There are two mistakes one can make along the road to truth... not going all the way, and not starting. -Siddhārtha Gautama, a.k.a. Buddha

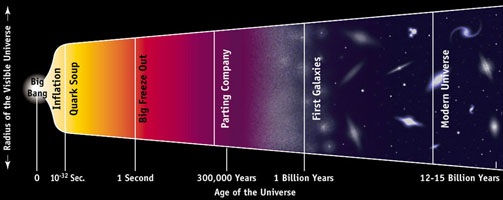

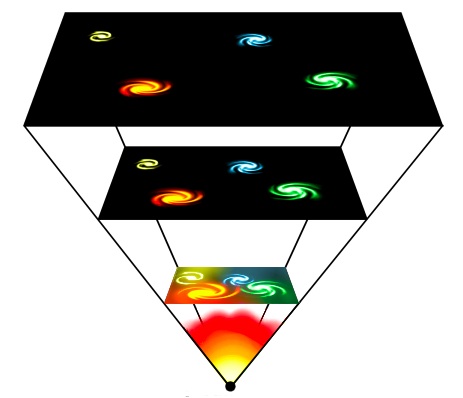

Last week, I started a new series on The Greatest Story Ever Told, about the origin and evolution of the Universe. In it, I asserted that inflation is the very first thing we can definitively say anything sensible about, and that it happened before the big bang. This runs contrary to a lot of statements out there by a lot of reputable people, including this "timeline" image from Discover Magazine:

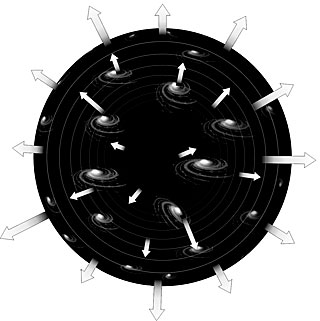

Everything else aside, it's very important to remember where the idea of the Big Bang comes from. What we see today, when we look out at the Universe, is that the farther away things are from us, the faster they move away from us.

The Big Bang, an idea dating back to the 1940s, was a brilliant extrapolation of this idea. If the Universe was smaller, denser, and hotter in the past, George Gamow and his collaborators stated, then a few very interesting things happen.

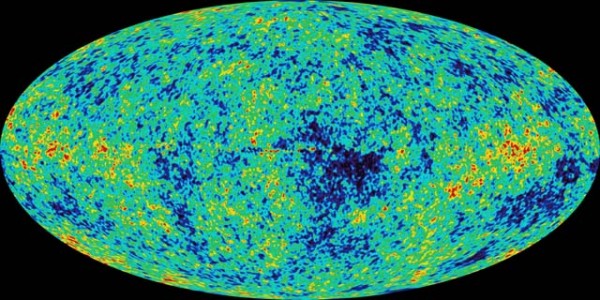

Far enough in the past, the Universe must have been hot enough to prevent the formation of neutral atoms. If this were true, we should see the leftover radiation that kept the Universe ionized at this time. We not only discovered this, we can measure the temperature fluctuations in this Cosmic Microwave Background, and show them to you.

As you travel further back in time, more interesting things happen at higher and higher energies. (A good part of the new The Greatest Story Ever Told series will be taking you through what those things are and when they happen.) When the big bang was first conceived, the extrapolation went all the way back to a singularity, when all the matter and energy in the Universe was concentrated at a single point, where the expansion was arbitrarily fast, and the temperature was practically infinite.

But when inflation came along, all of that changed. No longer could we extrapolate all the way back to a singularity. If we wound the clock of the Universe backwards, we would discover something remarkable. At some point, about 10-30 seconds before we would anticipate running into that singularity, the Universe instead would undergo inflation (in reverse, if we're looking backwards), and we have no evidence for anything that came before it.

The Big Bang, instead of being a singularity, is the set of initial conditions of an extremely hot, dense, expanding Universe that exists immediately after the end of inflation.

