"A sister is both your mirror - and your opposite." -Elizabeth Fishel

With 110 deep-sky wonders to choose from in the Messier catalogue, our long-running series on Messier Monday promises to keep us busy for some time to come! As we've finally passed the winter solstice here in the Northern Hemisphere, many new spectacular sights await skygazers in the early part of the night. As it's also the 1-year anniversary of when we adopted a little sister for our dog from the local humane society, I thought it would only be fitting to highlight the little sister to last week's Messier object.

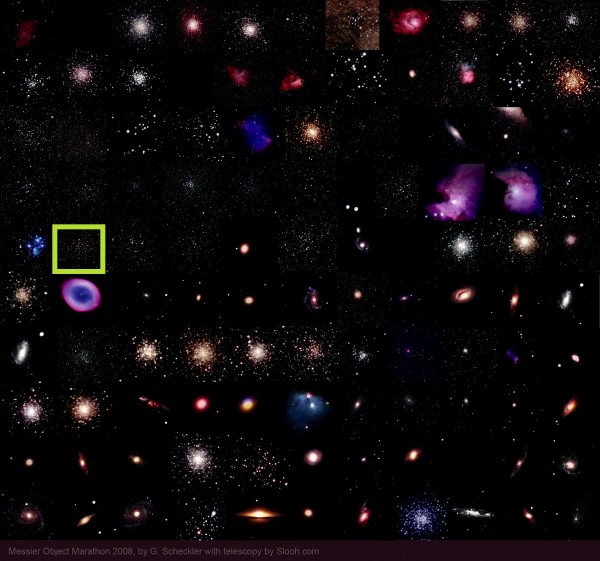

Image credit: Greg Scheckler (http://gregscheckler.wordpress.com/blog/) with telescopy by Slooh.com.

Image credit: Greg Scheckler (http://gregscheckler.wordpress.com/blog/) with telescopy by Slooh.com.

Last week, we took a look at Messier 47, a relatively nearby, young open star cluster that rises shortly after sunset at this time of year, trailing a little bit behind Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. But just a single degree away is this week's object -- Messier 46 -- which appears at first glance to be a dimmer, less spectacular 'sister' cluster.

Is that the truth? Let's show you how to discover it and then find out together!

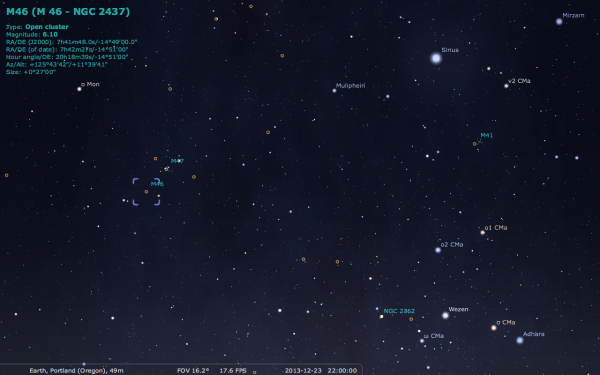

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

As we approach the new year, Orion can be seen flying higher in the sky earlier and earlier in the night, trailed by Sirius and -- a little bit later (and lower) -- the slightly more southerly bright pair Adhara and Wezen. Right next to Sirius is the quite bright (at magnitude +2) star Mirzam.

If you draw an imaginary line from Mirzam to Sirius and another from Adhara to Wezen and extend them both, where they meet is approximately where Messier 46 lies.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

There are really only about three stars in that small region that are clearly visible to the naked eye, but through binoculars or a telescope, there are quite a few deep-sky objects in that region of sky. This is no surprise for a location that looks into the galactic plane like this, and the dominant deep-sky object is last week's Messier 47. Just a little bit south of that cluster, however, between the naked-eye stars 4 Puppis and HIP 37379, lies a dimmer, smaller cluster: this week's object, Messier 46!

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

It's easy to overlook this cluster when compared to the bright, blue beauties just to the north of it, but if you take a closer look at what might -- at first glance -- appear to be a non-spectacular object, you'll be glad that you did.

Image credit: W. Garrett Grainger, Jr. of http://www.beachastronomy.com/.

Image credit: W. Garrett Grainger, Jr. of http://www.beachastronomy.com/.

Standing out clearly against the galactic backdrop, these stars may all appear faint, but are they really? Messier described them so:

A cluster of very small stars, between the head of the Great Dog and the two hind feet of the Unicorn... one cannot see these stars but with a good refractor; the cluster contains a bit of nebulosity.

But even though Messier was wrong about this cluster in a whole slew of ways, it's easy to understand when you look back with 242 years of hindsight since its discovery.

Image credit: Kfir Simon of Pbase, at http://www.pbase.com/image/133973249.

Image credit: Kfir Simon of Pbase, at http://www.pbase.com/image/133973249.

Although it might seem wimpy compared to it's brighter sister cluster in the sky, Messier 46 isn't made up of small stars, nor does it have any nebulosity inside of it. Instead, it's one of the most distant open clusters in the Messier catalogue, located over 5,000 light-years away!

