan. "We're spending a lot of money training these students and then they go out and get jobs that they're not well matched for."

I think I've mentioned something about training not matching jobs. Maybe. And the editors of Nature note:

But there are reasons for caution. Unlimited growth could dilute the quality of PhDs by pulling less-able individuals into the system. And casual chats with biomedical researchers in the United States or Japan suggest a gloomy picture. Exceptionally bright science PhD holders from elite academic institutions are slogging through five or ten years of poorly paid postdoctoral studies, slowly becoming disillusioned by the ruthless and often fruitless fight for a permanent academic position. That is because increased government research funding from the US National Institutes of Health and Japan's science and education ministry has driven expansion of doctoral and postdoctoral education -- without giving enough thought to how the labour market will accommodate those who emerge. The system is driven by the supply of research funding, not the demand of the job market.

But the Cyranoski article hints at the fundamental problem:

Anne Carpenter, a cellular biologist at the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is trying to create jobs for existing PhD holders, while discouraging new ones. When she set up her lab four years ago, Carpenter hired experienced staff scientists on permanent contracts instead of the usual mix of temporary postdocs and graduate students. "The whole pyramid scheme of science made little sense to me," says Carpenter. "I couldn't in good conscience churn out a hundred graduate students and postdocs in my career."

But Carpenter has struggled to justify the cost of her staff to grant-review panels. "How do I compete with laboratories that hire postdocs for $40,000 instead of a scientist for $80,000?" she asks. Although she remains committed to her ideals, she says that she will be more open to hiring postdocs in the future.

Nature incorrectly believes that too many Ph.D's is a bug, not a feature. That's wrong: neither research universities nor funders think the Ph.D. glut is a problem.

From the funders' perspective, why should they pay a salary of $80,000, when they can get the same help scientist for half the price? On many grants, especially those given to individual labs ("R01s"), personnel are already a huge cost--often over half of the direct costs (the non-overhead/fringe benefits budget) of the grant. If we assume a fixed amount of money, then funders will have to cut back on the number of projects they can support. Of course, overhead/indirect costs could be lowered too.

But all of those scenarios are bad for universities dependent on research largesse. I've conservatively estimated before that roughly 15% of total federal grant dollars (direct plus indirect costs) are 'profit'--they don't support the costs of research or actual overhead costs (administration, keeping the lights on, etc.)*. Fewer grants means that there's less opportunity for overhead dollars. Even if a university (or more accurately, the faculty) can keep the funding level constant with fewer, larger proposals, this is far less cost-effective: you have a high faculty-grant dollar ratio.

Keep in mind, if a high-powered research university loses $20 million dollars of this 'overhead profit', this has to be made up somehow. One way is to 'dedicate' $400 million to $500 million of endowment every year to make up the shortfall (four to five percent interest on that sum). Alternatively, tuition or other fees can be cranked up. Of course, faculty could be laid off, but then people complain about class sizes and so on.

So I agree with Nature: creating Ph.D's without any idea of how they'll be employed 'post-post-doc' is bad policy. It's a good argument for a research center model. But the impetus to change won't come from funders or universities-they're too dependent on the status quo.

*'Profit' doesn't mean they're spending the money on pornstars and coke (WINNING!). But the money can supplement the general budget (or departmental budgets).

The base problem is that to many Phd's are created. For each faculty member in a research university the graph suggests no more than 3-4 grad students in an entire career. Implying that there will be gaps when the faculty member has none, assuming a 30 year career, and 4 years of active supervision of a grad student. This birth control would as noted greatly change the model of the research university, and might result in a number of universities dropping programs in subjects. In essence you need to decide the total number of Phds needed, then how to partition them among schools.

An interesting question what was the number of grad students per professor between 1918 and 1938?

From a brief (and beer-infused) interchange with a couple of faculty members last week regarding this Nature series (which neither had read, to be clear), I came away with one constant. Besides your correct interpretation that the research center model gives them incentive to continue this, I was basically told:

"This is baseball. Major league baseball. The few and the talented will make it and the system is designed to weed out the rest who don't want to compete to the end and be the best. There's no crying in baseball."

The institutional funding policies are one thing, but the baseball analogy is tough. Yeah, intense competition breeds better faculty members. But it's also hard to defend a system with a 90% attrition rate, especially if those who fail aren't being picked up by other careers and are poorly trained for the outside world.

I doubt I can find it today, but there was an article in Bioscience around the late '70's which characterized the history of science in the USA using the sigmoid growth curve. The article documented doubling of science funding during the logistic growth phase. It argued that funding would never double again, and that carrying capacity (zero growth, steady state) had been reached and overshot. Predictions of no new large labs, and decreased number of science PhD programs were based on this model. As I recall they argued for less than one biology PhD program per state. This obviously has not happened, and here we are today.

