“If the world wants you, it's gonna keep on coming till it gets you. And who am I that can fix it? Who am I that can change this if the world wants it so badly? Who am I to stop the end of the world if it keeps on coming?” -Patrick Ness

It's been a wonderful and diverse week over at the main Starts With A Bang blog on Medium, and we've covered an awful lot of ground if you missed anything (or want a re-read), including:

- Using up the Universe's Fuel (for Ask Ethan),

- LEGOs for those with a little Curiosity (for our Weekend Diversion),

- An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly, M59 (for Messier Monday),

- The Real Dangers of Mercury (as a Guest Post),

- The Greatest "Amateur" Astronomer of All Time, and

- The Truth About Asteroids (for Throwback Thursday).

As always, you've had plenty to say over here at the Starts With A Bang forum, and I'm pleased to share with you this edition of Comments of the Week! Let's dive right in.

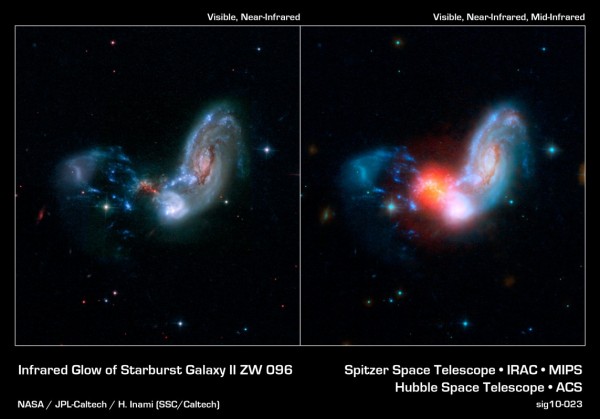

Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / STScI / H. Inami (SSC/Caltech), via http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/images/3430-sig10-023-A-Powerful-Shroude….

Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / STScI / H. Inami (SSC/Caltech), via http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/images/3430-sig10-023-A-Powerful-Shroude….

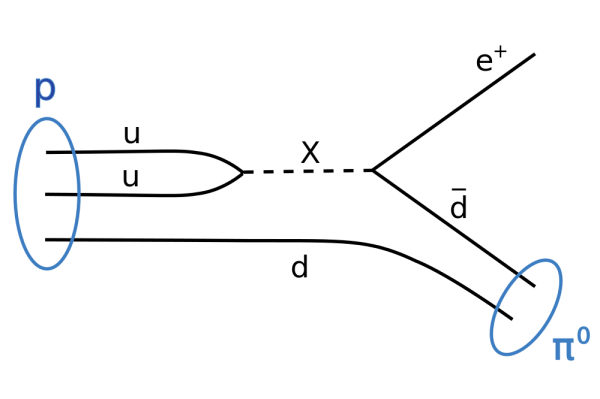

From DJ on the subject of using up the Universe's fuel: "By mass, I’m pretty sure most of the universe is dark matter, or dark energy if that counts. By atoms, it’s mostly hydrogen, but you’re not always careful with the distinction in your article. If proton decay exists, then there will be a time when all hydrogen disappears."

When we talk about the Universe's fuel, we are by definition talking about the normal matter that engages in nuclear fusion: bound states of quarks and gluons. Whatever dark matter is made of, we know it isn't those particles, and thus doesn't enter into the discussion. So however quarks and gluons are bound up in protons, neutrons and heavier nuclei is what we care about as far as this goes. Whether we look at this by counting the number of atomic nuclei or the mass fraction of atomic nuclei is going to determine what percentages we get out: if you have one iron atom and fifty free protons, that's a number ratio of 2%:98%, but a mass ratio of 53%/47%.

But I want you to be careful about your proton decay assumption.

In practically all models that admit proton decay (such as Grand Unified Theories), a free proton should eventually decay into a neutral-or-charged pion and either a positron or photons. But the timescales of this must be at least ~10^35 years, and that is for free protons. But most of the protons that exist in, say, our galaxy are bound to electrons, and are some 13.6 eV more stable than a free proton. You might not think that to be very much, but depending on the details of how (hypothetical) proton decay works, it could be enough to keep that system stable infinitely into the future, the same way helium-4 is stable even though it contains two neutrons. (Because although free neutrons decay, bound neutrons can be stable.)

From TM maybe on the same subject: "I have reason to believe that much of that early hydrogen is in room #317 of the Des Moines Holiday Inn."

