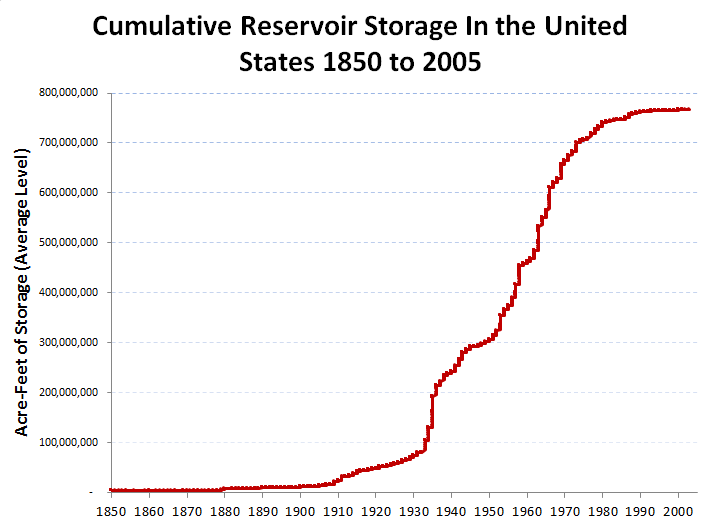

In the 20th century, water policy seemed easy: figure out another source of water to satisfy some projected demand, and find the money to build it. The money was almost always federal “pork barrel” funding for big water projects, or occasionally state bond financing. The vast number of dams built in the United States (see the figure) is an indication of how extensively this approach was used. But the leveling off of the curve below also shows that traditional dam construction can no longer be considered the only solution to our water problems. Moreover, most major water projects were designed and built with little or no consideration of the ecological implications for rivers, fisheries, wetlands, or migratory waterfowl. Water policy makers of the time either didn't understand what these impacts would be, or they didn't care.

Total volume of water that can be stored behind US dams over the past century. (Source: PH Gleick; USGS National Atlas data)

Total volume of water that can be stored behind US dams over the past century. (Source: PH Gleick; USGS National Atlas data)

The days of easy water and easy money and environmental ignorance are over. And that means that tackling water problems is more complicated. For many years it has become increasingly obvious that only a comprehensive integration of ecosystem protection, innovative supply sources, comprehensive water efficiency programs, smart economics and pricing, and good management will produce sustainable water systems.

Yet the old strategies and mindsets still linger in the minds of some politicians and water managers. A case in point is California, where it has long been clear that the massive water infrastructure built to store water in wet seasons for use in dry seasons, and to move water from the mountains and northern watersheds to the drier southern agricultural lands and cities, has caused massive ecological devastation -- not just the water supply benefits expected when the projects were funded.

For decades there have been discussions, studies, reports, commissions, meetings, plans, and arguments about how to fix California’s water problems – a veritable alphabet soup of acronyms litter the water policy landscape: CALFED, BDCP, DSC, CVP, SWP, CWC, CCWA, SWRCB

In the end, however, the idea of just building our way out of the problem, without fully understanding the implications of new construction for the things we really care about (water system reliability, resilience in the face of changing climate, ecosystem health and restoration) is just too easy for policymakers. As a result, we still get serious proposals for massive infrastructure costing billions without actually knowing if it will achieve our goals or just end up kicking the (gold-plated) can down the road to the next generation.

The Bay Delta Conservation Plan, especially the proposal to spend upwards of $25 billion (or likely more) to build a massive water diversion tunnel, is such a question mark. We are being asked to support it without the information necessary to really understand it. I recently described this lack of transparency and information in a Sacramento Bee opinion piece (available here).

The bottom line is that no multibillion dollar water project, or frankly any large project, should be authorized without a clear comprehensive understanding of its full costs and benefits, its operating rules, explicit detail on who is going to pay for it, details on the institutional structure in which it will operate, and a complete analysis of alternatives that might accomplish the same objectives. None of these are available for the Delta tunnels yet. Sustainable and successful water systems are possible to design and build, but it is going to require more effort to move away from old paradigms and thinking.