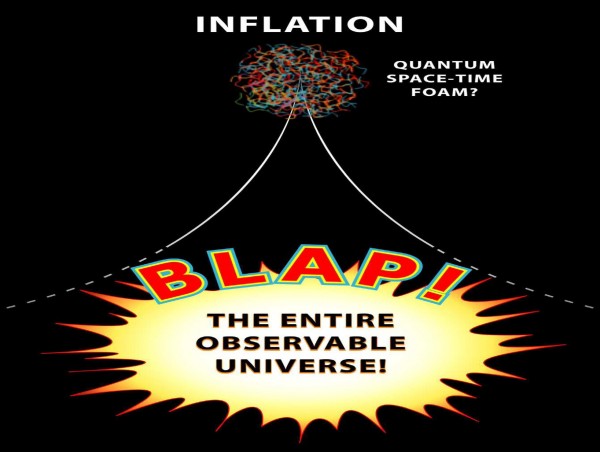

Was there a singularity before inflation? Possibly, but at this point, we have no way of knowing. Inflation is the first thing we can say anything definitive about, but it definitely comes before what we traditionally call "The Big Bang". So maybe I should admit that Starts With A Bang isn't really the starting point of everything, after all, just the start of where our observable Universe comes from.

But the answer to our Q & A for today? Yes, inflation happens before the Big Bang, and ever since its acceptance, has removed the necessity of a singularity at the start.

Was/is there a constant speed to the expansion of the universe? If so, what actually propels the universe to do so? What pray tell, is on the opposing side of the ever expanding universe? Is it empty space? How is one to know?

I agree 'Starts with a Bang' sounds catchier than 'Starts with Inflation' ;)

But didnt inflation inflated the universe to 'bigger' than the observable universe now? If so why was it still 'hot and dense'.

Thanks Ethan for the clarification.

I have to say though, reading this makes me very sad and disappointed. How is it that I can misunderstand something so basic for so long? Despite reading so many articles on the subject. Should I crawl under a rock in embarrassment for misunderstanding? Should I have little confidence in the articles I read? What about other branches of science?

Now that's a brain twister right there! Thanks Ethan for explaining it.

If you were at the end of inflation, could you see back before inflation? Or if you were at 10^-30s, could you look back in time?

In short, is the limitation of "not being able to see before inflation" a limitation of our current point in time -- or is there some hard wall at 10^-30s that essential divides the universe in two, timewise? How could it be that there isn't some continuity in information between the two "halves", regardless of whether that information has been lost in the intervening time? Or if lost, how have we lost that resolution?

I'm still curious what the mechanism for Inflation could be?

I've long been fond of identifying "the beginning of our Universe" to be "the end of inflation".

I'm not sure that I'd say that that end was the big bang, though, because it was probably a kind of roll-off, not an actual "moment" of bang. My own position is that the Big Bang is a poorly named theory because there's no moment of Bang, and because what it really describes is everything that happened since that high-density, hot initial condition.

I'm thinking this is where astronomers and geometers parts ways. From my perspective, you may as well say that "we have no evidence for what's inside a black hole, so we don't care about singularities contained inside."

Any geometer will show a trapped Cauchy surface leading to a future singularity, or whip out the Schwarzchild solution; and all popularizers still tell vivid tales of what happens once past the event horizon. The geometry says something, even if the phenomenology sits mute.

Is BLAP! an official term of theoretical physics or a term of cosmology?

Big Blap is the new Big Bang.

I still say, as a descriptor, "Big Bang" is more appropriate to that small interval that marks (or seems to mark) the beginning of inflation. What we interested laymen want to know is what happened "at the beginning." Are you saying that the period of inflation was not "our universe"?

Ok now, I'm still confused. I can grasp that we can't see behind the inflationary stage of the universe, but I'm not getting why the big bang (as was previously understood to be a singularity) thus had to occur after inflation. Would it not be more proper to say that you're redfining what the "big bang" is as something that is NOT a singularity? If it is so redefined, then what remains of the previous understanding of the big bang?

This is fascinating! Thank you.

@Sachi, it does seem that he's redefining "big bang" to be essentially the end of the radiation-dominated "opaque" era of the universe. At which point I say that the term has been stretched beyond all possible meaning (sort of like string theory has). I really can't see a good reason beyond the fact that the lay public knows the term "big bang" and presumably cosmology popularizers don't want to give it up.