This was the most baffling comment I got this week, but I tracked down that Holiday Inn here and believe I have identified the room in question.

Image credit: Des Moines Holiday Inn, via http://www.ihg.com/.

Image credit: Des Moines Holiday Inn, via http://www.ihg.com/.

This one's just going to have to await further research, I'm afraid. As a scientist, you should never be afraid to admit when something is just beyond your realm of expertise, and so I'm sorry to have to say "I just don't know" on this one. Anyone else know better?

From Venal S on The Real Dangers of Mercury: "[I] could not agree more with the quote. To[o] much of anything, good or bad can be harmful to us."

The quote in question was, “All things are poison and nothing is without poison; only the dose makes a thing not a poison.” The amazing thing is that the quote goes back to Paracelsus, the father of modern toxicology almost 500 years ago. The reason I find it amazing is that people still don't recognize that all things in small enough quantities are at worst benign and at best beneficial, and that those same things in excess can range from harmful to lethal. Some of them are more difficult to expel than others, of course, but when people -- even doctors and scientists -- rail against toxins in general, I too often feel that this is a super important nuance that gets lost in the shuffle. And on a more personal level, I feel that if people commonly understood this, my own city might have fluoridated drinking water. Alas.

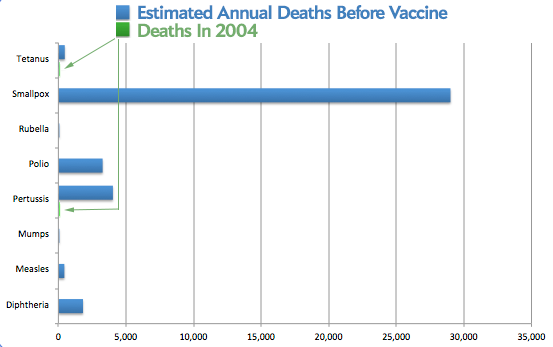

Image credit: Sandra W. Roush, Trudy V. Murphy, and the Vaccine-Preventable Disease Table Working Group / Journal of the American Medical Association.

Image credit: Sandra W. Roush, Trudy V. Murphy, and the Vaccine-Preventable Disease Table Working Group / Journal of the American Medical Association.

From LLD@14059437 on the same topic: "This article mentions that people need to educate themselves on scientific concepts. I agree with this concept and I believe that the issue of scientific misconceptions can easily be achieved in a democratic developed nation. But what about developing nations? Or nations with information censorship? Scientific information needs to be provided to people in these nations who do not have access to the internet or any other source of scientific information. Many of the people in these nations do not have the opportunity to read an article like this."

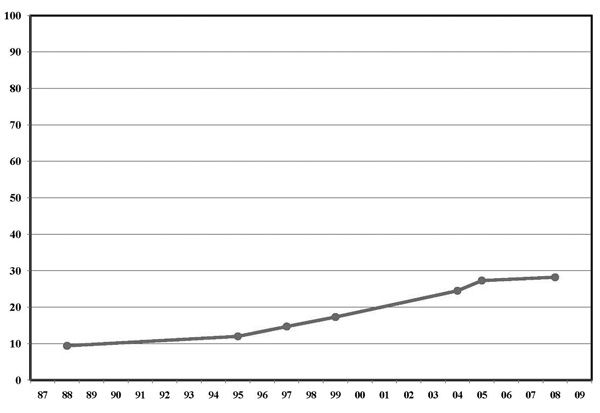

It's interesting to read a perspective like this from South Africa, because this article was written with the United States in mind: supposedly the paragon of democratic, developed nations, and yet the issue of scientific misconceptions has proven extremely difficult to clear up in this nation, as studies have continuously shown.

Image credit: Civic Scientific Literacy in the United States 1988-2008, Miller, Augenbraun, et al., 2006; Miller, 2010, via https://www.amacad.org/content/publications/pubContent.aspx?d=1093.

Image credit: Civic Scientific Literacy in the United States 1988-2008, Miller, Augenbraun, et al., 2006; Miller, 2010, via https://www.amacad.org/content/publications/pubContent.aspx?d=1093.

Fewer than one-in-three individuals can be considered scientifically literate, so even though the information is widely available, so is misinformation, and people seem to choose whatever information fits with their preconceptions, rather than using the valid information only to inform their decisions and viewpoints. And that's something that appears to be true regardless of where you go. (See some of the other comments, like this one or this particularly misinformative one.) So I agree that internet censorship and lack of internet access altogether are very large obstacles and detriments to scientific literacy, but even overcoming those obstacles doesn't seem to get us there.