And one of the main reasons it appears to have so many stars prominently displayed in there is because the brightest classes of stars -- the O and B stars -- have all run through their entire life cycle and died by this point.

Image credit: Unknown, retrieved from http://www.docdb.net/show_object.php?id=ngc_2437.

Image credit: Unknown, retrieved from http://www.docdb.net/show_object.php?id=ngc_2437.

That leaves a cluster dominated by A-class stars, which are still blue and bright, but much less so than its shorter-lived brethren. All clusters, when they're born, are thought to contain stars of all types, with the brightest and most massive stars running out of fuel fastest. From the stars that still remain in M46, we can tell it's about 300 million years old, an intermediate age for a star cluster.

Image credit: © 2006 - 2012 by Siegfried Kohlert, via http://www.astroimages.de/.

Image credit: © 2006 - 2012 by Siegfried Kohlert, via http://www.astroimages.de/.

A closer inspection -- one that brings out more colors and the fainter stars -- can reveal that there are around 500 stars identifiable in this cluster, including many that are dimmer and redder (in addition to a small number of giant stars) than the Sirius-like A-stars.

Image credit: Roy Uyematsu of http://www.roystarman.com/.

Image credit: Roy Uyematsu of http://www.roystarman.com/.

There could, of course, be even more stars located in this 26-light-year-wide spherical region; infrared observations -- as they often do -- highlight a somewhat different stellar population than what we see with visible light images.

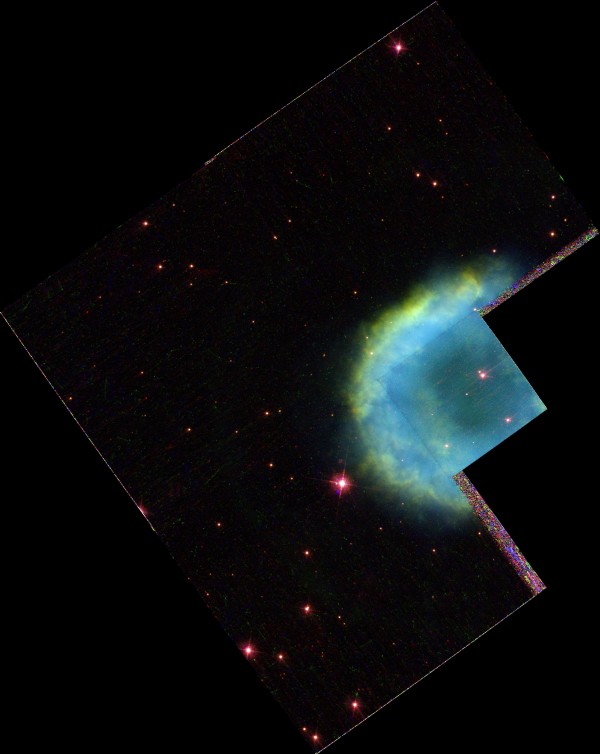

In addition, you may be noticing what looks like a familiar shape: a ringed nebula around one of the stars! In fact, there is a planetary nebula there, a remnant of a dying sun-like star going through its death throes, blowing off its outer layers and contracting its core down to a white dwarf.

But, is it connected to the cluster, or is it merely a foreground object?

It's hard to tell from just the optical image, isn't it? Although you might intuit that the apparent reddening of stars around the planetary nebula is indicative that the stars are behind the nebula, that doesn't tell you whether this is a foreground object or whether this nebula is merely towards the "near side" of the cluster.

If we want to know for sure, we have to measure the redshift of many individual stars and the planetary nebula.

You see, open star clusters are very tenuously bound, and stars contained inside one all have approximately the same redshift, as even small changes in a star's velocity would cause it to escape from the cluster. Well, the stars in the cluster are receding from us at 41.4 km/sec, but the nebula recedes at 77 km/sec, so it's not a part of the cluster after all!

Our best estimates, in fact, place it at a mere 2,900 light-years distant, much less than the estimated 5,400 of today's cluster!

The shame of the more distant star clusters is that they're often obscured by the disk of the galaxy, and that it's increasingly more difficult to bring out the fine details in them. But, it is easier to fit the entire cluster into a high-magnification field-of-view, which makes it very easy to view the entire thing at once!

Image credit: © 2012 Louis P. Marchesi, of http://astronomiae.com/.

Image credit: © 2012 Louis P. Marchesi, of http://astronomiae.com/.

This cluster is large, massive, and has all the right ingredients to make it to a billion years or more intact, a bonafide rarity for an open star cluster! Enjoy this less well-known sight all winter long, but feel free to start today, as we wrap up the year's penultimate Messier Monday! Including today, we’ve looked at the following objects:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The 'Little Sister' Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Come back next week, where another deep-sky wonder -- and another tale that the Universe tells us about itself -- awaits you, only on Messier Monday at Starts With A Bang!

Fascinating and beautiful piece here - love the images and the chosen words explaining them. Thanks Ethan and merry Christmas / happy holidays -enjoy the days and make of them what you want, hopefully something good.