Is there any evidence/theories that would suggest that the matter from our universe dispursed during the big bang was accumulated in a super massive black hole that consumed so much matter/enegery it exploded by exceding some sort of maximum storage capacity?

Or suppose the expanding universe is just the back end of a supermassive black hole that is continually spewing out its lunch? Perhaps we are the poo thats being dumped out of the backside of a black hole? Obviously I dont have much knowledge on the way black holes function, but I would like to know more.

Is there any merit or consideration being given to these possibilities? I'm sure someone some where has had the same thought. Was curious to know if there were any conclusions drawn from such an idea(s).

Check this out and we might be looking at the universe a little differently in the near future:

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=splitting-time-from-sp…

Another school of thought...

Einstein wrote his now well recognized E=MC2, but

I like to write it as E/M= C'(the not really so constant speed of light)squared and start with E/M = 1. Speed for anything is always simply a matter of distance/time or if you prefer, a specific distance for a specific time. If you solve for all possibles of distance and time for the Deltas thereof including the imaginary ones, a four point vector defines a specific point within any three dimensional (real) space. So, if at the "speed of light" E/M is (also) equal to "1", then where are we?

Here's my blog piece from several years ago about why I think that "Big Bang" is a bad name for the theory: http://www.sonic.net/~rknop/blog/?p=108

"Big Bang" is the name we give to our current overall model/theory for the Universe. It started in an extremely hot, dense state, and condensed from there. But the theory as it exists today does *not* include a "moment of bang"-- that goes into the "we dunno" part that you need quantum gravity to understand. Unless you do something like what Ethan is doing here-- define "the beginning" to be "the end of inflation", and then our theory can include "the beginning". But there's no singularity.

Did the Universe start in a singularity? Probably not-- even though that singularity from a classical extrapolation backwards shares the name with the theory. Generally, when your physical theory predicts a singularity, it means that you've extrapolated your physical theory past the realm where it applies. (That's also my reply to John @7. Sure, the geometry says that there must be a singularity in there... but what is probably really going on is that the Riemann geometry which, according to all experimental tests is an excellent description of gravity where we've been able to test it, is not the ultimate truth of what's there, and breaks down as a description of reality as you get close to the core of a black hole, because of quantum effects.)

I can understand why inflation is needed before the BB, And I except an ever expanding universe of galaxies. However, we see the condensing of galaxies at the same time. Does that not indicate the contraction of space between the galaxies? If enough matter is condensed into massive black holes will not the geometry between black holes have the effect of a forever expanding and eventual contraction to a universal singularity?Picture galaxies walking up a ever lengthening down running escalator where the increasing mass of the galaxies causes the advancement on the expanding escalator to slow to a steady state and then reverse progress and pile up at the foot of the escalator.

Is it not possible that we live in a dynamic universe where expansion,steady state and contraction all have meaning? Where the steady state will be just as fleeting as the initial singularity?

We see the recycling of systems all throughout physics, why would the whole be any different than the sum of it's parts?

Is there any reason to think of "dark energy" as different in any fundamental way from "inflation"? Or is it just a matter of branding: inflation is old and familiar, where dark energy is new, different, and eminently more fundable?

Nice explication. Thanks for posting it.

How about "Starts with a Breath"? Or is that a little too Hindu?

Finally, "Blap, the entire visible universe!" I don't know if Aristotle would have agreed; but I think you have well summarized the state of scientific knowledge about the origin of the visible universe.

Conveniently you've thrown many of the preposterous extraordinary assumptions into the dumpster of the cosmic inflationary hypothesis, which metaphorically is kind of like a black hole in reverse (with or without a general relativity singularity). My suggestion, keep throwing.

Even without the inflationary hypothesis; I don't accept most of the remaining "big bang" theory as described. Let me use Ethan's words from SETTING THE COSMIC DISTANCE RECORD to argue my point.