From JM on the Greatest "Amateur" Astronomer: "Did not know about Mr. Roberts either. However, sad that the picture attached to his greatest advancement is of a Questar telescope, WITHOUT the optional piggyback camera mount accessory. Also, as I happen to have that same telescope, and also the piggyback mount, it’s one of the worst examples of piggyback astrophotography, as the telescope’s mount has not been designed for the additional weight of a camera. Attaching a camera there throws the whole thing out of balance, and that makes the concept quite bad."

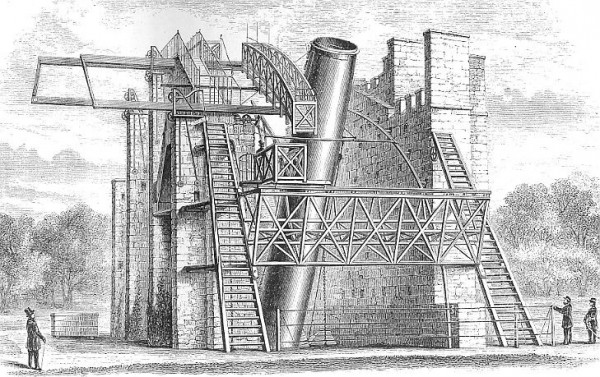

You know, it's always a little crushing when I realize that I've screwed something up, especially when it's something that I used to not know, then learned properly, and finally presented with the old, incorrect thought process behind it. (Surely I'm not the only one who's done that!) Let's get it right now: the telescope above -- the Leviathan of Parsonstown -- could be maneuvered up and down (altitude-adjustable) only, meaning it's not capable of pointing at all objects in the sky. If it were capable of being swiveled azimuthally, however, to all the directions a compass can point, then it could cover the whole sky. That's what an alt-azimuth mount does.

Image credit: © 2014 Rother Valley Optics Ltd., via http://www.rothervalleyoptics.co.uk/skywatcher-skyliner-400p-flex-tube-….

Image credit: © 2014 Rother Valley Optics Ltd., via http://www.rothervalleyoptics.co.uk/skywatcher-skyliner-400p-flex-tube-….

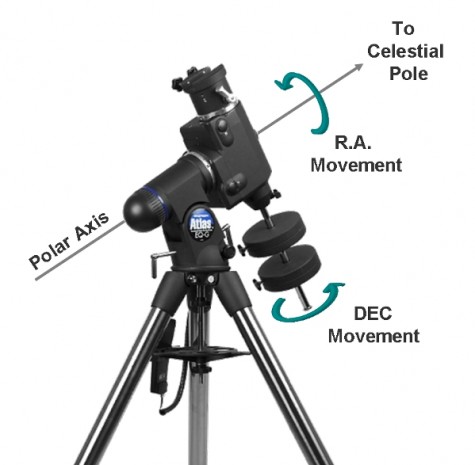

The problem with a mount like this is that it's very difficult to continuously point a telescope like this at a single object as the sky rotates; both the altitude and the azimuthal parts need to move simultaneously and at varying rates over the course of the night to track a single object. An equatorial mount, on the other hand, is designed so that the mount is always oriented with respect to the North (or South) Celestial Pole, such that it can rotate uniformly about one axis only throughout the night, tracking a single object so long as it's aligned properly.

This is the type of mount I should have illustrated. Interestingly enough, the largest telescopes in use today professionally use an alt-azimuth style instead of an equatorial style, because they're so heavy that the advanced computer tracking-and-pointing technology required to aim and point a mirror on an alt-azimuth mount is significantly cheaper than the materials necessary to build a stable equatorial mount for such a large thing. Interesting stuff!

And finally, by Roy Fields on the Truth about Asteroids: "If I have a one-in-70,000,000 chance of be killed by an asteroid strike in any given year, and there are 7 billion people on the planet, does that mean that hundreds of people should be killed by asteroids every year?"

Odds that are heavily weighted like this are among the most difficult for humans to intuit. We get a planet-killer asteroid -- the kind that wiped out the dinosaurs -- once every few hundred million years; the largest events are the most destructive but also the most unlikely. Your "one-in-70,000,000" chances of death factor these catastrophes in very heavily. If we get hit by the Earth-killer this year, all 7 billion of us go down, game over.

But what if we don't?