The main problem is the thesis that 'science' PhDs are only useful for academic or industrial practice of science. There are so many jobs and/or employees that need the expertise that comes from a few extra years of analytical training and other rigors (writing and communication of science, science-based understanding/search for truth) of grad school and a post-doc. Patent law, technical writing, science publishing, management consulting, ...

"This is baseball. Major league baseball. The few and the talented will make it and the system is designed to weed out the rest who don't want to compete to the end and be the best. There's no crying in baseball."

I'd buy this explanation, almost completely, except for the fact that people in the system only realize that science research is "Baseball" when they're over halfway into it. At least with real baseball, it's well understood only the best of the best make pro.

I think a huge part of the problem is that graduate programs currently take far too many students and the quality of students is poor.

Many labs in my department routinely take students that they can only afford to pay if the students remain on a teaching stipend. These students typically take longer to graduate and get less done. They then go on to a lower tier postdoc or a job unrelated to the field. Needless to say, it's fairly obvious well within the 1st year who's going to actually graduate much less make a faculty job. Maybe we should start taking in less graduate students as a way to start fixing the problem.

I think Joe H. and JMG are on the right track. Perhaps this is a high-pressure field, with only a certain amount of room at the top, and there's little we can do to change that without some sort of unrealistic national top-down control.

What really needs to change is the communication between the science community and the prospective scientists. Let them know their odds well in advance. Don't sugarcoat it because you want more cheap labor. If they still want to take the chance and believe they can outcompete for the jobs, then so be it.

We'll still have a ton of graduate and post-doc labor, and the jobless ones will have been duly warned.

I like the whole "no crying in baseball thing". One important point to make is that students can pick career paths, and if a science career looks like it sucks, the top students will go somewhere else (MBA, med school, etc). Look, here's a study that says exactly that! http://www.sciencemag.org/content/326/5953/654.1.full

Jake Locker was drafted in baseball. He said, "why would I want to slog though the minor league system for a chance to play a crappy game?" Now he's been drafted #8 in the NFL draft--he's going to make bank and will almost surely get a shot at being a star.

At some point, a science career is going to be a cutthroat way of determining the best C-student, because all the A's and B's are off enjoying their lives and nice careers.

With the caveat that the plural of anecdote is not data, the frau (a PI at a prestigious Ivy) and another PI (at a prestigious research institute) constantly lament they are not teaching future scientists but rather training future employees at McKinsey and the like. So even when the student makes the slog through the PhD, there's no guarantee they will stay in it.Indeed, the best C student is what coming through the pipeline. Success is not the result of meritocracy, more the outcome of cronyism and nepotism.

The problem with "science as baseball" analogy is the underlying assumption that a system based on fierce, cutthroat, ruthless competition produces the optimal result in an academic context.

Moreover, the whole "science as baseball" analogy is mostly wrong anyway. Its no longer "science as baseball" (that was in the 1960s), but rather "science as sweat shop labor". The system isn't designed to select the best, its designed to generate hoards of low paid, hard working postdocs to do the grunt work. Invariably, some of these will be satisfactory enough to take over as professors and produce the next generation of toilers.

The other problem with the "science as baseball" model is pretty obvious and critical: the expected value. People dedicate their early lives to baseball because of the possibility of a huge payoff. Well, making 25% less than industry as a tenured professor after 1-2 decades of 70 hour weeks, with a 85% chance of failure, is not going to attract the vast majority of highly intelligent, rational people. This is especially true since students see that their tenured professors are still constantly struggling as grant writing managers, and never have the time to do any research anyway.

Instead, what you find is that the quality of American PhD students has plummeted. You have bright Indian and Chinese students who still see the $40,000 postdoc as a goldmine, but sensible westerners have already abandoned the academe.

There will always be a small minority of people that is so dedicated to science that they will enter the PhD pipeline and stick it out until tenure at age 45. Moreover, the huge supply of Indian and Chinese students keeps the system alive and "healthy" today. But in the short to medium term, you will see that American students will increasingly shun graduate school, until the system is completely "out sourced".

Is this a problem? Well, maybe not, so long as all of those foreigners don't return home. But as China and India continue to develop, more and more of them are deciding to head back. Furthermore, many critical US government programs require US citizenship for national security reasons. The end result is that in the next 10-20 years, we may find that the old PhD->post doc->professor model isn't giving the US tax payer a fair return on their $ Billions.

University professors are like addicts (except in math and perhaps in physics) they are hooked on post docs and RAs to write papers for them. They begin to lose their focus writing so many grants, dealing with so many people and teaching. They need more and more of it, they get Indians, Chinese more and more. They offer them phds when they have done enough indentured work. There is no failure just do the time and you get. Then same professors tell Congress not to tighten h1bs and green cards because there is "shortage" lol. It is like a racket with super smart people running it: the university educational complex.

Being an academic in the purest sense is often like masturbation. You think that you are making effectual contact with the real world, but in reality it is just a fantasy in your head, and a pencil in one hand.

University professors are like addicts (except in math and perhaps in physics) they are hooked on post docs and RAs to write papers for them.