Ethan say, "At a redshift of eight, it's the most distant object ever discovered. This was light emitted around 13 billion years ago, when the Universe was less than one billion years old. And yet, looking at the spectrum of this one, it's still full of heavy elements!... And the continued observation of this Gamma-Ray Burst confirms that, despite occurring 95% of the Universe's lifetime ago, the Universe was very, very similar then to the way it is now. The same stars, the same stuff, the same explosions as the ones we see now. There's never been a more distant, more comforting observation than this, that tells us pretty much exactly what we expected."

So I'd throw out most hypothesizing before the "cosmic distance record" into the cosmic inflationary dumpster and I'd pay a lot more attention to the idea that "the Universe was very, very similar then to the way it is now."

As for the current CMB interpretation, I don't think it is any better that the many others fallen CMB hypotheses. I think the temperature implied by the CMB is an important clue to something other than the important mystery of the "apparently" expanding universe.

As Hubble said, "Redshifts may be expressed on a scale of velocities as a matter of convenience... The term "apparent velocity" may be used in carefully considered statements, and the adjective always implied where it is omitted in general usage." Though much has been observed since Hubble; I think he was correct in his caution inclusion of the adjective "apparent".

Finally, let me mix metaphors. Observations of light emitted by stars over the last 13 billion years have been Turtles all the way (i.e heavy metal stars). However, current theory predicts that before 13 billion years it was non-Turtles non-heavy metal stars) all the way back. I disagree and predict that the spectrum of light emitted from the star that breaks the current cosmic distance record will be Turtles. Further, I predict the continued observation of Turtles at 13.1 billion years, 13.7 billion years and so on. I await spectral analysis of the next Cosmic Distance Record.

Perhaps the faster than light inflation of the universe makes up the majority of a universes 'lifespan'? The physical laws and apparent environment during that period being the 'norm', might it be that the universe as we know it runs backwards to us? Imagine vast regions of space flooded with energy compressing chunks of matter into 'stars'. These stars suck more energy out of their surrounding space while breaking down complex matter into hydrogen before gently dispersing it out into the cosmos...

For some reason the life of a star makes more sense to me in reverse!

(I think my mind may have melted..)

Another way of thinking of it may be that inflation IS the big bang.

It may be quite irrelevant to discourse on the subject that has not been physically witnessed and/or certainly measured with absolute value, such as time.

Our civilization based on our current science level may be well off contemplating on the physical nature of infinit matters, if the realm of our science can accept the existence of infinity. Simply, no so-called scientist seems to have challenged to define the outside of the big bang. Without substantiating the basic nature of what is "inside (big bang, etc.)" and what is "outside", we may miss the chance to advance ourselves to the next level of our Darwinistic evolution - and end up in the same old man kind history.

I beg our fellow scientists to, first admit this simple fact of us human not being able to comprehend the infinit nature of the space. I think, everything starts from there.

Intellexus

I would like to also add that Hobble was great to bring us finer images of the universe, and ability to see partially how the universe was created. Here's a question: why do we not hear anything about what was "before" the universe was created? Is it a too complex matter for the existing human knowledge and ability to even hypothesize?

It seems to me that our understanding of the universe may not have to be dependent on how accurate and high performance we can build our telescope.

Is it possible that gravity has helped slow the expansion of the universe? Is it possible the larger the universe becomes, the less effect gravity has to slow the expansion? Is it possible that some force outside the universe is pulling and expanding the universe?

@John Armstrong:

I’m thinking this is where astronomers and geometers parts ways.

Not really. The singularity theorems of Hawking and Penrose only work assuming that matter has positive energy and pressure.

Inflation assumes that space was pervaded by "vacuum energy" with negative pressure => Singularity theorems break => Universe might not have started with a singularity.

"Was/is there a constant speed to the expansion of the universe?"

No.

" If so,"

Void.

"why do we not hear anything about what was “before” the universe was created?"

For the same reason you don't hear people asking "what were you doing before you were born" or "What's the difference between a ducks' legs".

"Simply, no so-called scientist seems to have challenged to define the outside of the big bang."

They have.

But to do so requires understanding advanced mathematics.

How much do you know about tensorial analyses and metrics?