Image credit: The Day, via http://theday.co.uk/science/astronauts-warn-of-city-killer-asteroids.

Image credit: The Day, via http://theday.co.uk/science/astronauts-warn-of-city-killer-asteroids.

You might instead want to look at conditional probability: what are your chances of dying if the Earth-killer doesn't hit this year? It's much lower: somewhere around half those odds. City-killers are much more frequent, but much less destructive. They might take out a million people once every ten-to-hundred thousand years (when we get unlucky with their location), but much fewer during most strikes, which probably occur only every few hundred years. There are asteroids in-between city-killers and planet-killers, but those probably hit once every hundred thousand-to-a million years as well. So on average there are probably 100 people (assuming our world's population remains level at 7 billion indefinitely into the future) who'll die every year from asteroid strikes, but that's going to be heavily skewed towards years where there's a city-killer or larger asteroid hitting the Earth.

Image credit: Dr. Paul of http://dpquizlive.co.uk/2010/09/so-close-to-glory/.

Image credit: Dr. Paul of http://dpquizlive.co.uk/2010/09/so-close-to-glory/.

On average, you win something like $0.90 every time you play the lottery, too, but the vast majority of the time you don't win anything. Most years, no one dies of asteroid strikes, and in the years where someone does die, it's going to be far fewer than 100 people who do. In all of recorded human history, only one person ever has been hit by an asteroid: Ann Hodges of Alabama in 1954. Thanks to the power of the internet, this is her!

But when the wrong year comes along, lots more than 100 people will die, and over long enough timescales, that will average out to about 0.0000014% of the world's population dying of an asteroid strike every year.

And that's all for this week's Comments of the Week! Thanks for weighing in, and I'll see you back here next week for more!

Much to nitpick here:

- The K-Pg impactor wasn't a planet-killer, nor did it wipe out the dinosaurs.

To address the latter claim first, the impactor killed off the non-avian dinosaurs. But birds are twice as successful as mammals, measured as number of species.

To start to threaten the biosphere, the impactor needs to be 300 km according to Abramov's et al latest paper. Such an impactor can vaporize the oceans temporarily, so bacteria can only survive in the crust. They have revised their estimates of the late bombardment, so 1 such impactor may or may not have hit the Earth after the Moon-forming impact. It is hard to say, since early life likely had permeated the crust, being thermophile and autotroph.

To heat the crust with over 100 degC and kill off all life, you need a 500 km impactor IIRC. The K-Pg was 10 km.

- The only impactor that is known to have killed species is the K-Pg impactor. It could only do so because it hit a mature biosphere with life that laid down waste as sediments, the calciferous and sulfurous layers that tipped the biosphere into extinction mode.

- The average lifetime of a mammal species is 1 Myr. H. erectus had an amazing run of 2 Myr, but it is unlikely we will last that long since we are many more and so evolve much faster. (More efficient selection, can fixate alleles with smaller positive and negative fitness differences. At least the frequency and size of selective sweeps in humans have measurably increased as the population has, see John Hawk's blog.)

I don't know if it makes any sense to contemplate the dwindling supply of 10 km impactors that Jupiter throws our way. If they hit once every 100 Myr (roughly your "one-in-70,000,000 chance of be killed by an asteroid strike in any given year"), they will kill ~ 5 000/1 000 000 mammal species (say, 50 % of the ~ 10 000 existing at any given time, at a 1 Myr turnover), or ~ 0.5 % of species.

It is small odds an impactor will affect humanity, even considering those city-killers.

I should add that the K-Pg made a bull-eye in those waste sediments. They aren't continuous at all, so the biosphere was unlucky at that. Using that impactor for extracting an extinction rate will vastly over-estimate the risk.

To wit, if the harmful sediments cover 10 % of Earth surface, the 0.5 % threat will go down to 0.05 %.

Hi Ethan, you referred to two misinformative comments in the mercury thread but those comments are uncontested and hence the misinformation stands. Could you or Ms Stone perhaps counter those comments so that readers are put on the right track please?

Mother nature can be friendly and cruel at the same time. It is amazing how the very things that were meant to improve the standard of mankind can in turn harm it's existence. It is of great importance to have such insight about the world we live in.

I believe your non-answer to the non-question concerning the Des Moines Holiday Inn is just about the funniest thing I have seen all day and in fact for most days of my life. Rest assured it has not hit the top 100 in my life but still... It is you doing simple research. The arrows and bull's eye killed me.